Oral and Dental Health

Oral and Dental Health

Publication date

This chapter was published in October 2022 and is due to be reviewed by October 2024.

Executive summary

This Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) outlines what we know about the oral health of residents in Surrey, their health outcomes and their access to dental services before and after the Covid pandemic.

Oral and dental diseases are widely prevalent, and whilst oral health has improved in recent decades, most people are at risk of developing some oral disease during their lifetime. The most common diseases are tooth decay and gum disease and the most serious is oral cancer.

Oral diseases affect quality of life causing pain, impacting days lost from work and school, and adversely affects people’s quality of life.

Certain groups are likely to suffer poorer oral health, and/or have increased challenges accessing dental services. These groups include:

- Children who are looked after

- Children who live in deprived areas

- Older adults in care homes

- People in prison

- People within gypsy Roma traveller communities

- People with learning disabilities

- People with multiple disadvantages (such as homelessness, substance misuse and mental health issues)

- People with Severe Mental Illness

- Recent migrants, particularly refugees

Oral health improvement for these groups requires a system-wide approach in terms of support in maintaining their own oral health, in addition to support in accessing dental services. Integrated Care Systems are becoming increasingly important in the commissioning of dental services.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected oral health in the general population and there is evidence that the pandemic has widened previous oral health inequalities. Wherever possible, the commissioning of dental services should be prioritised in more deprived areas.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Contents

- Introduction

- What are the causes of oral diseases and who is most likely to be affected?

- What do we know about our population?

- What are the key inequalities, unmet needs, and service gaps?

- National and local guidance and strategies (best practice)

- Key contacts

- Footnotes

- References

Introduction

Oral health is essential to general health and well-being and greatly influences quality of life. It is defined as a state of being free from mouth and facial pain, oral diseases and disorders that limit an individual’s capacity in biting, chewing, smiling, speaking and psychosocial well-being.[1]

Notes on dental and oral health data

- Dental and oral health data is often only available at Local Authority or larger healthcare boundary geographies.

- Timeframes for updates to dental data can differ between geographies as some surveys are locally commissioned.

- This chapter contains the most recent data (as of May 2022) at the smallest geographical areas available.

- Some dental and oral health data requires interpretation by specialists such as Regional Consultants in Dental Public Health and this also limits the availability of data.

- Dental decay in particular is so strongly linked to deprivation that deprivation data is generally the most appropriate to use for planning dental services and oral health interventions.

- There is no routinely collected data on the oral health of specific groups with generally poorer oral health such as homeless people and Gypsy Roma Travellers – often the views of people who support these groups can be useful in developing a more detailed local picture of need.

What are the causes of oral diseases and who is most likely to be affected?

Tooth decay

Tooth decay remains the leading reason for hospitals admissions among 5 to 9 year olds in England [2]. Tooth decay and gum disease are two of the most common diseases in the world in adults. Tooth decay doesn’t occur in people who don’t consume sugar and reducing both the amount and frequency of sugar consumed reduces the risk.

Gum disease

Gum disease is caused by bacteria in plaque gradually destroying the gums and bones around teeth leading to tooth loss. People who smoke are far more likely to suffer from gum disease.

People who brush twice a day with a fluoride toothpaste are less likely to suffer from tooth decay or gum disease.

Oral Cancer

Research suggests that more than 60 out of 100 (more than 60%) of mouth and throat cancers in the UK are caused by smoking and around 30 out of 100 (30%) are caused by drinking alcohol[3]. The combination of smoking and alcohol use increases the risk of oral cancer further, and poor diet is another risk factor.

The recommended time between dental ‘check-ups’ is between 3 months and 2 years depending on risk factors for oral disease[4]. Dentists check for early signs of decay, gum disease, oral cancer and other abnormalities so people who don’t attend often have more severe disease.

Children

Children who live in deprived areas are far more likely to suffer from tooth decay than children in less deprived areas. This is mainly due to differences in sugar consumption, tooth-brushing habits, and dental attendance.

In addition to pain, toothache can cause children to stop eating and sleeping, and reduces concentration and/or school attendance. All these effects can increase existing inequalities between children in the most and least deprived areas.

Older people

Older people are far more likely to have lost teeth due to gum disease and dental decay. This is because gum disease increases with age, and fluoride (which protects teeth from decay) only became widely used in the UK in the 1970’s.

The oral health of people in care homes was the subject of a national Care Quality Commission (CQC) report, Smiling matters: Oral health care in care homes[1].

Older people in care homes are particularly at risk of oral pain and disease because:

- People needing residential care are often less able to brush their teeth effectively and there is variation in how well care staff provide toothbrushing.

- People in care homes often increase the frequency and amount of sugar in their diet, and tooth loss/pain can make it more difficult to eat nutritious food.

- Access to dental services for people in care homes is highly variable, and dentists are limited in the amount of dental surgery (extractions etc.) they can provide outside of CQC regulated practices.

The influence of ethnicity on oral health

People from non-White groups have poorer oral health overall than people in White groups. However, deprivation is the key factor for poor oral health and people in non-White groups are more likely to live in more deprived areas.

In contrast with most health inequalities, when the effects of deprivation are removed, people from non-White groups in England were found to have better oral health than people in White groups. The differences could be partially explained by reported differences in dietary sugar[5].

Other priority groups

People with Severe Mental Illness are estimated to be 2.8 times more likely to have lost all their teeth compared with the general community[6].

National and international research, summarised by the UK Health Security Agency[7], shows that people with learning disabilities have poorer oral health and more problems in accessing dental services than people in the general population. People with learning disabilities may often be unaware of dental problems and may be reliant on their carers/paid supporters for oral care and initiating dental visits. Supporters are often inadequately trained for this and may not see oral care as a priority

Evidence consistently shows that people with learning disabilities have:

- higher levels of gum disease

- greater gingival inflammation

- higher numbers of missing teeth

- increased rates of toothlessness

- higher plaque levels

- greater unmet oral health needs

- poorer access to dental services and less preventative dentistry.

People in prison are likely to have worse oral health yet have less experience of using dental services prior to sentence.[8]

What do we know about our population?

Data on the proportion of children with dental decay is not regularly collected in Surrey.

Dental decay is the most common reason for 6-10 year olds to be admitted to hospital in England.

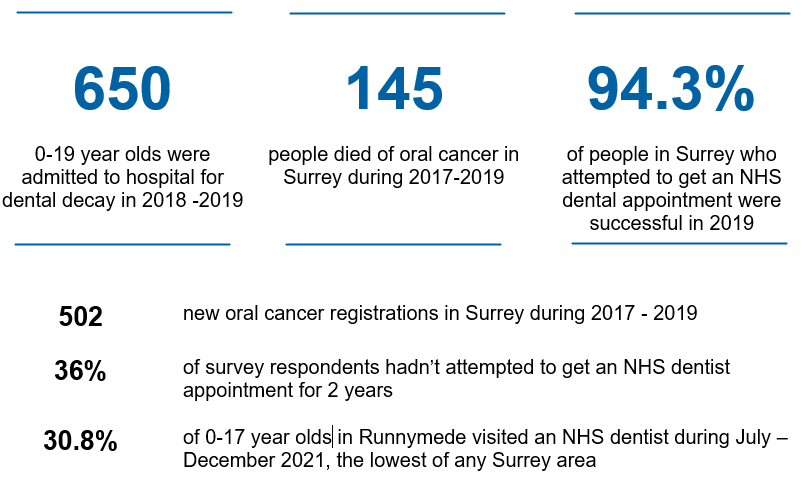

Data is collected on the number of children being admitted to hospital for dental decay (Table1). This gives an indication of the areas where severe decay is more common. The highest proportion of 6-10 year olds having dental extractions needing to be admitted to hospital for dental decay is in Spelthorne (0.9%), followed by Runnymede (0.7%) [2]. This is almost always for extractions of decayed teeth under General Anaesthetic. Waverley and Elmbridge had the lowest proportion (0.3%). The highest in England is Doncaster where 2.8% of all 0–19 year olds needed to be admitted to hospital for dental decay.

Table 1: Finished Consultant Episodes (single admissions to hospital) as % of Population with caries (decay) as the primary diagnosis), 2018/19

| LA Name | Age 0-5yrs | Age 6-10yrs | Age 11-14yrs | Age 15-19yrs | Total 0-19yrs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elmbridge | 0.1% | 0.3% | * | * | 0.2% |

| Epsom and Ewell | 0.2% | 0.4% | * | * | 0.2% |

| Guildford | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.1% | * | 0.2% |

| Mole Valley | 0.2% | 0.4% | * | * | 0.2% |

| Reigate and Banstead | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.1% | * | 0.2% |

| Runnymede | 0.3% | 0.7% | * | * | 0.3% |

| Spelthorne | 0.3% | 0.9% | 0.3% | * | 0.4% |

| Surrey Heath | 0.2% | 0.4% | * | * | 0.2% |

| Tandridge | 0.4% | 0.5% | * | * | 0.3% |

| Waverley | 0.1% | 0.3% | * | * | 0.1% |

| Woking | 0.3% | 0.5% | * | * | 0.2% |

Source: www.gov.uk/government/publications/hospital tooth extractions of 0 to 19 year olds (Calculated by PHE: National Dental Public Health Team from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)

Dental decay is strongly linked with deprivation, meaning we can use deprivation data to provide a localised indication of where there is increased dental decay in children. Many targeted oral health programmes in England are focussed on areas within the most deprived deprivation decile. Surrey does not have any localities within the most deprived decile.

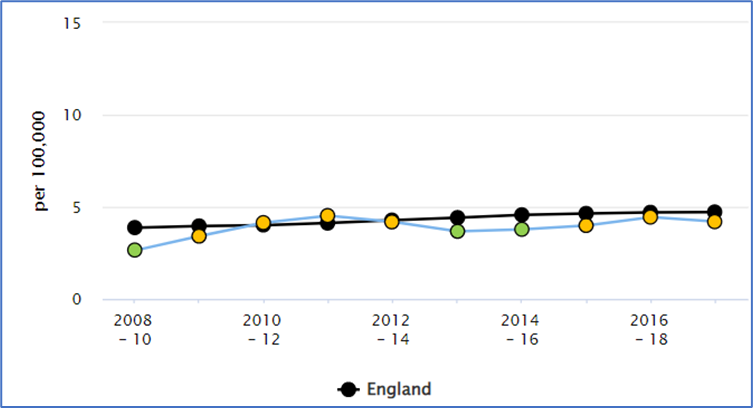

Oral cancer

Between 2017 and 2019 in Surrey, 4.2 people per 100,000 died of oral cancer. This is similar to the South-East rate (4.1) and England (4.7)[3]. See Table 3 below.

The actual numbers of people who died of oral cancer varies in Districts and Boroughs between 5 and 29 and the numbers are too small to make useful comparisons.

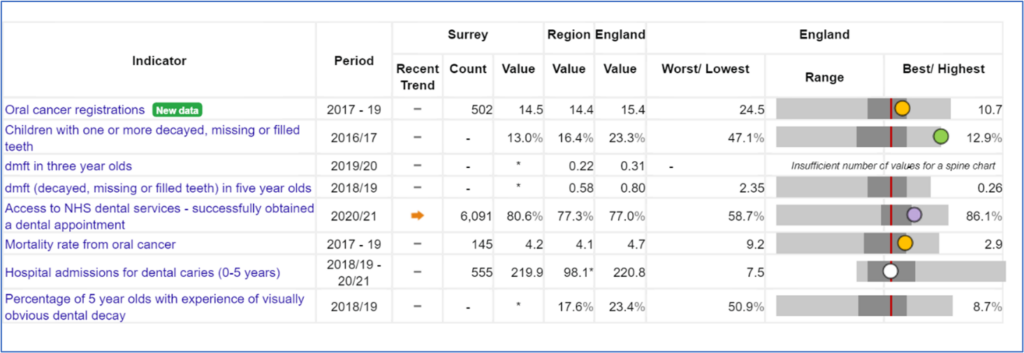

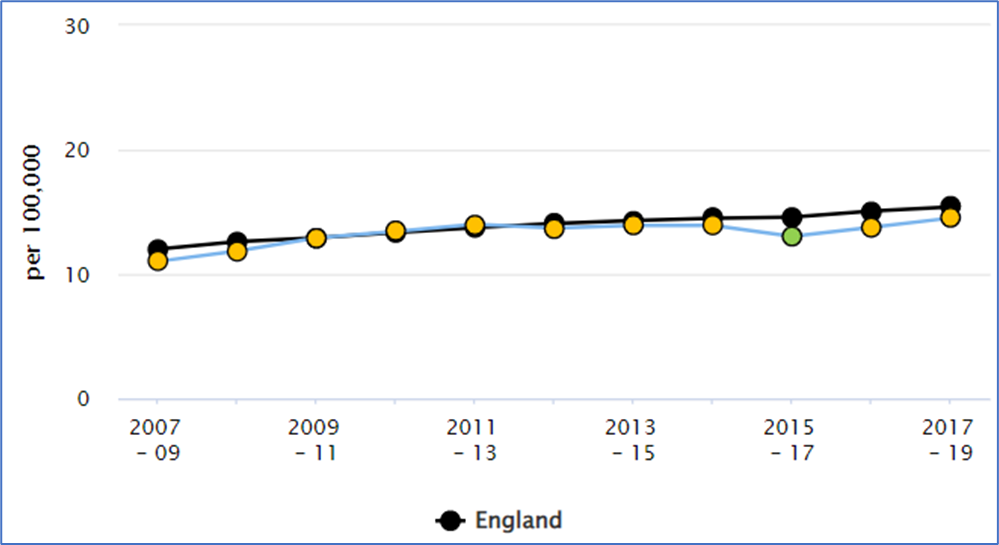

Table 2 below shows that for every 100,000 people in Surrey, 14.5 people were diagnosed(registered) with oral cancer between 2017 and 2019. This is similar to the South-East (14.1) and the England rate (15.4). The dental decay data (‘dmft’ – or ‘decayed, missing and filled teeth’) is not available in Surrey

Table 2: Fingertips Public Health Profile: Oral Health

Source: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/ (Calculated by OHID: Population Health Analysis (PHA) team from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Annual Death Registrations Extract and ONS Mid Year Population Estimates)

Table 3: Oral Cancer Deaths per 100,000 Population

| Period | Surrey | South East | England | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Value | 95% Lower CI | 95% Lower CI | |||

| 2008-10 | 80 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.9 |

| 2009-11 | 105 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 4.0 |

| 2010-12 | 131 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 4.0 |

| 2011-13 | 146 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 4.1 |

| 2012-14 | 137 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 4.3 |

| 2013-15 | 123 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4.4 |

| 2014-16 | 129 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| 2015-17 | 137 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 4.6 |

| 2016-18 | 153 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 4.7 |

| 2017-19 | 145 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 4.7 |

Source: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/ (Calculated by OHID: Population Health Analysis (PHA) team from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Annual Death Registrations Extract and ONS Mid Year Population Estimates)

Graph 1: Mortality Rate from Oral Cancer – Surrey v England

Source: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/ (Calculated by OHID: Population Health Analysis (PHA) team from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Annual Death Registrations Extract and ONS Mid Year Population Estimates)

Table 4: Oral Cancer Registrations per 100,000 Population

| Period | Surrey | South East | England | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Value | 95% Lower CI | 95% Lower CI | |||

| 2007-09 | 334 | 11.0 | 9.9 | 12.3 | 11.4 | 12.0 |

| 2008-10 | 367 | 11.9 | 10.7 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 12.6 |

| 2009-11 | 405 | 12.9 | 11.7 | 14.2 | 12.3 | 12.9 |

| 2010-12 | 425 | 13.4 | 12.2 | 14.8 | 12.6 | 13.3 |

| 2011-13 | 445 | 14.0 | 12.7 | 15.4 | 12.9 | 13.7 |

| 2012-14 | 445 | 13.7 | 12.5 | 15.0 | 13.1 | 14.1 |

| 2013-15 | 456 | 13.9 | 12.7 | 14.2 | 13.2 | 14.3 |

| 2014-16 | 464 | 13.9 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 14.5 |

| 2015-17 | 437 | 13.0 | 11.8 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| 2016-18 | 469 | 13.7 | 12.5 | 15.1 | 14.1 | 15.0 |

| 2017-19 | 502 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 15.4 |

Source: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/ (Calculated by OHID: Population Health Analysis (PHA) team from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Annual Death Registrations Extract and ONS Mid Year Population Estimates)

Graph 2: Oral Cancer Registrations – Surrey v England

Source: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/ (Calculated by OHID: Population Health Analysis (PHA) team from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Annual Death Registrations Extract and ONS Mid Year Population Estimates)

Current activities and services

A number of organisations have responsibilities for actions and services needed to improve oral health:

- NHS commissioning bodies are responsible for NHS dental services – NHS England and NHS Improvement are working with Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in the South-East to delegate commissioning responsibilities of dental services to ICSs.

- Surrey County Council has responsibility for population level oral health improvement and surveillance.

- Other key partners are involved in improving oral health; for example, Health Visitors including oral health in key visits, care homes having responsibility for the oral health of their residents, and schools aiming to reduce sugar in food.

- Services which aim to support people in improving their diet or stopping smoking are also important in improving oral health.

- Ensuring all parts of the system work together to improve oral health is essential and Integrated Care Systems can play a key role in this.

NHS Dental Services in Surrey

You do not have to pay for NHS dental services if you are:

- Under 18, or under 19 and in full-time education.

- Pregnant or have had a baby in the last 12 months.

- Being treated in an NHS hospital and your treatment is carried out by the hospital dentist (but you may have to pay for any dentures or bridges).

- Receiving low-income benefits or are under 20 and a dependant of someone receiving low-income benefits.

All adults outside these groups pay a subsidised amount dependent on the type of treatment they have. The NHS provides any clinically necessary treatment needed to keep your mouth, teeth, and gums healthy and free of pain[9].

Data on who uses NHS dental services excludes the large numbers of people in Surrey who use private dental services.

Access to NHS dental services

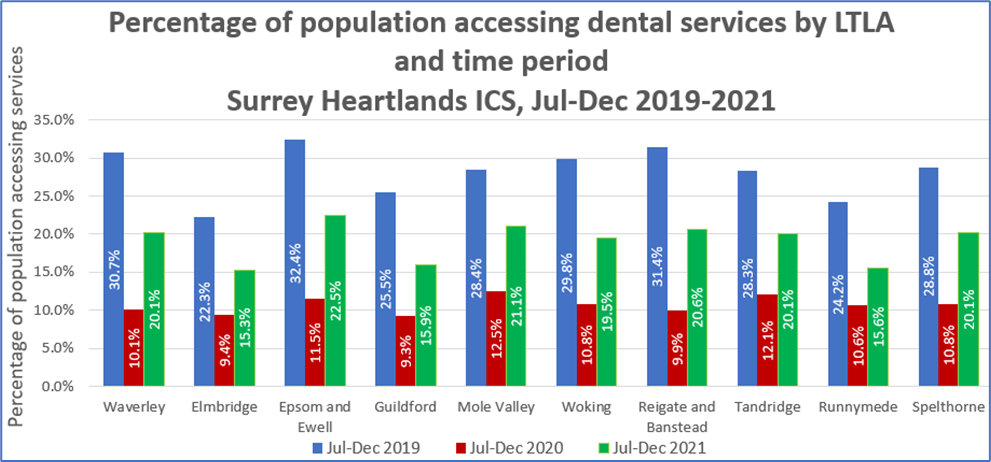

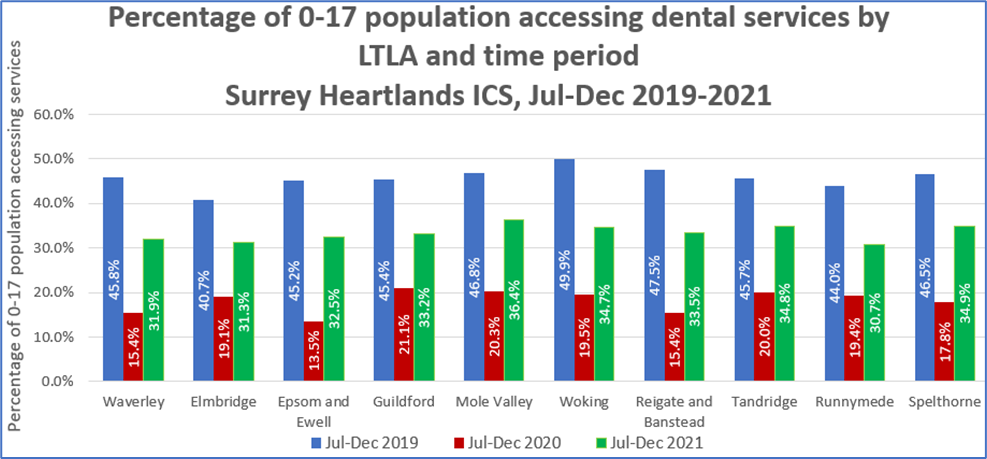

The most recent data pre-dating COVID-19 (Jul-Dec 2019) gives the percentage of adults and of 0-17s accessing NHS dental services in that period. Information on the 0-17s group is more useful as there are fewer 0-17s who chose to use private dental services. In Jul-Dec 2019, an average of 48.4% of 0–17 year olds in Surrey accessed NHS dental services. In Woking, 49.9% of 0-17s accessed NHS dental services in this period, but access was lower than the South East average in all other Surrey Districts and Boroughs. The lowest was in Mole Valley (40.3 %). The figure for Spelthorne, the most deprived area in Surrey, was 46.5% and this was the fourth highest figure in Surrey. The figures suggest that access to NHS dental services in Surrey was not a source of inequalities in this period in Surrey.

NHS dental practices were closed for face-to-face appointments for a significant period with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Following this, infection control procedures were in place until 2022 which drastically reduced the number of patients practices were able to see. The effects of this are likely to be observed for several years.

Comparing access to NHS dental services in Jul-Dec 21 with the same period for 2019 is useful in reviewing the ‘recovery’ of districts and boroughs in Surrey from the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of dental access:

- An average of 30.3% of 0-17s in the South East saw an NHS dentist in Jul-Dec 2021.

- In Surrey, the value was higher for all districts and boroughs in Surrey than the South East average.

- In Jul-Dec 19, Woking was the only area in Surrey with a higher figure than the South-East average.

In terms of inequalities:

- The highest percentage of 0-17s accessing NHS dental services in Jul-Dec 21 was in Surrey Heath (37.2 %).

- The lowest was in Runnymede (30.8%).

There is some evidence that recovery in terms of access to NHS dental services has been slower in the most deprived areas. This likely reflects differences in ‘health literacy’. Unlike GPs, anyone is free to choose where they see an NHS dentist. With limited access to NHS dental services, it is likely that people in less deprived areas have been more able to identify where appointments are available, and to travel further for appointments if needed.

Graph 3

Source: ONS mid-year population estimates (2019 and 2020) and Business Services Authority.

Notes: local authorities are arranged from least to most deprived (IMD).

Graph 4

Source: ONS mid-year population estimates (2019 and 2020) and Business Services Authority.

Notes: local authorities are arranged from least to most deprived (IMD).

The ‘GP patient survey’ is a questionnaire completed by patients who are registered with a NHS GP. The majority of surveys are completed via post or online.

As a baseline, 2019 was the last full year when access to NHS dental services was measured outside of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The GP Patient Survey showed that 94.3% of NHS GP patients in Surrey who attempted to get an NHS dental appointment were successful, similar to the England (94.2%) and South East (93.9) rates. Within Surrey the rate varied from 87.5% in NHS Thanet to 96.4% in NHS Ashford.

Results for the 2021 GP Patient survey show that in Surrey Heartlands, 36% of respondents had not tried to get an NHS dental appointment in the last two years (this excludes people who only use private medical care). Of the 36% who had not tried to get an appointment, 34% said they had not tried to access an NHS dentist because they prefer to see a private dentist.

Oral health improvement

There are two main approaches for local authorities and systems to improve oral health at the population level.

- Universal/population level approaches including ‘health in all policies and collaboration between partners.

- Targeted oral health promotion programmes which affect only the individuals in the target group.

Surrey has a population of 1.09 million people, spread across a large geography, with no areas in the top 5 or 10% of deprived areas in England. For this population, universal/population level approaches are often more appropriate.

Oral health included in ‘Health In all Policies’

Surrey County Council operates a ‘health in all policies’ approach and this includes oral health. Examples include:

- Inclusion of oral health in the health-related behaviours questionnaire for schools including pictorial version for schools for children with additional needs.

- Reducing sugar content in local authority commissioned services.

- Including dental health in healthy weight work to highlight the link between sugar consumption and dental decay.

Including oral health in the recommissioning of children’s services

Health visitors and other ‘early years’ professionals play an important part in the universal oral health improvement offer. Checks on toothbrushing and dental access are included in the service specification for health visitors.

Oral health is included in Surrey Children’s Community Health Services Needs Assessment: www.surreyi.gov.uk/dataset/2g4p0/surreys-childrens-community-health-services-needs-assessment

This will ensure oral health recommendations are reflected in early years commissioning and service provision. Oral health will also be included in the implementation of the ‘Helping Families Early Strategy’.

Pathways for vulnerable/priority groups

Certain groups are likely to suffer poorer oral health, and/or have increased challenges accessing dental services. Oral health improvement for these groups requires a system-wide approach in terms of support in maintaining their own oral health, in addition to support in accessing dental services:

- The issue of dental access for children who are looked after is a particular area of focus issue in Surrey, with collaboration between safeguarding leads, NHS commissioners, Public Health and clinical colleagues.

- The Surrey Adults Matter programme aims to improve the lives of people with multiple disadvantage (such as homelessness, substance misuse and mental health issues) and this includes supporting them in improving their general health and accessing healthcare services.

- The oral health of older adults in care homes is also an area of increasing focus – the Public Health team at Surrey County Council work with care homes on improving this.

What are the key inequalities, unmet needs, and service gaps?

There is no specific oral health data available for the groups outlined below. Much of the information comes from what is known nationally, and through engagement with local groups. The JSNA represents a high-level overview of the population, but it is important that the views of these groups are included when considering oral health improvement and commissioning of dental services.

People, particularly children, who live in more deprived areas represent the largest group for whom unmet needs exist. Needs include support in basic oral health needs, such as twice daily toothbrushing with a fluoride toothpaste and support in ensuring their diet is less damaging to oral health. This group also have the highest need for dental services but are often the least likely to access treatment and have regular, preventive dental appointments or ‘check-ups’. The oral health of this group should remain a focus of anyone with responsibility for oral health improvement and for access to dental services.

Many groups who would usually be classed as ‘vulnerable’ (for example due to learning and/or physical disability) are able to access specialist dental services through the Community Dental Service. However, acceptance criteria for these services mean that not all priority/vulnerable groups are eligible.

General Dental Services are the main point of access for dental services and anyone able to access these should be supported in this. The following groups may need additional support in accessing dental services:

- Improving dental access for children who are looked after is an opportunity for continued system-wide working. It can be very challenging for carers to find an NHS practice who is able to accept new patients. Improving dental access overall is a key priority for dental commissioners. However, there are opportunities for people working with looked after children and their carers to support them in accessing dental services.

- Dental access issues for people who are homeless, or who are experiencing severe and multiple disadvantages, have also been raised as a concern in Surrey. Oral health and access to dental services could be included specifically in Surrey Adults Matter and similar programmes. Again, general dental services are the most appropriate for this group, unless they are eligible for care with the Community Dental Service due to disability or other criteria. Access to dental services is not based on place of residence in the same way as GP services are organised. However, people who are homeless may need support in finding a dental practice and/or providing the necessary evidence for exemption of dental charges.

- People within gypsy Roma traveller communities also experience health and oral health inequalities[11]. Oral health inequalities in these communities have been identified as a particular issue in Surrey.

- The oral health of recent migrants, particularly refugees, is often raised as a concern. The concept of ‘trauma-informed care’ is important for people arriving in Surrey who may have experienced recent and/or severe trauma. Oral health is an important aspect of health and needs to be prioritised at the appropriate time. Provision of basic items such as toothbrushes and toothpaste is useful initially. Whilst access to dental services is also important, an oral examination is not common in all cultures, and can feel very intrusive, even without language and cultural barriers. Once urgent medical/dental needs are addressed, it may be more appropriate to incorporate routine dental appointments into a longer term, person-centred care pathway.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on oral health and access

Oral health inequalities

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected oral health in the general population and there is evidence that the pandemic has widened previous oral health inequalities:

Table 5: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on oral health inequalities[12]

| Effect of COVID-19 pandemic | Longer-term effect on oral health inequalities |

| Access to NHS dental services reduced for all but reuptake of services has been slowest in most deprived groups | Further progression of dental disease in the most deprived groups due to reduced early prevention/treatment |

| Early diagnosis of oral cancer reduced due to suspension of routine dentistry | Oral cancer is far more prevalent in more deprived areas so the effect will be greatest there |

| Cancellation of dental General Anaesthetic lists creating very lengthy backlog | Increased pain/missed schooldays in children in deprived areas as these are far more likely to require dental General Anaesthetic |

| Daily care for tooth-brushing etc. reduced | Increased decay/gum disease/pain in people who need help brushing their teeth |

| Sales of sugar, sweets, biscuits, and take-home soft drinks increased across all social classes | People in more deprived areas are far more likely to have dental decay |

| Sales of oral care products generally increased but there was a reduction in low/unwaged groups | Suggests widening existing inequalities in terms of decay and gum disease |

National and local guidance and strategies (best practice)

Access to dental services is important, particularly for identifying and treating disease. Integrated Care Systems are becoming increasingly important in the commissioning of dental services.

Maintaining oral health and avoiding disease is mainly achieved by a healthy, low-sugar diet and by toothbrushing.

There is an evidence-based toolkit providing the most recent guidance on how individuals can improve and maintain oral health:

The toolkit should be used whenever specific oral health guidance is needed. It includes information tailored to specific groups on:

- How and when to brush, including which types of toothpaste specific groups.

- Dietary advice for oral health – what should be included/excluded in an individual’s diet.

- Behaviour-change guidance for professionals to improve oral health including toothbrushing, diet, smoking and alcohol.

Anyone providing services for children should use the following national guidance: Child oral health: applying All Our Health – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Anyone providing services for adults in care homes should use the following national guidance:

A system-wide approach is important in implementing this NICE guidance. The national ‘Mouth Care Matters’ programme also has useful resources on improving the oral health of people in care homes – https://mouthcarematters.hee.nhs.uk/links-resources/

There is detailed information on how local authorities can improve the oral health of children and vulnerable adults in the toolkits below.

This reviews the evidence for various interventions and programmes in terms of effectiveness, cost-consideration, effects on inequalities, before giving an overall recommendation.

For example, it outlines targeted delivery of toothbrushes and toothpaste (e.g., by health visitors) as having ‘Some evidence of effectiveness’ with an ‘Encouraging’ effect on inequalities and being a ‘Good use of resources’. This is therefore ‘Recommended. Many of the studies on these interventions were carried out in areas with decay rates far higher than those seen in Surrey and this needs to be taken into account as the overall effects will be smaller in areas with less decay.

It also reviews the evidence for ‘One off dental health education by dental workforce targeting the general population’. There is ‘Evidence of ineffectiveness’ for this and this is not recommended.

There is detailed information on how local authorities can improve the oral health of vulnerably older people in the following toolkit:

This reviews the evidence of various programmes and interventions and makes recommendations for each. For example, programmes of training in oral health care for care staff/carers are rated as having ‘sufficient evidence of effectiveness’, with a ‘likely’ effect on inequalities and are ‘recommended. However, similar interventions for independently living older people are rated as having ‘inconclusive evidence’, with an ‘uncertain’ effect on inequalities and the recommendation is that these are viewed as ‘emerging evidence’.

Table 6: Opportunities for local authorities to improve oral health for vulnerable older people.

| Local Authorities | ||

| Service | Setting | Example |

| • social care • housing • population health • improvement • community and day services • oral health improvement |

• day care – healthy living • centres • community hubs • dementia cafes • wider initiatives, e.g. fire and rescue • home care district nurses • meals on wheels |

• training the wider workforce on oral health • consider supervised/supported tooth brushing schemes • advice and signposting information for public, patients and families-including touch points and voluntary sector • formal training for staff in supporting oral hygiene measures • the use of lay health workers to provide oral health advice • actions taken to limit sugar intake frequency where possible (and mitigate its impact where not) • oral health in daily personal care plan including oral health in joint strategic needs assessments (JSNA), and joint health and wellbeing strategies • including oral health standards, targets and guidance in public health policies and planning • creation of healthy environments conducive to good oral health through social and fiscal policies and community development |

Recommendations for consideration by other key organisations

Wherever possible, the commissioning of dental services should be prioritised in more deprived areas. It is also important for people in Surrey to have input into the commissioning of dental services. This could be:

- through Healthwatch Surrey.

- through forums such as the Surrey Partnership Forum.

- and ideally through more specific forums such as the Surrey Gypsy Traveller Communities Forum.

Early years settings in the most deprived areas of Surrey may want to consider local toothbrushing schemes. These can be linked to healthy eating and similar schemes. There are examples of awards schemes and similar which help settings give assurance for any locally driven toothbrushing schemes. Details are available from regional Consultants in Dental Public Health.

There are opportunities for Integrated Care Systems to work more closely on oral health and access to dental services, particularly for children and young people and for vulnerable adults. This could include:

- Including oral health and dental services in the ongoing implementation of the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy.

- Including oral health and dental services in system-wide work to support specific groups such as children in the most deprived areas, children who are looked after, adults who are homeless and older adults in care homes.

- Including oral health in broader, system-wide prevention strategies.

Key contacts

Lisa Andrews, Public Health Principal, [email protected]

Adam Letts, Public Health Lead, [email protected]

Author

Jonathan Lewney, Consultant in Public Health Surrey County Council, and Specialist in Dental Public Health.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20190624_smiling_matters_full_report.pdf

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hospital-tooth-extractions-of-0-to-19-year-olds

[3] https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/search/oral%20health#page/1/gid/1/pat/6/ati/402/are/E10000030/iid/1206/age/1/sex/4/cat/-1/ctp/-1/yrr/3/cid/4/tbm/1

References

[1] World Health Organisation. Oral health (online) [accessed 20 January 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/oral-health#tab=tab_1

[2] Royal College of Surgeons on England (online) [Accessed 21st January 2022]. Available from: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/news-and-events/media-centre/press-releases/dental-decay-hosp-admissions/

[3] https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/mouth-cancer/risks-causes

[4] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg19

[5] https://bmcoralhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12903-016-0228-6

[6] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0260766#pone.0260766.ref012

[7] Oral care and people with learning disabilities. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/oral-care-and-people-with-learning-disabilities/oral-care-and-people-with-learning-disabilities#oral-health-of-people-with-learning-disabilities

[8] http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/health-and-social-care-committee/prison-health/written/83238.html

[9] https://www.nhs.uk/nhs-services/dentists/what-dental-services-are-available-on-the-nhs/

[10] https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/search/dental#page/3/gid/1/pat/6/par/E12000008/ati/102/are/E06000036/iid/92785/age/1/sex/4/cat/-1/ctp/-1/yrr/1/cid/4/tbm/1