Screening

Screening

Publication date

This chapter was published in June 2023 and is due to be reviewed by June 2025.

Contents

- Glossary

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Cancer screening

- Non-cancer screening

- National and local strategies (best practice)

- Recommendations

- Related JSNA chapters

- References

- Name and contact details of authors

- Acknowledgements

Glossary

| AAA | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| AIS | Accessible Information Standard |

| ANNB | Antenatal and newborn |

| BCSP | Bowel cancer screening programme |

| BSP | Breast screening programme |

| CCG | Clinical Commissioning Group |

| CF | Cystic fibrosis |

| CHIS | Child health information system |

| CHT | Congenital hypothyroidism |

| CSP | Cervical screening programme |

| DESP | Diabetic eye screening programme |

| DS | Digital Surveillance |

| FASP | Fetal anomaly screening programme |

| FIT | Faecal Immunochemical Test |

| FOBt | Faecal Occult Blood test |

| GA1 | Glutaric aciduria type 1 |

| GOV.UK | UK Government website |

| GP | General Practice/Practitioner |

| HCU | Homocystinuria |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HNPCC | Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| HWBS | Surrey Health & Wellbeing Strategy |

| ICB | Integrated Care Board |

| ICS | Integrated Care System |

| IDPS | Infectious diseases in pregnancy screening |

| IVA | Isovaleric acidaemia |

| JSNA | Joint Strategic Needs Assessment |

| LBC | Liquid based cytology |

| LeDeR | Learning from lives and deaths – People with a learning disability and autistic people (LeDeR) programme |

| LS | Lynch syndrome |

| MCADD | Medium chain acyl dehydrogenase deficiency |

| MSUD | Maple syrup urine disease |

| NICE | The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NIPE | Newborn and infant physical examination |

| NBS | Newborn blood spot |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NHSE | National Health Service England |

| NHSP | Newborn hearing screening programme |

| NSC | National Screening Committee |

| PHE | Public Health England |

| PKU | Phenylketonuria |

| RDS | Routine Digital Screening |

| SCDP | Surrey Coalition of Disabled People |

| SCD | Sickle cell disease |

| SCID | Severe combined immunodeficiency |

| SCT | Sickle cell and thalassaemia |

| SLB | Slit Lamp Biomicroscopy |

| SSCA | Surrey and Sussex Cancer Alliance |

| SMS | Short message/messaging service |

| UK | United Kingdom |

Executive Summary

Screening is a way of finding out if people have a higher chance of having a health problem, so that early treatment can be offered, or information given to help them make informed decisions.

The NHS offers a range of screening tests to different sections of the population. The aim is to offer screening to the people who are most likely to benefit from it. For example, some screening tests are only offered to newborn babies, while others such as breast screening and abdominal aortic aneurysm screening are only offered to older people.

The link below takes you to a useful infographic summary timeline of all national screening programmes.

This JSNA chapter identifies the population need in relation to coverage and uptake rates of the national screening programmes across Surrey; describes the service in Surrey; identifies potential gaps, inequalities and offers a set of recommendations.

Population screening is offered to large numbers of people (usually based on their age or sex), who do not regard themselves as having the condition being screened for and who may not have sought medical advice. It is the responsibility of the organisation offering such tests and treatment, to make sure the programme operates at high quality to maximise benefit and minimise harm.

Screening programmes in Surrey are commissioned by NHS England, with operational and delivery support provided by a specialist Screening and Immunisation team, also within NHS England. Screening programmes across Surrey are delivered via a range of models and approaches including primary care, community providers and antenatal services.

The success of screening programmes in England are often measured through coverage and uptake rates, which are defined later for individual screening programmes.

Across Surrey, at time of writing (Spring 2023), the available performance data showed the following.

- Bowel screening uptake rates have steadily increased and surpass the national ‘acceptable’ and ‘achievable’ targets.

- Breast screening, coverage and uptake rates were just meeting ‘acceptable’ targets pre-pandemic but have since slipped below. ‘Achievable’ targets for both coverage and uptake have not been met however rates are improving following efforts to reduce backlogs due to the disruption of the programme during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Cervical screening coverage, for both age groups 25 – 49 years and 50 – 64 years, the ‘acceptable’ target has not been met. Coverage and uptake rates are generally better than those recorded for England. However, there is a need to work in partnership to improve the coverage and uptake of cervical cancer screening programmes locally.

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) programme is currently performing significantly lower than the ‘acceptable’ national target.

- Diabetic eye screening programme (DESP) uptake rates for Surrey were well above the ‘acceptable’ target level but failed to meet the ‘achievable’ target level, however rates are currently improving.

- Antenatal and newborn (ANNB) screening programme usually performs well above the national targets set for the six different elements.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on screening programmes across Surrey and the rest of the UK, including that screening programmes were paused for a period of time. Recovery work has been undertaken to return coverage and uptake rates back to pre-pandemic levels or higher.

This JSNA chapter has identified service gaps for people with learning disabilities and autism, people who are socio-economically deprived, certain ethnic groups, and trans people. The JSNA has identified the following service development opportunities to improve access to and uptake of screening programmes:

- Use insights to identify barriers to access particularly for specific population groups.

- Support General Practices (GP) to improve call/recall systems.

- Strengthen screening to treatment pathways.

There is a wealth of evidence to suggest that multidisciplinary and flexible approaches are effective in improving uptake of screening programmes. The screening inequalities strategy (GOV.UK, Oct 2020) provides ways to help increase screening uptake for those who might not be willing or able to access screening services. For example, evidence highlights the need to embed a whole systems approach to improving uptake and coverage, including improvements to data collection and targeting those most at risk of being unscreened. Improving uptake of screening programmes will require contribution and collaborative working by several stakeholders and organisations. The recommendations detailed in this chapter are intended to inform operational delivery of screening programmes and offer a strategic approach to improving uptake and reducing inequalities.

Introduction

Screening the population is a key prevention priority and is included in the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Screening is the process of identifying apparently healthy people who may have an increased risk of a disease or condition. Individuals can then be offered more information, further tests, or treatment as appropriate. A screening programme should only be recommended and provided if evidence shows the planned screening pathway, including further tests and treatment, will do more good than harm at reasonable cost (GOV.UK, Oct 2022).

Patients should be provided with information and support to enable them to make an informed decision on whether to participate in screening or not. Screening providers must make it as easy for disabled people to use health services as it is for people who are not disabled. This is called making reasonable adjustments. Reasonable adjustments can mean making sure screening clinics are held in accessible buildings. They can also mean changes to policies, procedures and staff training to make sure services work equally well for people with physical or sensory disabilities, learning disabilities or long-term conditions such as dementia.

The UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) advises Ministers and the NHS in the four UK countries (England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) about all aspects of screening policy and supports implementation. Using research evidence, pilot programmes and economic evaluation, it assesses the evidence for programmes against a set of internationally recognised criteria to ensure screening does more good than harm. This leads to screening programmes continuously evolving and in changes to eligibility criteria as the evidence base evolves. Each UK country sets its own screening policy based on the recommendations of the UK NSC. This means there can be some variation in the screening offered in each UK country. The NHS in each country is then responsible for the operational implementation and delivery of screening in line with UK NSC recommendations.

In England, the national screening programmes currently offered are :

- Cancer screening:

- Bowel cancer screening programme (BCSP)

- Breast screening programme (BSP)

- Cervical screening programme (CSP).

- Non-cancer screening:

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) programme

- Diabetic eye screening programme (DESP).

- Antenatal and newborn screening:

- Fetal anomaly screening programme (FASP)

- Infectious diseases in pregnancy screening (IDPS) programme

- Sickle cell and thalassaemia (SCT) screening programme

- Newborn and infant physical examination (NIPE) screening programme

- Newborn blood spot (NBS) screening programme

- Newborn hearing screening programme (NHSP).

This Screening JSNA chapter will focus on the England population screening programmes as listed above. For ease the chapter groups the different screening programmes into two groups as highlighted in bold text above (i.e. cancer screening and non-cancer screening). More detail on each of the screening programmes can be found at: Population screening programmes: detailed information – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) (GOV.UK, 2023).

Some other conditions are referred to in this chapter but are not discussed in detail as they do not form part of the national screening programme, even though a test may be available to help detect some of these conditions. Examples include, but are not limited to, lung cancer, prostate cancer, liver cancer and chlamydia screening. Information about a wide range of conditions, interventions or treatments can be found on the NHS website (NHS.UK, 2023).

Cancer screening can save lives by finding cancers at an early stage or by prevention or by identifying changes. Prevention and early detection are important to reduce deaths from cancer and include behaviour modification of risk factors (smoking, diet, exercise, and alcohol); increasing awareness of the early signs and symptoms of cancer; and encouraging participation in the national cancer screening programmes.

There are three cancer screening programmes offered in England: bowel, breast and cervical. These are free at the point of use and available to anyone in the target group, irrespective of risk profile, income, and disability. These screening programmes save lives, improve health, and enable choice (GOV.UK, Oct 2020). Every year across the UK around:

- 2,400 deaths are prevented by bowel cancer screening

- 1,300 deaths are prevented by breast screening

- 5,000 deaths are prevented by cervical screening.

This Screening JSNA chapter also looks at non-cancer screening programmes that are included on the national screening programmes. These screening programmes have been shown to reduce mortality, for example abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) usually cause no symptoms, but if the aneurysm ruptures it can be fatal. During the 2021/22 screening year across England, there were 39 AAA ruptures, 27 (69.2%) of which were fatal (GOV.UK, Feb 2023). AAA screening identifies abdominal aortic aneurysms early, enabling them to be monitored or surgically repaired which can reduce the rate of premature death by nearly 50%.

In 2019 there were over 3.3 million people diagnosed with diabetes mellitus in England (Diabetes UK, 2023a). Diabetic retinopathy is a complication of diabetes caused by high blood sugar levels damaging the back of the eye (retina). Diabetic retinopathy can be asymptomatic in the early stages, and over time can cause blindness if left undiagnosed and untreated. It is one of the most common causes of sight loss among people of a working age. Diabetic eye screening enables retinopathy to be promptly identified and treated, reducing the risk of sight problems or subsequent blindness.

In addition, there are several screening programmes offered in pregnancy (the antenatal period), and to newborn babies. The antenatal and newborn (ANNB) screening programme successfully identifies a range of conditions (if present) thus allowing timely interventions to be put in place where needed.

Cancer screening

Contents

- Who’s at risk and why

- Cancer prevalence

- Bowel cancer screening programme (BCSP)

- Breast screening programme (BSP)

- Cervical screening programme (CSP)

- Services in relation to need

- Local insights

- What are the unmet needs/service gaps?

- What are the key inequalities?

- What is this telling us?

Who’s at risk and why

Cancer is a term that is used to refer to a number of conditions where our body’s cells begin to grow and reproduce in an uncontrollable way. There are many different types of cancer. The most common cancers in the UK, based on new cases diagnosed in 2019 are: breast (n=56,987), prostate (n=55,068), lung (n=48,754), and bowel (n=44,706) (WCRF, 2023). It should be noted that figures reported from 2020 onwards should be treated with caution due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected cancer testing and diagnostic services.

Certain risk factors (including age, ethnicity, gender and deprivation) are known to increase the chance for one or more of our body’s cells becoming abnormal and leading to cancer.

Cancer mortality rates are highest in the most deprived areas. In 2020, the age-standardised mortality rates in the most deprived quintile of England were 53% higher for men and 55% higher for women than in the least deprived quintile. For the 2017 to 2019 period, the under-75 mortality rates from cancer in Manchester was 182 per 100,000 (worst) and in Westminster it was 87 per 100,000 (best). For Surrey it was 106 per 100,000, the ninth best in England (House of Commons Library, Feb 2023).

Although overall the mortality rates in Surrey compare well to England, cancers are the second largest contributor to the gap in life expectancy between people living in the most and least deprived quintiles in Surrey (further detail is available in The Surrey Context: People and Place | Surrey-i (surreyi.gov.uk)). Inequalities in cancer incidence in relation to socio-economic deprivation are one of the major concerns as it is known that risk factors for cancer, especially smoking, are strongly influenced by socio-economic determinants as well as factors such as access to care. The relationship between deprivation and cancer is complex and multifaceted.

Cancer prevalence

The rates of patients with cancer, as recorded on GP practice disease registers, have been increasing for the past five years. Data for 2021/22 shows that cancer prevalence in Surrey Heartlands was 3.9% (43,778 people) and in Frimley it was 3.1% (25,517 people). The rate in England was 3.3%. The rate of new cancer cases diagnosed in 2020/21 was 492.2 per 100,000 people in Surrey Heartlands and 434.8 per 100,000 people in Frimley. Surrey overall has a significantly lower mortality rate from all cancers combined (102 per 100,000) when compared England (125 per 100,000). The latest data for Surrey is available on Public health profiles – OHID (phe.org.uk) and shows that in 2021 the under-75 mortality rates from cancer in Surrey remains the ninth best in England with a rate of 98 per 100,000 compared with 122 per 100,000 in England.

Note: The data dashboards linked to this JSNA chapter can also be searched to find GP practice level data.

Bowel cancer screening programme (BCSP)

Historically the bowel cancer screening programme was offered every 2 years to men and women aged 60 to 74 years. In August 2018, ministers agreed to expand bowel cancer screening in England, with a roll out over time down to the age of 50. The NHS started to reduce the age range for bowel cancer screening from April 2021. In Surrey the cohort age range is being extended by reducing the age at which it starts, to include those aged 54 years from April 2023. This could influence uptake rates going forward. People older than 74 can ask for a screening kit every 2 years by calling the free helpline on 0800 707 60 60.

In addition, the ambition is that people with Lynch and Lynch-like syndrome will be included for surveillance in the bowel cancer screening programme in 2023/24. Lynch syndrome (LS) is a rare condition that can run in families. It used to be called hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. People affected by LS have a higher risk of developing some types of cancer. For more information visit: Lynch syndrome (LS) | Macmillan Cancer Support

Public information about bowel cancer screening is available on the NHS website and further information (including videos) can be found at: Bowel cancer screening: programme overview – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk). Members of the public can call the free bowel cancer screening helpline on 0800 707 60 60.

Bowel cancer screening data

The latest published full year data available for Surrey is 2022. The bowel cancer screening data presented below is from the years 2017/18 to 2021/22. The performance data discussed below is broken down by England, Surrey and Integrated Care Board (ICB) level. Data for 2017/18 to 2019/20 is available at place-based partnership level. Places covered below are: East Surrey, Guildford & Waverley, North West Surrey, Surrey Downs and Surrey Heath. Data from 2020/21 to 2021/22 is available at integrated care system (ICS) level, because these aligned with the old clinical commissioning group boundaries that existed at those times i.e. Surrey Heartlands, North East Hampshire and Farnham, and Frimley where appropriate.

NHS screening key performance indicators define bowel cancer screening coverage as: “The proportion of eligible people aged 60 to 74 who were screened (adequately participated in Faecal Occult Blood test (FOBt) bowel cancer screening) in the 30 month period. National ‘acceptable’ and ‘achievable’ target levels have yet to be set.”

Bowel cancer screening coverage rates (in the last 30 months) for those eligible across Surrey Heartlands ICB area has steadily increased from 60.4% in the year 2017/18 to 72.0% by 2021/22. Frimley ICB area rates have also steadily increased from 59.4% in the year 2017/18 to 71.9% by 2021/22. The average uptake rates across England have also improved from 59.5% in 2017/18 to 70.3% in 2021/22. The latest NHS quarterly data on coverage can be accessed at NHS population screening programmes: KPI reports 2022 to 2023 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) and show coverage rates continue to improve with rates for Surrey currently at 72.3% for Q1 2022/23, well above pre-pandemic levels.

Bowel cancer screening data at GP level can also be found by accessing the data dashboard.

NHS screening key performance indicators define bowel cancer screening uptake as: “The proportion of invited people who were screened (adequately participated in FOBt bowel cancer screening), within the invited screening episode, at time of reporting.”

Note: the FOBt test has now been replaced by the Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) in screening for signs of bowel cancer. FIT detects more positive results compared to FOBt and shows fewer false negatives. Also, FIT is a more acceptable test for participants because it is easy to take, has short sampling times and no food restrictions (Mousavinezhad et al, 2016).

All places across Surrey have performed above the “acceptable” target level of 52.0% and since the year 2018/19 all have performed above the “achievable” target level of 60.0%.

Bowel cancer screening uptake rates for those aged 60 to 74 years old across Surrey Heartlands ICB area has steadily increased from 57.9% in the year 2017/18 to 71.9% by 2020/21 with a slight reduction to 70.7% in year 2021/22. Frimley ICB area rates have also steadily increased from 56.5% in the year 2017/18 to 71.9% by 2020/21 with a reduction to 69.8% in year 2021/22. The average uptake rates across England also improved from 57.6% in 2017/18 to 70.7% in 2020/21, but also with a slight reduction to 69.6% in 2021/22. The latest quarterly data on uptake can be accessed at NHS population screening programmes: KPI reports 2022 to 2023 – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) and it should be noted that there was a sudden drop in uptake rates from 64.3% in quarter 3 to 54.6% in quarter 4 of 2019/20. This could be due in part, to the run up to and introduction of full lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Data isn’t available for quarter 1 of 2020/21, again due to the pandemic, though rates did improve to over 71% for the rest of the year. This improvement could be due to the efforts of cancer screening services to reduce backlogs created by the pandemic. It does appear that uptake rates have increased across Surrey to 86.5% for quarter 2 of 2022/23.

All place-based partnership areas within the ICBs in Surrey steadily increased uptake rates from 2017/18 to 2020/21 in line with the whole of Surrey. North East Hampshire and Farnham place consistently reported the highest uptake rates with 60.7% in 2017/18 increasing to 74.9% in 2020/21. North West Surrey recorded the lowest uptake rates locally with 55.0% in 2017/18 increasing to 62.9% in 2019/20.

Local NHS names and boundaries changed during 2020/21 and 2021/22, and in Surrey the data is only available at ICB level for these years. Bowel cancer screening uptake in 2020/21 for Surrey Heartlands and North East Hampshire and Farnham was 73.2% and 74.9% respectively. Uptake in 2021/22 for Surrey Heartlands and Frimley were 70.7% and 69.8% respectively.

Breast screening programme (BSP)

In England, breast screening is currently offered to women aged 50 years up to their 71st birthday. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the AgeX research trial looked at the effectiveness of offering some women one extra screen between the ages of 47 and 49, and one between the ages of 71 and 73. This trial stopped during the COVID-19 pandemic so an extra screen is no longer being offered to these age groups. The breast screening invitation pathway changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. People were sent a letter asking them to book an appointment rather than being sent a pre-booked appointment. This is now reverting as of Spring 2023 and people will be sent a letter with a pre-booked appointment with details of when and where to go. The impact of returning to pre-booked appointment letters on uptake rates is not yet known (as of May 2023).

Further information can be found at Breast screening: programme overview – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Breast cancer screening data

The latest full year data available is for 2022. The breast cancer screening data presented below is from the years 2017 to 2022 where available and represents performance for when the old CCGs were still in place. The performance data discussed below is broken down by England and Surrey local authority area.

NHS screening key performance indicators define breast cancer screening coverage as: “The proportion of women eligible for screening who have had a test with a recorded result at least once in the previous 3 years.”

Surrey performed above the “acceptable” target level of 70.0% but did not achieve the “achievable” target level of 80.0% before the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Due to COVID-19, the programme was paused for 3 months and there was a significant drop off in performance for the years 2021 and 2022.

Coverage rates of breast cancer screening for those eligible across Surrey remained fairly static between 75.1% in 2017 and 74.7% in 2020. Rates did reduce to 65.6% in 2021 and 65.3% in 2022. This was due to restrictions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and the challenges in offering the service. A similar pattern was seen across England.

Steady improvements have been made, due in part to the efforts of cancer screening services getting back on track, to help reduce backlogs created by the pandemic. The Surrey service are reporting that they have fully recovered post COVID-19. This should be confirmed once the national data is officially released.

NHS screening key performance indicators also define breast cancer screening uptake as: “The proportion of eligible women invited who attend for screening.”

In terms of breast cancer screening uptake, Surrey overall achieved or just surpassed the “acceptable” target level of 70.0% up to the year 2019/20. The “achievable” target level of 80.0% has not been met.

Breast cancer screening uptake rates for those eligible and offered across Surrey remained fairly static at 70.5% in 2017/18, 72.8% in 2018/19 and 71.6% in the year 2019/20. This was similar to the average uptake rates across England for the same period. Uptake rates reduced substantially in 2020/21 for both Surrey (60.5%) and England (62.3%). This overall reduction in uptake rates was due to the restrictions experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulties caused in delivering the breast screening service. Overall uptake rates continued to remain lower during 2021/22 for both Surrey (65.0%) and England (63.1%). The latest data on uptake rates is available on Public health profiles – OHID (phe.org.uk).

Cervical screening programme (CSP)

The NHS cervical screening programme in England is offered to people with a cervix aged 25 to 64 years. The first invitation is sent to eligible people at the age of 24.5 years. Samples are normally taken at a patient’s GP practice. Routine screening is offered every three years up to 49 years of age and every five years from 50 to 64 years of age. Depending on the result of the screen, people may be recalled earlier than these routine recall intervals.

Cervical screening looks for the human papillomavirus (HPV) which can cause abnormal cells on the cervix. If HPV is found a cytology test is used as a triage, to check for any abnormal cells.

Most HPV infections are transient, and slightly abnormal cells often go away on their own when the virus clears. If HPV persists, abnormal cells can, if left untreated, turn into cancer over time.

HPV is a very common virus which currently effects around 8 in 10 people. The HPV vaccination is offered to girls and boys aged 12 to 13 years (born after 1 September 2006) and could have a positive impact on current prevalence rates. However, this may have a negative impact in terms of people’s behaviour and not taking up the screening offer because they have previously been vaccinated. There has been a noticeable decline in uptake rates in the younger cohort who were vaccinated in the early rounds and are now eligible for cervical screening. There’s no treatment for HPV. Most HPV infections do not cause any problems and are cleared by the body’s immune system within 2 years. Treatment is needed if HPV causes problems like genital warts or changes to cells in the cervix.

Further information can be found at Cervical screening: programme overview – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

Cervical cancer screening data

There are two NHS key performance indicators for cervical cancer screening coverage which are defined as follows:

- “The proportion of women in the resident population eligible for cervical screening aged 25 to 49 years at end of period reported, who were screened adequately within the previous 3.5 years” and

- “The proportion of women in the resident population eligible for cervical screening aged 50 to 64 years at end of period reported, who were screened adequately within the previous 5.5 years.”

Cervical cancer screening coverage: aged 25 to 49 years old (Female, 25-49 yrs.)

The national programme has a performance threshold for cervical screening of 80% of the eligible population. The level achieved by Surrey Heartlands ICB, Frimley ICB and England has been less than 80.0% for a number of years. The latest full year data available is for 2021/22. In 2021/22, the proportion of eligible people screened in Surrey Heartlands ICB area was 71.0%, down from 75.4% in 2011/12. For Frimley ICB area, rates for 2021/22 were 70.6%, down from 73.8% in 2011/12. A similar picture is seen for England with rates reducing from 73.5% in 2011/12 to 68.6% in 2021/22.

Although the data shows slight increases in the percentage coverage between 2017/18 and 2019/20, statistically there has been no significant change in the trend of coverage since 2017/18 in both Surrey Heartlands ICB and NHS Frimley ICB, and for England as a whole.

Cervical cancer screening coverage: aged 50 to 64 years old (Female, 50-64 yrs.)

The national programme has a performance threshold of 80% of the eligible population. Between 2017/18 to 2021/22, the level achieved was less than 80.0% by Surrey Heartlands ICB, Frimley ICB and England.

In 2021/22, the proportion of eligible people screened in Surrey Heartlands ICB area was 75.0%, down from 79.9% in 2011/12. For Frimley ICB area, rates for 2021/22 were 76.9%, down from 80.5% in 2011/12. A similar picture is seen for England with rates reducing from 80.0% in 2011/12 to 75.0% in 2021/22.

There has been no significant change in the decreasing trend of coverage since 2017/18 in both Surrey Heartlands ICB and Frimley ICB, and for England as a whole.

Services in relation to need – cancer screening (bowel, breast, cervical)

| Screening programme | Service provided in Surrey |

| Bowel screening | Royal Surrey County Hospital – Bowel Screening Hub covers South East, South West and part of Midlands (Bucks & Milton Keynes) |

| Breast screening | ‘InHealth’ (IH), independent provider covering Surrey – service covers Surrey plus North East Hampshire |

| Cervical screening | Primary care (GP surgeries) |

| Colposcopy | Ashford and St Peters Hospitals – 2 hospital sites (ASPH is the ‘lead site’). Royal Surrey County Hospital Surrey and Sussex Hospitals – main hospital site is in East Surrey (Redhill). |

Local insights – cancer screening (bowel, breast, cervical) services

Feedback from members of the Surrey Coalition of Disabled People (SCDP)

In terms of bowel cancer screening, SCDP fed back about difficulties with collecting the sample, particularly if members had difficulties with their hands and keeping their balance. Members said that once the sample hits the plastic it can be very difficult to hold on to it. They also said there could be difficulties trying to get the sample from an elderly lady with dementia who didn’t understand why this had to be done.

Members said that using the sample brush was easier, but the example given in the accompanying literature was complicated. People didn’t know how much should be on the brush; they didn’t want too much but they also didn’t want to not have enough! One of their members with a visual impairment received the screening test through the post. She was fortunate because someone (don’t know who) called her to let her know the test kit was coming, which was a help. The person was able to arrange to send her some large print instructions, as she was not able to read the original ones that came with the kit.

Everyone who SCDP spoke to, said the screening programme needed to provide something harder/stronger to catch the sample in. A lady with a visual impairment had difficulty putting the sample into the envelope as the opening was very small and the instructions were not clear. Lastly, those who have a raised toilet seat find it even more difficult to collect the sample.

There was one member who found the whole thing not too bad, but this was because her husband is her carer and was able to help her with the test.

In terms of communication, they said there is still no SMS text number for ordering of bowel cancer screening kits and no SMS contact on letters (or Web), despite often being targeted at a senior cohort who are “70% aged 70 with a hearing loss”. They also said there is no easy way to discover provision of or ask for hearing loops, or BSL support at appointments and walk-in services, because neither the booking centre nor the venue has a non-telephonic contact. They could not find support for people who are visually impaired, such as a braille insert with the phone contact. Also, the offer of large print should be in large print.

Note: More information can be found at NHS bowel cancer screening: helping you decide – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk), however this does not include advice specifically for people with visual impairments. People with hearing or speech difficulties can use the Relay UK service to contact the NHS. Dial 18001 then 0800 707 60 60 from a textphone or the Relay UK app. There is also a free helpline on 0800 707 60 60.

Feedback from Healthwatch Surrey

Carers for people with mental health conditions have shared that assessments and early diagnoses for cancer can be very difficult and traumatic. During this time, people can avoid asking for help or support and can find this an isolating experience.

We have heard from unpaid carers, supporting their loved ones during the early stages of dementia diagnosis, highlighting how such conditions impact capacity across all aspects of life. In one such example we heard how an individual had developed unhealthy eating to cope with the decline in their mental health, having an impact on their physical health. Also, their capacity to comprehend letters or other information sent to them by health services is impeded, leaving them reliant on the support from a family member or friend to help them.

We have heard from young people with mental health issues seeking help for cancer related concerns, however due to the sensitivity of these issues, they can find the situation difficult and medical professionals are not always sensitive to this.

Regular communications to patients about attending screening appointments were disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and in one case a patient proactively seeking help was diagnosed with cancer.

We have heard from a resident with a degenerative condition and a learning disability, who has been unable to access a cervical screening due to her GP practice not being able to accommodate screenings for wheelchair users.

We have heard from a community leader from the Nigerian community in east Surrey who has raised concerns that men in her community do not respond to requests to attend screening. We have also heard that people from some cultural backgrounds refuse to register with GPs and therefore won’t receive invites for screening.

What are the unmet needs / service gaps? – cancer screening (bowel, breast, cervical) services

For people who are trans it is important to ensure that GP records are up to date and accurate (including whether assigned male or female at birth) so that they are invited for screening correctly (GOV.UK, Jan 2023).

In terms of breast screening, there are inequalities in the prison population, primary care engagement, accessible screening locations, and identification of those with special characteristics.

Programmes did not produce annual reports, undertake their usual patient feedback activities or produce improvement plans during the COVID-19 pandemic. This limits recent data and related analysis of unmet needs and service gaps.

In response to the low uptake of screening in people with learning disabilities and autistic people, the LeDeR report 2020/21 recommends the following:

- As there is limited resource within screening to address health inequalities, consideration should be given to the appointment of a health inequalities specific screening professional.

- National data cannot be broken down to identify uptake in people with learning disabilities and/or autism, therefore routine local reports are required to monitor health inequalities in people at high risk of facing health inequalities.

- Further work is required to improve communication between systems used by GPs / screening providers

- Routine easy read invite letters and information should be available to anyone who may require this but specifically everyone with a learning disability.

- Annual health checks should be used as an opportunity to review screening uptake.

- Further work is required to engage people with learning disabilities and obtain routine feedback.

- Each screening service should undertake a self-assessment to review their services accessibility for people with learning disabilities and autistic people.

- Consideration should be given to the development of pathways for people with learning disabilities and autism to access each of the screening programmes, including addressing service gaps above and an alternative pathway for people with learning disabilities who do not attend appointments.

- Monitoring the uptake of the Oliver McGowan training across screening programmes within Surrey Heartlands.

- Improved monitoring of compliance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Evidence shows that the rate of cancer screening uptake by people with a learning disability is lower than for the general public. A report by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) showed that in the previous five years, the proportion of women aged 50 to 69 years with a learning disability who received breast cancer screening was 51%. This compares to 65% of women in the same age group without a learning disability. NICE also recommends that other routine healthcare such as cancer screening form an important element of the annual health checks. The NICE guideline on care and support of people growing older with learning disabilities recommends that older people with a learning disability should be offered the same routine screening as older people without a learning disability.

A report was commissioned covering the Surrey Heartlands area in 2021/22 to support the ICS efforts in reducing the inequalities faced by people with learning disabilities, particularly the mortality gap, and to inform strategic prioritisation of these efforts. The report found that people with learning disability in Surrey are significantly less likely than people without learning disability to receive cancer screenings. Also fewer people with learning disability in Surrey died from cancer than expected in 2021/22, given the degree of inequality in cancer screening rates between people with and without learning disability.

Greater detail on this and other inequality issues faced by People with a Learning Disability can be found in the People with Learning Disabilities chapter of the Surrey JSNA.

What are the key inequalities? – cancer screening (bowel, breast, cervical) services

Cancer is one of the biggest contributors to inequalities in life expectancy with people from the most deprived communities more likely to get cancer, be diagnosed at a late stage for certain types of cancer and to die from the disease.

Screening inequalities can manifest themselves at any point along the screening pathway. The pathway consists of:

- invitation and identification of eligible population

- provision of information about screening

- access to screening services

- access to treatment

- onward referral

- outcomes

Early presentation, referral, screening and diagnosis are key to addressing the inequalities in life expectancy and the national NHS England ‘Core20PLUS5’ approach to reducing healthcare inequalities identifies cancer as one five focus clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement. It sets an ambition for 75% of cancers to be diagnosed at stage one or two by 2028.

Local and national interventions to drive early diagnosis have the opportunity to help address these inequalities. The Core 20 Plus Accelerator Sites is a new NHS England programme delivered in partnership with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the Health Foundation. It is made up of seven accelerator sites which will help to develop and share good healthcare inequalities improvement practice across integrated care systems. Following a submission of interest in December 2022, Surrey Heartlands ICS has been identified as an accelerator site.

The inequalities may be at national programme level, regional level, local programme level and small geography (for example, local authority, hospital catchment or GP) level. Inequalities in cancer screening uptake also varies by demographic attributes, awareness of symptoms and attitudes/ beliefs towards cancer. Although local level data is not available, there are good sources of published evidence which highlights the key inequalities by such attributes (as described below).

Inequality by socioeconomic factors

Evidence shows large inequalities in the uptake of cancer screening services in socio-economically deprived areas. This has been shown in relation to the uptake of bowel, breast and cervical screening programmes in women in more deprived areas when compared to least deprived areas. Uptake of bowel cancer screening in England is lower in the ethnically diverse areas (38% compared to 52% to 58% in other areas) (Von Wagner et al, 2011; Cancer research UK, 2016; Tanton et al, 2015; Douglas et al, 2016).

Inequality by gender

Women in more deprived areas have shown to have a lower uptake of bowel, breast and cervical cancer screening programmes. Men have a lower uptake of bowel cancer screening (51% compared to 56% for women) but are more likely to be diagnosed and die from bowel cancer (male: female ratio 12:10) (Von Wagner et al, 2011; Moser et al, 2009; Marlow et al, 2015).

Inequality by ethnicity

Women from ethnic minority groups are less likely to attend cervical cancer screening compared to white British women. This disparity varies amongst different ethnic groups, for example the likelihood of non-attendance for Indian and Bangladeshi women have been shown to be lower compared to white British women. There is some evidence that women from ethnic minority groups are less likely to attend breast cancer screening compared to white British women (Renshaw et al, 2010; Jack et al, 2014).

Inequality by age

Cervical cancer screening uptake is markedly higher among 50 to 64 year olds than among 25 to 49 year olds. Age-specific incidence rates rise sharply from around age 15 to 19 and peak in the 30 to 34 age group, then drop until age 50 to 54, fluctuating in the older age groups and falling again in the oldest age groups. The highest rates are in in the 30 to 34 age group (Cancer Research UK, 2023).

Inequality by disability

Women with disabilities are less likely to participate in breast cancer screening and bowel cancer screening. This is particularly the case for those with disabilities relating to self-care or vision, or for those with three or more disabilities. Women with learning disabilities are also less likely to participate in cervical cancer screening compared to those without learning disabilities (Floud et al, 2017; Osborn et al, 2012).

The local Learning Disabilities Mortality Review (LeDeR) programme annual report from 2020/21 in Surrey, found that there has been a very low uptake of cancer screening across the breast, bowel and cervical cancer screening programmes. Screening information was unavailable for approximately 50% of the deaths reviewed. The reviewers found it difficult to obtain information from both health records and interviews. This may demonstrate a lack of confidence in this area or a lack of appreciation of the importance of screening in ensuring that people with learning disabilities have their health needs met in a proactive manner.

Further work is required to understand screening uptake better. The current work on the Surrey Care Records may aid reviewers to obtain more detailed information. Screening will be a key focus of LeDeR going forward.

Health literacy and cancer awareness

Differences in health literacy, awareness of symptoms and attitudes about cancer have also reported to be the known contributing factors in low cancer screening uptake. These have also been linked to healthier behaviours and the stage of diagnosis.

Although the inequalities in screening have been well documented, we do not know the full extent of inequalities within all our screening programmes because:

- We do not currently collect the relevant data, particularly in relation to local barriers on screening uptake amongst vulnerable populations and seldom herd groups.

- Data may be collected on IT systems but is not easily accessible to us.

- There is a lack of evidence on the reasons for the inequality and how we can effectively tackle the issues.

In addition, even when people who experience health inequalities attend for screening, the system and process may disadvantage them from maximising the benefits of screening. Therefore, the actions we take need to provide us with the information necessary to reduce the impact of inequalities in screening. This includes enabling collection of data by key demographic and socio-economic data and research to better understand local barriers in screening uptake (PHE Screening inequalities strategy – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)).

Bowel cancer screening

Bowel cancer screening: identifying and reducing inequalities has information for health professionals to support eligible people with learning disabilities to access and understand bowel cancer screening.

Breast screening

Breast screening: identifying and reducing inequalities has guidance and shared practice for breast cancer screening providers, commissioners and other stakeholders on addressing inequalities throughout the screening pathway.

Cervical screening

Cervical screening: supporting women with learning disabilities has information for health professionals to support eligible people with learning disabilities to access and understand cervical cancer screening.

Cervical screening: support for people who find it hard to attend has guidance for people who find it hard to attend cervical cancer screening due to having a mental health condition or having experienced trauma or abuse.

Cervical screening: ideas for improving access and uptake has guidance to help primary care, commissioners and local authorities plan and evaluate initiatives around cervical cancer screening coverage in their area.

What is this telling us? – cancer screening (bowel, breast, cervical)

Bowel cancer screening uptake rates are currently well above ‘achievable’ targets. There was a slump during the COVID-19 pandemic, but these have since recovered. Coverage rates have steadily increased to well above pre-pandemic levels.

Breast cancer screening coverage rates reduced significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic but have since recovered, due in part to the actions and efforts of the cancer screening services. Uptake rates usually hover around the ‘acceptable’ target, but these reduced substantially during COVID-19. Ongoing work is needed to recover rates to the ‘achievable’ targets for both coverage and uptake.

Cervical screening coverage rates are well below the target of 80.0%.

The screening process can be difficult for some people with physical disabilities, mental health conditions, learning disabilities or autistic people. Issues can be related to use of the screening equipment, the information/instructions provided or in attending screening appointments. Organisations should consider potential challenges for specific population groups in delivery of the screening service, whilst also taking into account learning from the LeDeR report 2020/21.

Non-cancer screening

Contents

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening programme

- Diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

- Antenatal and newborn (ANNB) screening programme

- Who’s at risk and why?

- Fetal anomaly screening programme (FASP)

- Infectious diseases in pregnancy screening (IDPS) programme

- Sickle cell and thalassaemia (SCT) screening programme

- Newborn and infant physical examination (NIPE) screening programme

- Newborn blood spot (NBS) screening programme

- Newborn hearing screening programme (NHSP)

- Who’s at risk and why?

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) Programme

Who’s at risk and why?

The aorta is the main blood vessel that supplies blood to the body. It runs from the heart down through the chest and abdomen. In some individuals, as they get older, the wall of the aorta in the abdomen can become weak. It can then start to expand and form an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Men aged 65 years and over are most at risk of AAA.

Large aneurysms are rare but can be fatal. As the wall of the aorta stretches it becomes weaker and can burst. Around 85 out of 100 people die when an aneurysm bursts. An aorta which is slightly larger than normal is not dangerous, however it is still important to know about it so that it can be checked to see if an aneurysm is getting bigger.

Individuals who have an aneurysm will not usually notice any symptoms. This means people cannot tell if they have one, will not feel any pain and will probably not notice anything different.

Screening is offered to find aneurysms early and to monitor or treat them, this greatly reduces the chances of the aneurysm causing serious problems. Around 1 in 92 men who are screened have an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Men are 6 times more likely to have an abdominal aortic aneurysm than women, which is why women are not offered screening.

The chance of having an aneurysm increases with age and can also increase if the individual:

- is or has ever been a smoker

- has high blood pressure

- their brother, sister or parent has, or has had, an AAA

Those ineligible and not routinely invited for AAA screening includes:

- men under the age of 64 years

- men already scanned through national AAA screening programme and the aorta was within normal limits

- men previously diagnosed with an AAA

- men previously undergone surgery for AAA repair

- men aged 65 years or over and on local surveillance for an AAA

- men whose GP advises that they should not be screened due to other health conditions

- women

Further information can be found for trans and non-binary people at: NHS population screening: information for trans and non-binary people – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening programme

The NHS abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening programme is available for all men aged 65 years and over, and registered with a GP in England. The programme aims to reduce AAA related mortality among men aged 65 to 74.

AAA screening is offered to men during the screening year (1 April to 31 March) that they turn 65 years old. They will receive an invitation in the post for screening. Men over 65 years who have not received an invitation can contact the local AAA screening service to make an appointment. Any women, or men under 65 years who think they are at higher risk (for example, due to family history of the condition) can talk to their GP about the possibility of having a scan outside the screening programme.

Further information can be found at: Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening: programme overview – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening data

The NHS key performance indicator for abdominal aortic aneurysm screening coverage is defined as: “The proportion of men eligible for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm screening who are conclusively tested.”

The national screening programme has an “acceptable” performance threshold for abdominal aortic aneurysm screening of 75.0% of the eligible population and an “achievable” level of 85.0%.In 2021/22 the performance level achieved by Surrey (49.4%) was significantly lower than the “acceptable” target. The performance level achieved was also lower than the “acceptable” target in the South East (63.5%) and England (74.9%).

The latest full year data available is for 2021/22. The trend based on data since 2017/18 in Surrey and England has shown overall to be decreasing and getting worse. Coverage for screening peaked in 2018/19 for both Surrey (83.2%), South East (82.4%) and England (81.3%).

In both 2019/20 and 2020/21 there was a worsening trend in all areas. The lowest figures were in 2020/21 for Surrey (35.2%), South East (63.5%) and England (55.0%).

In 2021/22, the proportion of eligible people screened in Surrey improved (49.4%) but was still worse than in the South East (74.9%) and for England (70.3%). This however is a higher coverage than in 2020/21 for Surrey, South East and England.

Note: The data dashboards linked to this JSNA chapter can also be searched to find GP practice level data.

Services in relation to need – abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

| Screening programme | Service in Surrey |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening programme | Established April 2012. The NHS AAA screening programme is available for all men aged 65 years and over in England. Two programmes for the Surrey population – South London programme covering East Surrey (commissioned by NHS England London Region) – West Surrey and North Hampshire programme at Ashford and St Peters Hospitals. |

Local Insights – abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

Feedback from members of the Surrey Coalition of Disabled People

For the AAA screening one member couldn’t find out if the venue he was being sent to for the test had a hearing loop, so he made an extra trip ahead of time and discovered it didn’t.

Our member said: “In the event of a need for a further test, will the letter tell me to phone if I need to change the […] appointment that will be offered? I find the prospect off-putting, and it certainly doesn’t encourage me to do the screening test.”

What are the unmet needs/service gaps? – abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

- There is limited resource within screening to address health inequalities as local providers cannot identify people who may require reasonable adjustments.

- National data cannot be broken down to identify uptake for people with learning difficulties and/or autism.

- Further work is required to improve communication between GPs and screening providers.

- Letters in different languages and in easy read format are available, however the service cannot identify the people who require these when invitation letters are sent.

What are the key inequalities? – abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

The following is available at the West Surrey and North Hampshire screening programme to try to reduce inequalities:

- easy read leaflets

- leaflets in other languages

- interpreter services including British Sign Language

- Red Cross emergency communication book

- clinics in prisons and secure units (HMP Coldingley and St Magnus – the service contact the female prisons to offer the service to transgender patients).

- staff training with the primary care liaison nurses (learning disability awareness)

Currently, the West Surrey and North Hampshire screening programme is not made aware of any patients who may require a reasonable adjustment for their appointment. Invitation letters are sent to all the cohort patients and the staff are not usually aware if the patient requires a reasonable adjustment until they arrive in clinic, unless the patient/relative or carer contacts the clinic to let them know.

In the future, AAA providers may be able to access the Reasonable Adjustment Flag, which is being developed by NHS Digital and NHS England to enable services to record, share and view details of reasonable adjustments across the NHS.

The following is available at the South London screening programme (which covers East Surrey) to try to reduce inequalities:

- They are Accessible Information Standard (AIS) compliant and AIS standard is updated annually. Reasonable adjustments are provided when requested.

- Easy read leaflets are offered and longer appointments can be arranged if required.

- Language is recorded at point of contact with the service user, however this is also provided by the GP. Consent and results can be provided electronically in certain different languages, as required.

- Telephone interpreter services plus face-to-face interpreters for British Sign Language and deaf/blind service users.

- Clinics in prisons and secure forensic units. Lists of men aged over 64 years in prisons and forensic units are validated by the administration team on a quarterly basis.

- Text message reminders are sent 10 days and 2 days prior to the appointment.

- Alternative venues listed on the reverse of the invite. Map of the venue with accessibility information included.

- The inequalities tool is run quarterly from their database to identify service users living in the most deprived areas of South London and East Surrey.

The South London screening programme said the GP information is not hugely accurate hence they tend to rely on men or their carers, next of kin etc. contacting them with their communication needs.

They are hoping to do some work on meeting with the disability liaison nurses this year (2023/24) with the aim to email the LD nurses with the easy read leaflet, a link to a video on the screening process, and a poster on the importance of AAA screening. They will also share the consent process and decision aid, so that service users can make an informed decision on accepting or declining their screening invitation.

The service is also planning a project on pushing uptake amongst the most deprived lower super output areas (deciles 1-3). As a service, they are given the confidential identification of service users who live in areas classed as decile 1-3. Once they have caught up on the backlog from 2022/23, they hope to do more work on improving attendance amongst this cohort. In Surrey less than five percent of the population live in an area classed as decile 1-3, and the uptake is already high.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening: reducing inequalities has guidance to support AAA screening providers, commissioners and other stakeholder by sharing learning and good practice in reducing barriers to attendance.

What is this telling us? – abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

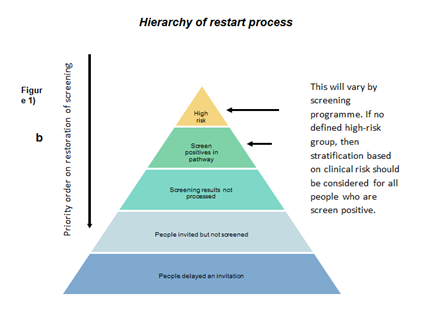

During March 2020, all 38 local NHS AAA screening services stopped inviting (rescheduled) men for screening due to the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Information, guidance and advice was gathered from the local NHS foundation trust (Ashford and St Peters), Public Health England (PHE) (Note that Public Health England was disbanded in 2021. Its functions were taken over by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) in the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), and NHS England (NHSE)), the British Government and other healthcare professionals to plan the safe restart to the screening programme. Programmes were able to restart inviting patients for screening in August 2020, following the hierarchy order shown below, as per the PHE restoration guidance:

- High risk men – men with large AAA (>5.5cm)

- High risk men – men with a medium AAA (5-5.4cm)

- Men with medium AAA (4.5-4.9cm)

- Men with small AAA (3-4.4cm)

- Screening results not read-assessed

- Men invited but not screened

- Men delayed an invitation in the 2019/20 and 2020/21 cohorts

- Self referrals

The East Surrey population is covered by the South London AAA screening programme which is commissioned by NHS England London. For the East Surrey area all eligible people from the 2022/23 cohort have been offered a screening appointment. Mass screening events have been held in the Dorking area to clear backlogs for that population, with other mass screening events held in Horley and Leatherhead in Spring 2023.

The rest of the Surrey population is covered by the West Surrey and North Hampshire screening programme. This programme is still likely to experience impact following the COVID-19 pandemic into 2023/2024 with the cohort taking longer than pre-pandemic/expected to complete screening.

The West Surrey and North Hampshire screening programme has faced several issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the following:

- pause in clinics

- staff sickness

- loss of clinic locations

- staff training/recruitment issues

- national lockdowns

- appointment times doubled (to allow staff to change personal protective equipment and for cleaning processes to take place)

- staff and patients wearing personal protective equipment

- one-way systems introduced in surgeries for social distancing

- decrease in uptake due to patient concerns regarding COVID-19.

In order to try and bring the expected completion date forward for the 2022/23 cohort, the following is being carried out:

- screeners are carrying out bank clinics

- fortnightly Saturday clinics are being held

- assistance has been received from other AAA Screening programmes.

Diabetic Eye Screening Programme (DESP)

Who’s at risk and why?

In 2021/22 there were around 3.6 million people (7.3% of the population) aged 17 and older known to have diabetes mellitus in England and 60,328 (5.8%) in Surrey (further diabetes prevalence data is available on Public health profiles – OHID (phe.org.uk)). Diabetic retinopathy is a complication of diabetes caused by fluctuating blood sugar levels damaging the blood vessels in the back of the eye (retina). Diabetic retinopathy can be asymptomatic in the early stages and over time can cause vision loss if left undiagnosed and untreated. Diabetic retinopathy was formerly the leading cause of blindness in the working age population in the UK but following the successful implementation of PHE (now NHS) diabetic eye screening programmes, a study in 2009 found that it had been relegated to number two, behind hereditary retinal disorders. Diabetic eye screening enables this disease to be promptly identified and treated where possible, thus reducing the risk of sight problems or subsequent vision loss.

Research by the Royal National Institute for Blind People suggests that 50 percent of cases of blindness and serious sight loss could be prevented (Access Economics, 2009; Sight loss: a public health priority, 2014 cited in Public health profiles – OHID (phe.org.uk)) if detected and treated in time. Whilst this is mainly due to uncorrected refractive error and untreated cataract, the research implies that the take up of sight tests is lower than would be expected. This is particularly the case within areas of social deprivation. Low take up of sight tests can lead to later detection of preventable conditions and increased sight loss due to late intervention. In 2021/22 in Surrey, there were 28 (2.7 per 100,000) new certifications of visual impairment due to diabetic eye disease in people aged 12 and over (the latest data on certification of visual impairment is available on Public health profiles – OHID (phe.org.uk).

Reducing the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy can be performed by:

- controlling blood sugar/pressure and cholesterol levels

- taking diabetes medication as prescribed

- attending all diabetic eye screening appointments

- obtaining ophthalmological advice quickly if vision suddenly changes

- maintaining a healthy weight, by eating a healthy, balanced diet and exercising regularly

- stopping smoking.

The risk of developing retinopathy can be reduced by good management and control of diabetes (glycaemia control) and blood pressure.

The NHS diabetic eye screening programme aims to reduce the risk of sight loss among people with diabetes by the early detection and treatment, if needed, of sight-threatening retinopathy.

Diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

Diabetic eye screening is offered to anyone with diabetes who is 12 years old or over, who has been formally diagnosed as having diabetes (excluding gestational). They are most commonly invited at least once a year, however those requiring more regular monitoring will be offered screening more frequently. Service users for whom the DESP has evidence of them being regularly seen in their hospital eye service for diabetic eye checks, are not invited to the DESP until they are discharged by the hospital.

Further information can be found at: Diabetic eye screening: programme overview – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

In Surrey there are three pathways that can be taken:

- Routine Digital Screening (RDS) where service users are invited for eye screening once a year.

- Digital Surveillance (DS) which may involve more frequent monitoring.

- Slit Lamp Biomicroscopy (SLB) which may involve more frequent monitoring.

Diabetic eye screening programme (DESP) data

NHS screening key performance indicators define routine digital screening uptake as: “The proportion of those offered RDS who attend a routine digital screening event where images are captured.”

Data is recorded for Surrey as a whole and is compared to the England average. The latest full year data available is for 2021/22. Between 2017/18 and 2019/20 Surrey yearly average uptake rates have generally been good ranging between 79.4% and 82.3% performing well above the “acceptable” target level of 75.0% but not meeting the “achievable” target level of 85.0%. Similarly to that of Surrey, the yearly average uptake rates were fairly constant between 2017/18 and 2019/20 in England (ranging between 81.5% and 82.6%) and across the South East region (ranging between 81.6% and 83.8%). However the average rates dropped during 2020/21 in England (67.9%), the South East (79.2%) and Surrey (66.2%). In 2020/21 Surrey failed to meet the “acceptable” target level, similar to the rest of England. The drop in rate for Surrey and across England in 2020/21 could be attributed to restrictions put in place and difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting operational backlogs.

Rates significantly improved in 2021/22, compared to 2020/21. The Surrey yearly average uptake rate rose to 81.6% in 2021/22, well above the “acceptable” target level of 75.0% but failed to meet the “achievable” target level of 85.0%. In 2021/22 the rate in Surrey was higher than England (78.4%) but lower than the South East (83.0%).

Note: The data dashboards linked to this JSNA chapter can also be searched to find GP practice level data.

NHS screening key performance indicators define timeliness of results letters as: “The proportion of eligible people with diabetes attending for diabetic eye screening, digital surveillance or SLB surveillance to whom results were issued 3 weeks or less after the screening event.”

Data is recorded for Surrey as a whole and is compared to the England average. Over recent years Surrey as a whole performed well above the “acceptable” target level of 70.0% and the “achievable” target level of 95.0%.

Full year rates presented here are between 2017/18 and 2020/21. Surrey yearly average rates have generally been very high over the period. In 2017/18 the rate was 87.7%, higher than the “acceptable” target level but not meeting the “achievable” target level. However, since then rates have greatly improved, achieving 99.7% in 2018/19, 99.8% in 2019/20, and 99.6% in 2020/21. The England yearly average rates have steadily improved from 94.3% in 2017/18 and rising to 98.8% by 2020/21.

Services in relation to need – diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

| Screening programme | Service in Surrey |

| Surrey diabetic eye screening programme (DESP) | Nippon Electric Company (previously known as ‘Northgate’), independent provider across Surrey. In 2022, the Surrey DESP managed to appoint all service users and catch up on all the backlogs resulting from COVID-19, restoring the service capacity back to pre-COVID-19 levels – one of the few DESPs in the country to achieve this. |

The Surrey DESP currently has 62,164 (February 2023) service users and using the three different pathways it is commissioned to provide, it screened:

- 40,465 in RDS – annual screening for low risk of vision loss

- 1,406 in DS – more regular monitoring for higher risk, but not sufficient for ophthalmology referral

- 2,693 in SLB – where a slit lamp is required, as a digital camera is unable to capture grade-able images.

The rates for people with appointments (2020-2021) who did not attend on the day was the highest it has ever been at 44% for RDS (due to the service appointing all service users, including serial non-responders), 17% for those for DS and 10% of the SLB cohort. Only 0.1% of service users were referred on to their ophthalmology acute services as urgent and 1.1% as routine.

Local insights- diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

There are approximately 115 GP practices across Surrey engaged with the DESP service. There are 16 screening sites across Surrey including rotational sites to cover less densely populated areas. Patients who require further investigation can be referred to the ophthalmology department at five hospital trusts.

To maintain the accuracy of data and ensure that no service users are missed, the services use ‘’GP2DRS’’, which all Surrey DESP GP surgeries are signed up for. This is an automated monthly extraction of all people on their diabetes register. All demographic updates are then imported into the services database which allows the capture of all newly diagnosed, and new to the GP surgery, people with diabetes. The central Failsafe and administration teams undertake all required audits at the nationally mandated intervals (monthly, 6 monthly or annually) to ensure that all database cohorts are correct.

All screeners and screener/graders are fully trained both in regular local competencies as well as achieving the national Health Screening Diploma (which takes 18-24 months to complete). All graders must undertake the national test and training image set on a monthly basis and meet the required grade, which measures their grading accuracy against others in their local team and also gives a comparison against other teams nationally. Intergrader agreement is also measured in the service software and reviewed on a quarterly basis with each grader and a team leader or the clinical lead (Consultant Ophthalmologist).

The service user satisfaction survey is currently undergoing revision following feedback from staff and service users. Survey links are printed on information leaflets given at each screening appointment and also sent by SMS to each attendee with a mobile phone number, if they have consented to receive SMS reminders and relevant messages. Surveys are collated and data reviewed monthly, with suggestions and issues being acted upon for learning and service improvement.

The service found through audits that the cohort with the lowest attendance rates tended to be those of the working age population. The service offers Saturday clinics to make it easier for more people to attend. This also benefits those service users who rely on people working during the week to transport them to their appointments.

What are the unmet needs/service gaps? – diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

The service is working hard on the serial non-engagers, but this is extremely labour intensive for minimal return.

It is not possible to offer individual screening appointments for care homes and those service users who are housebound. For care homes with more residents, it would require a lot of preparation in advance. Two screeners are needed to move equipment and provide the actual screening, which would mean cancelling of two full clinics in the usual venues. It is also hard to gauge if screening would be physically possible for the small numbers requiring it.

The service is working on strengthening links with psychiatric hospitals, mental health services and residential places, but again there are very small numbers. It is difficult when service users can’t go to clinics in the community and where it may not be safe for staff or the equipment to go into residential institutions.

Local domiciliary optometrists and opticians do provide home visits and standard NHS vision assessments for those housebound, but this is external to the Surrey DESP service.

Service users unable to be screened using equipment in the DESP clinics are referred on to their local hospital eye service, where they have more suitable equipment to meet additional physical needs.

What are the key inequalities? – diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

The DESP service has a number of service options to help reduce key inequalities. Female screeners are available for those who request them. A variety of languages are spoken by screeners, or if they are caught unaware, screeners can phone Big Word Interpreter Phone Services or use Google Translate as a last resort. The service has links with local mosques and local ethnic minority groups which are visited to promote engagement, for example, the Nepalese community in Camberley/Ash area. This is important as people from Black African, African Caribbean and South Asian backgrounds are at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes from a younger age (Diabetes UK, 2023b). If notified in advance, British Sign Language interpreters from Sight for Surrey can be provided if needed and all clinics have the required questions and instructions printed out for people at the point of screening. National leaflets are available online in easy-read format, as well as other languages.

Surrey DESP service visits all five prisons across the county every 3 to 6 months, working closely with their medical teams to ensure good uptake. The service also works closely with Surrey and Borders Partnership Primary Care Learning Disability Liaison Team to ensure screeners have regular up to-date training and to ensure links with GP surgeries around shared learning disability services users are robust. Learning disability or mental health service users requiring reasonable adjustment and additional support are catered for where possible.

Pregnant women / birthing people are offered more regular appointments to monitor changes (due to increase of growth hormones). The team engages with GP surgeries that have the lowest uptake, but generally find that non-engaging service users tend not to engage with their GP surgeries either.

What is this telling us? – diabetic eye screening programme (DESP)

DESP uptake rates generally perform above the “acceptable” target level but did drop off during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most recent data shows that uptake rates have bounced back but not yet meeting the “achievable” target (85.0%).

In terms of timeliness of results, rates are well above the “achievable” target rate (95.0%).

The service has caught up with all the COVID-19 backlog, restoring service capacity back to pre-pandemic levels. The service is working efficiently with suitable systems in place and links to GP practices to ensure all people eligible are invited for a screen. The service works hard to reduce inequalities and offers options to help those who might otherwise be reluctant to attend an appointment, for example providing female screeners, translation services, weekend appointments and, screens within local prisons.

Local challenges include following up non-attenders, providing appointments in care homes or for people who are housebound, or in psychiatric or mental health residential institutions.

Antenatal and newborn (ANNB) screening

Who’s at risk and why?

Risk factors for the problems identified through antenatal and newborn screening include:

- family history

- genetic factors

- ethnicity

- age of mother

- infectious disease during pregnancy.

The screening tests offered during pregnancy (antenatal) in England are either ultrasound scans or blood tests, or a combination of both. Ultrasound scans may detect conditions such as spina bifida. Blood tests can show whether there is a higher chance of inherited conditions such as sickle cell anaemia and thalassaemia, and whether pregnant women / birthing people have infections like HIV, hepatitis B or syphilis.

Blood tests combined with scans can help find out how likely it is that the baby has Down’s syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome or Patau’s syndrome.

Newborn screening tests are offered soon after a baby is born. This is so that a baby can be given appropriate treatment as quickly as possible if needed.

Whether or not to have each test is a personal choice and one which only the pregnant woman / birthing person can make. Everyone can discuss each test they are offered with health professionals and decide, based on their own circumstances, whether or not it is right for them. They can also change their mind at any stage.

Some of the screening tests described below, such as blood tests for infectious diseases, eye screening if they have diabetes and the newborn checks, are recommended by the NHS. This is because results from these tests can help make sure that the pregnant woman / birthing person and their baby gets urgent treatment for serious conditions.