Emotional and Mental Wellbeing in Surrey Adults

Emotional and Mental Wellbeing in Surrey Adults

Publication date

This chapter was published in March 2023 and is due to be reviewed by March 2025.

Contents

- Common Mental Health Problems

- Incidence Adult Mental Health Problems

- Index of Multiple Deprivation – Mood and Anxiety Indicators

- Self-reported Wellbeing

- QOF: Depression

- Long Term Mental Illness

- QOF: Severe Mental Illness (SMI)

- Suicide and Injury Undetermined

- Eating Disorders

Socio-economic, Cultural and Environmental Conditions: The Current Context

Living and Working Conditions

Community Safety and Feeling Safe

Workplace and Employment

Health Environment

Social Isolation and Loneliness

- Populations at Risk

- Young Adults

- Adults

- Perinatal

- Older People

- Carers

- Ethnicity

- Gypsy, Roma, Traveller (GRT) Communities

- People with Learning Disability

- Neurodivergence

- Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Migrants

- Adverse Childhood Experiences/Life Events

- Experience of Bereavement

- Relationship Breakdown

- Multiple Adverse Life Events

- Sexuality/LGBTQ+

- Armed Forces Community Veterans

- Physical Health and Health Behaviours

- Physical Health

- Access to Healthcare

- Health Behaviours

- Substance Use

- Hospital Admissions due to Alcohol

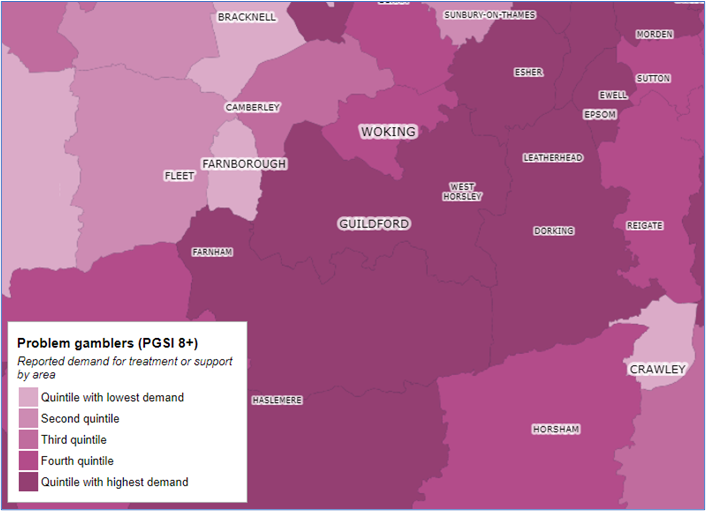

- Gambling

Universal Services

- Adult Social Care Mental Health Team

- Digital

- Local Insights

- Social Prescribing

- Green Social Prescribing

Primary Care

Secondary Care

- Acute Mental Health Hospital Admissions

- Emergency Mental Health Hospital Admissions

- Detentions under the Mental Health Act

- Section 136 Detentions

- Emergency Admissions for Self-Harm

- Avoiding admission to mental health hospitals, and how discharges could be safely made more quickly.

- Concurrent Contact Mental Health and Substance Use Services

- Factors Supporting Recovery: Addressing Stigma

- Factors Supporting Recovery: Employment

- Factors Supporting Recovery: Care Planned Approach

- Factors Supporting Recovery: Wellbeing

- Recommendations for Policy Makers and Commissioners

- Area 1: Population prevention. Tailor, develop and promote place-based population wellbeing approaches including the determinants of wellbeing.

- Area 2: Communities. Utilise research and coproduction of wellbeing and mental health services with people with lived experience, residents (via community development) and VCSE sector provision.

- Area 3: Address current and predicted unmet need with further equality impact assessments in key areas.

- Area 4: Develop pathways that support holistic approaches including escalation and de-escalation across the system.

- Area 5: Ensure seamless read across with Children and Young People’s needs assessment to inform whole family responsive pathways.

Appendices

- A – References

- B – Health and Wellbeing Board Matric

- C – Common Mental Health Conditions

- D – Prevention Interventions

Overview

This chapter explores the emotional and mental wellbeing of residents of Surrey. The chapter considers social and environmental influences on the mental health of residents in Surrey. This is followed by an overview of services in place in Surrey. The chapter also consider mental health for key population groups in Surrey, many of which form part of the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy Priority Populations.

This chapter is one of four current chapters considering Mental and Emotional Wellbeing in Surrey Residents across the life course.

| Starting Well (0-4) | Perinatal |

| Developing Well (5-16) | Emotional Wellbeing and Mental Health Children & Young People |

| Transitioning to Adulthood (17-24) | Both the Adult and the Children & Young People chapters |

| Living Well (25-64) | Emotional and Mental Wellbeing in Surrey Adults |

| Aging Well (65+) | Dementia |

Loneliness and Isolation chapter (To be produced in 2023)

This chapter is based on the latest available population data at October 2022. The chapter is informed by the Mental Health Tableau Dashboard which has been developed locally by the Public Health Intelligence and Insight Team in Surrey County Council. It will be replaced with an expanded Dashboard that is being developed. The Public Mental Health Dashboard developed by Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) for use by local authority Public Health teams and others has also been applied throughout this chapter.

1. Executive Summary

The chapter outlines the most up to date intelligence of expressed and expected need for mental and emotional wellbeing in Surrey. The key protective factors for good emotional and mental wellbeing are considered alongside data sources which can support further exploration of opportunities for intervention at place. The following key strategic drivers for mental and emotional wellbeing in Surrey, were considered in the writing of this chapter.

- Health and Wellbeing Strategy.

- The Fuller Stocktake recommendations for community led action.

- CORE20Plus5 for adult mental and emotional wellbeing are considered.

The chapter is informed by the Mental Health Tableau Dashboard which has been developed locally by the Public Health Intelligence and Insight Team in Surrey County Council (SCC). The tableau dashboard for mental and emotional wellbeing provides links to graphs and intelligence on demand for services and intelligence on vulnerable populations. The body of the chapter draws out the factors related to risk and protection of good emotional and mental wellbeing which can be applied to data sets on geographies as required for targeted intervention design. The Public Mental Health Dashboard developed by Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) for use by local authority Public Health teams and others has also been applied throughout this chapter.

The mental health system partnership collaboratively developed the chapter drawing on nationally available and local datasets to provide a repository of portals for accessing up to date information for surrey.

The chapter outlines specific tools and data sources to inform the development of place-based plans for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention and treatment, reviewing services for equity of access and outcomes. The chapter outlines key information for delivery of the health and wellbeing within Surrey.

Area 1: Population prevention: Tailor, develop and promote place-based population wellbeing approaches including the determinants of wellbeing.

Area 2: Communities. Utilise research and coproduction of wellbeing and mental health services with people with lived experience, residents (via community development) and VCSE sector provision.

Area 3: Address current and predicted unmet need with further equality impact assessments in key areas

Area 4: Develop pathways that support holistic approaches including escalation and de-escalation across the system.

Area 5: Ensure seamless read across with Children and Young People’s needs assessment to inform whole family responsive pathways.

2. Background

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community”. This document will consider mental health in adults. This will include factors which protect mental health and risk factors. The expressed need of residents in Surrey will be explored and recommendations made for addressing any gaps.

The Surrey Health and Wellbeing Board identified mental health as a priority to understand the need in Surrey to inform policy making and commissioning decisions.

3. JSNA Process

Aims

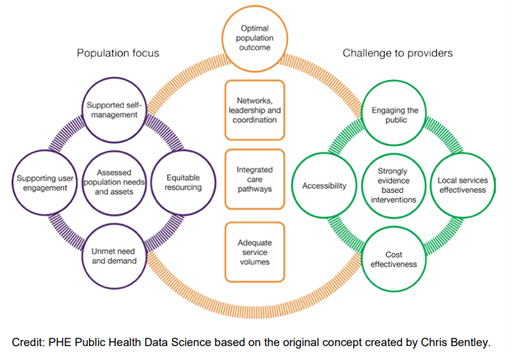

This Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) for Emotional and Mental Wellbeing in Surrey provides an overview of the mental and emotional wellbeing needs in Surrey to implement the OHID Toolkit A – Place Based Planning. This should enable population health system planning to meet the needs at scale.

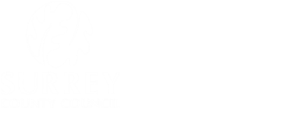

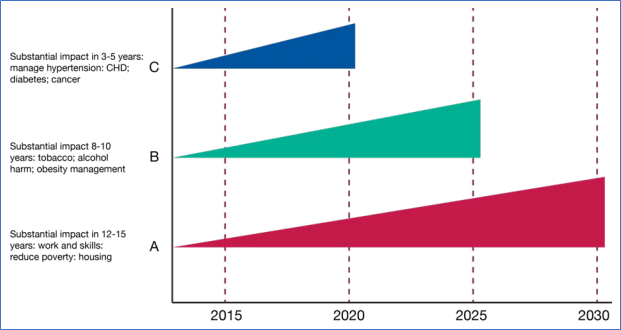

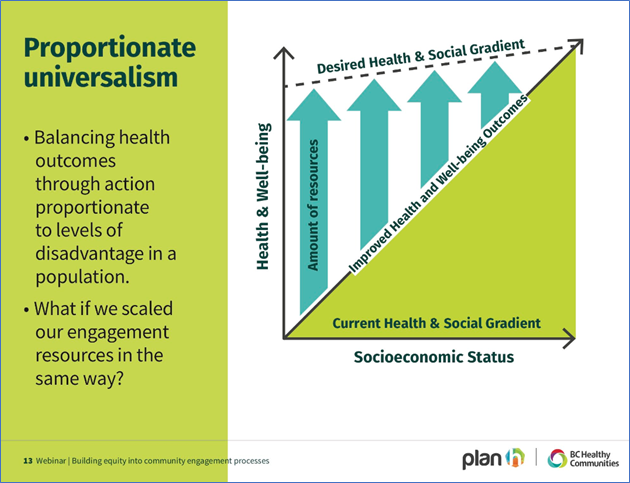

Figure 1. OHID Population Health Triangle

This JSNA should be used alongside the OHID Toolkit B – Civic Support to Communities and Toolkit C – Service to community, to ensure needs based, segmentation and coproduced planning at place. This JSNA should also be used to inform next steps taking into consideration the principle of ‘proportionate universalism’, resourcing and delivering of universal services at a scale and intensity proportionate to the degree of need.

Governance

The JSNA governance is defined and organised at four levels: Health and Wellbeing Board (HWB), JSNA Oversight Group (OG), JSNA Working Group and JSNA chapter delivery groups. The HWB has a statutory requirement to produce a JSNA and delegates the responsibility and management for the JSNA to the JSNA OOG.

The JSNA OG chaired by the Director Public Health provides senior management and executive leadership to the JSNA implementation and ensures that the JSNA remains aligned to the strategic joint priorities for the Surrey HWB and supports partnership working at different levels within Surrey.

Below the JSNA OOG and reporting to it is the JSNA Working Group. This consists of the lead officers of each of the JSNA chapters in production and is chaired by the Public Health Analyst Team Lead. The Working Group meets every three weeks to monitor chapter progress and share best practice. Daily the Chapter Delivery Group leads on chapter production, agreeing the scope, timelines, contributing authors and reported on progress to the working group.

Strategic Drivers and Evidence Base

Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy

Next steps for integration primary care: Fuller Stocktake report

Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s

Core20PLUS5 (adults) – an approach to reducing healthcare inequalities

As outlined in both the JSNA Chapter ‘Surrey Context: People and Places’ and the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy (HWBS), 21 Surrey wards have been identified as containing the most deprived Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) and are being prioritised in strategies and action plans. The HWBS also has people with Severe Mental Illness (SMI) as a priority population group.

The evidence base for interventions are considered across the life course:

| Living Well | New Economics Foundation (NEF) commissioned by central government’s Foresight Report which includes interventions to support own wellbeing (Five Ways to Wellbeing: the Evidence) and direction on how this could be used at scale for population level impact (The results of a scoping exercise to see how the Five Ways are being used) |

| Working Well | NICE Guidance for Promoting Wellbeing at Work 2022 (PH22) outlines strategic drivers, offers for the workforce and training to enhance wellbeing (Mental health and work, 2007, FPH) |

| Ageing Well | NICE guidance on mental wellbeing and older people (PH16) Older people: independence and mental wellbeing Mental wellbeing of older people in care homes Quick guide to promoting positive mental wellbeing for older people |

Interpreting data

The contents of this JSNA have been informed by OHID JSNA toolkit Mental Health and outcomes for Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy, Priority 2: Supporting people’s mental health and emotional well-being by preventing mental ill health and promoting emotional well-being (Appendix1). Where possible data is presented at Surrey County level and District & Boroughs level and compared to national, regional and where available Combined Intelligence for Population Health Action (CIPHA) will be used, for comparative data with the closest neighbour.

4. Mental and Emotional Wellbeing in Surrey

Common Mental Health Problems

Common mental health problems cover a broad range of individual mental health conditions. NICE lists depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in their definition of common mental health disorders. They are labelled as common as they affect more people than all other mental conditions combined. This section provides an overview of the prevalence of common mental health problems throughout Surrey, the impacts they have and the influence of wider determinants on their prevalence across Surrey. Other JSNA chapters such as the Substance Use chapter explore these conditions in more detail.

Up to date information is available on the Mental Health Dashboard: JSNA Mental Health Published Tableau Dashboard

Incidence Adult Mental Health Problems

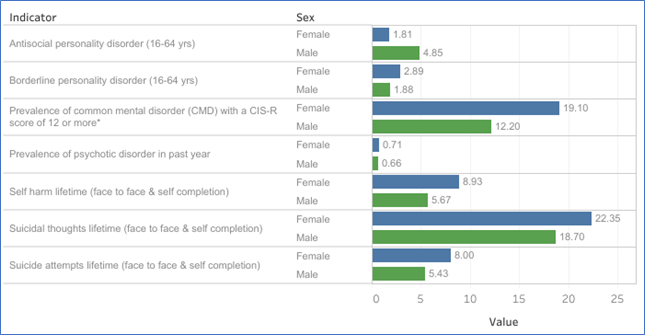

The national Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) is the only data source to assess/ screen for the prevalence of both treated and untreated mental disorders in England. This includes both people with diagnosed disorders and people who have not received a formal diagnosis. For this reason, the prevalence reported in the APMS is higher than those based on service data below.

The APMS demonstrates there is a considerably higher prevalence of mental health problems among the general population than the number of people receiving treatment. Often the stigma that surrounds mental health can make it harder for people to seek help from services, hence the importance of widely available self-help information and anti-stigma interventions.

The APMS Survey Common Mental Disorders (CMD) are listed as depression, Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Panic Disorder, Phobias, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and CMD-Not Otherwise Specified (CMD-NOS).

The APMS survey uses the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R) to assess for the prevalence of CMDs. The CIS-R is a standardised, structured assessment interview used to measure the presence of nonpsychotic symptoms.

Key national findings on Common Mental Disorders (CMDs), from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS):

- 18.9% of adults aged 16-64 in 2014 reported having a CMD in the past week. This rate increased from 17.6% in 2007.

- More women than men reported having a CMD in the previous week (23.1% vs 14.7%) (2014).

- Of the 9 England regions, the South East had the lowest age-standardised and observed rates of people with any CMD in 2014 (13.6% & 13.6% respectively).

- Gaps in self-diagnosis and professional diagnosis have been observed. In 2014, 43.4% of respondents stated they had at some time, self-diagnosed a CMD, whereas only 27.4% reported ever being professionally diagnosed for a CMD.

One measure of the severity of neurotic symptoms is the CIS-R score. A score of 12 or greater indicates symptoms of anxiety and depression of a level likely to benefit from acknowledgement and possible intervention.

The number of people aged between 16-64 report scores of 12 or greater rose from 14.1% in 1993 to 17.5% in 2014.

The proportion of people aged 16-64 in 2014 with CIS-R scores of 12 or greater was larger in women than men, 21.4% vs 13.6%.

National key CMD findings from the APMS pertaining to the wider determinants of health:

Prevalence of any CMD in last week by household type varied greatly.

- Prevalence was highest among 16-59 year olds living in a single adult house with no children (29.4%)

- Prevalence was lowest in those living in households of 2 adults, one or both 60+, with no children (10.4%)

Prevalence of any CMD in last week by employment status varied greatly.

- Those in full-time employment with 2.1 times less likely to experience a CMD in the previous week, compared to the economically inactive.

- Prevalence of any CMD in the last week by benefit status also varied

- Respondents receiving Employment and Supporting Allowance were 3.8 times more likely to report experiencing a CMD in the last week than those that did not

- Those receiving out-of-work benefits were 2.9 times more likely to report a CMD in the last week and those receiving Housing benefit were 2.5 times more likely to report a CMD in the last week.

[It is recognised that this data is historic, when 2021 data is available from OHID it will be added here. There is currently no indication of publication date.]

There was a predicted 1.3% increase in mental disorder (diagnosed and undiagnosed) in 16-64 years between 2017/ 2020.

Number of people in Surrey aged 16-64 predicted to have a mental disorder

| Indicator | 2014 | 2017 | 2020 | % Change |

| Estimated number predicted to have these conditions | 180,346 | 182,747 | 1.3% | |

| Estimated population 16-64yrs | 733,113 | 742,872 | 1.3% | |

| Have borderline personality disorder | 2.4% | 17,595 | 17,829 | |

| Have a common mental disorder | 18.9% | 138,558 | 140,403 | |

| Have an antisocial personality disorder | 3.3% | 24,193 | 24,515 | |

| Have a psychotic disorder | 0.7% | 5,132 | 5,200 |

Table 1. Number of people 16-64 years in Surrey predicted to have mental disorder Source: OHID Fingertips

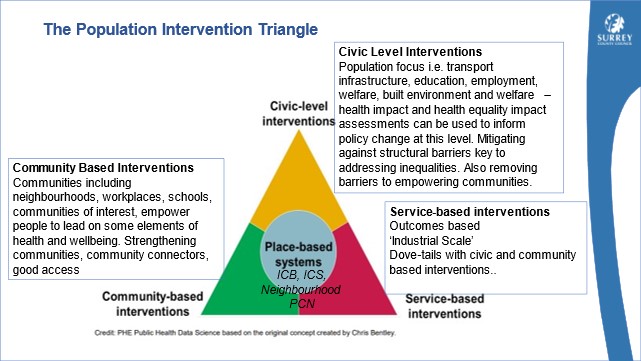

Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) – Mood and Anxiety Disorders Indicator

Common mental ill health is defined as suffering from mood (affective), neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders. The prevalence of these are based on prescribing, suicides and hospital admissions data.

The IMD Mood and Anxiety Disorders indicator is used widely to analyse patterns of common mental ill health by Lower Super Output Area (LSOA). These are areas of roughly 1,500 residents. A score of zero represents the average prevalence across all LSOAs in England. A score above zero indicates that a higher prevalence of mental health problems is evident in an area than expected, given the age and gender distribution. A higher score for the indicator represents a higher level of mood and anxiety deprivation.

In 2019, indicator values in England ranged from 3.095 to -3.045. In Surrey, values ranged from 1.203 to -1.915. Overall common mental health needs in Surrey are relatively lower than across England as a whole. The data visualisation shows the level of deprivation across LSOAs within Surrey, as measured by the IMD Mood and Anxiety Disorders indicator (2019). The five LSOAs with the highest levels of mental health needs are in Reigate and Banstead. In descending order, they are.

Reigate and Banstead 008A – Hooley, Mersham & Netherne

Reigate and Banstead 016E – Horley West & Sidlow

Reigate and Banstead 015E – South Park & Woodhatch

Reigate and Banstead 005A – Tattenham Corner & Preston

Reigate and Banstead 008B – Hooley, Mersham & Netherne

Figure 2. Mood and Anxiety Disorders by Lower Super Output Areas in Surrey 2022 Source: OHID Fingertips

Three of the LSOAs with the highest mood and anxiety disorder indicator scores lie within wards identified as being Key Neighbourhoods. Reigate and Banstead 008A and Reigate and Banstead 008B both lie within Hooley, Merstham & Netherne, Reigate and Banstead 008B lies within Tattenham Corner & Preston.

Self-Reported Wellbeing

The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) has developed three key indicators for self-reported wellbeing, including life satisfaction, happiness and anxiety. Self-reported wellbeing in Surrey was comparable to regional and national wellbeing 2020/21. Of Surrey residents, 5.3% reported a low life satisfaction score (6.1% Nationally), and 6.8% reported a low happiness score comparative to 9.2% nationally. Scores for high self-reported anxiety were observed in more of the population than the other wellbeing measures, 22.5%, slightly lower than that reported regionally 23.6% and nationally 24.2%.

Engagement is underway with priority places (as identified by the Health and Wellbeing Board) to measure wider health and wellbeing indicators. Findings will be published here as they become available, in early 2023.

QOF: Depression

Primary care Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF) data report the prevalence of depression, psychoses and dementia diagnosed in people registered with GPs. While covering most of the UK population, QOF data may not fully represent all groups and relies on accurate disease registers and diagnosis of mental health problems. We know through feedback from service users, that not everyone with common and/or severe mental illness is on their local QOF register. As a result, prevalence of health conditions represented by QOF data should be viewed with caution as a higher prevalence does not necessarily mean that the condition is genuinely more prevalent within that area but rather that the GP practices may be better at recording it.

Prevalence of depression recorded in the QOF register has risen rapidly over the past five years as can be seen in the Table 2 below. From 2014/15 to 2020/21 the prevalence of depression across England, the South East and Surrey has risen dramatically. Across England the prevalence has risen from 7.3% to 12.3%, an increase of 5.0%, Across the South East the prevalence has risen from 7.3% to 13.0%, an increase of 5.7%, and across Surrey the prevalence has risen from 6.2% to 11.1%, a rise of 4.9%.

| Area | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 |

| England | 7.3% | 8.3% | 9.1% | 9.9% | 10.7% | 11.6% | 12.3% |

| South East | 7.3% | 8.4% | 9.3% | 10.1% | 11.0% | 12.0% | 13.0% |

| Surrey | 6.2% | 7.2% | 8.3% | 8.9% | 9.7% | 10.4% | 11.1% |

Table 2. QOF registered Depression 2014/15-2020/21

The data visualisation shows that Surrey has a significantly lower prevalence of depression among adults aged 18+ than England (11.1% vs 12.3%) (2020/21). JSNA Mental Health Published Dashboard

Across Surrey local authorities in 2020/21, the prevalence of recorded depression ranges from the lowest value in Elmbridge of 9.8% to the highest in Waverley with 12.7%.

Long Term Mental Illness

Long term or chronic mental illness generally refers to mental ill health lasting greater than 12 months or with persistent life function limiting symptoms. Persons suffering from long term mental illness may find it hard to perform everyday tasks such as forming relationships, attending work, or completing household tasks. Different mental illnesses have different long-term effects. A Danish study found that the mental health condition that had the greatest Years Lived with Disability (YLD) was schizophrenia, followed by personality disorders for both males and females. The illnesses causing the third highest number of YLDs were anxiety disorders for females and Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) for males.

In the 2022 GP Patient Survey (GPPS), of those respondents registered with a GP in NHS Surrey Heartlands Integrated Care System, 9.1% reported having a long-term mental health condition. This is the lowest value in all ICSs across the South East commissioning region, and less than the England reported value of 12.3%.

QOF: Severe Mental Illness

SMI refers to mental health problems so significant, they impact a person’s functional ability as well as their ability to work, attend education or in other ways achieve their potential. The SMI register includes patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and other psychoses, and other people on lithium therapy. SMIs are further problematic because they are often associated with physical health problems (co-morbid) or co-exist with other mental or physical long-term problems or conditions (multimorbid). There are several NICE guidelines covering a range of conditions such as psychosis and schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, personality disorder or eating disorders. More detail on people in Surrey living with an SMI can be found in the JSNA Chapter on the Surrey Context.

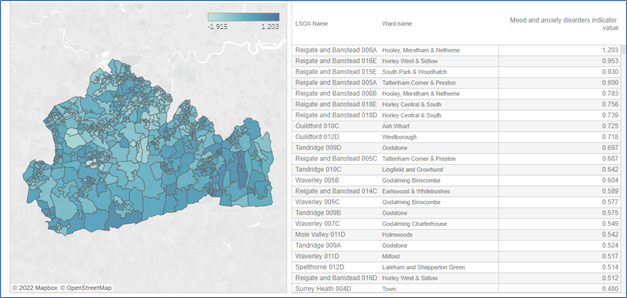

Proportion of count of comorbidities for SMI cohort and the comorbidity proportion.

Figure 3. Source: Population and Person Insights Dashboard, NHS England

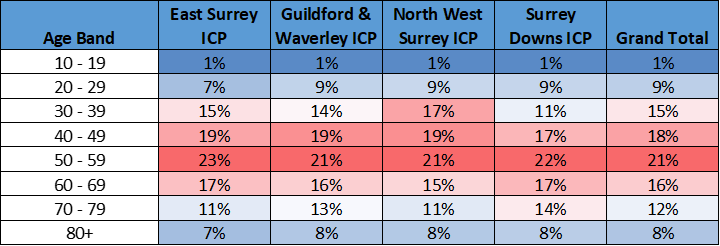

Total SMI Population by Age Band (% per Age Band in Place)

Table 3. Source: Surrey Heartlands NHS, Graphnet

In the last recorded data available (2020/21) Nationally by ICS area, Surrey Heartlands had significantly lower (the lowest) recorded (QOF schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other psychoses) Serious Mental Illness (all age). In 2020/21 0.87% (compared to 0.95% nationally) of people were on the SMI register for Surrey Heartlands ICB. This equals to approximately 8,417 individuals. A lower than national SMI prevalence was also observed in Frimley with 6,094 individuals registered 0.76% compared with 0.96% nationally. Across NHS Surrey Heartlands ICS there is a high level of variance in the prevalence of the above disorders at a Primary Care Network (PCN) level. In 2020/21 the PCN with the highest prevalence was Dorking PCN (0.94%), the PCN with the lowest prevalence was Woking Wise 1 PCN (0.58%). In 2019/20 Dorking PCN had the highest prevalence (0.94%) and Weybridge & Hersham PCN had the lowest (0.58%). However, the prevalence of SMI was 28% higher in the most deprived decile compared to the least deprived decile.

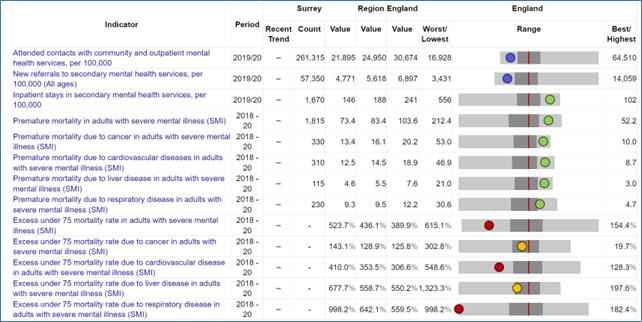

A report commissioned by Public Health England (PHE) found that people with an SMI die significantly younger than people without an SMI, and this is partly attributed to the co-occurrence of other long-term conditions. In Surrey (2019/20), these rates are significantly worse than England. The under 75 excess death rate in adults with an SMI is 523.7%. Similarly, there are worse rates in Surrey (compared to England) for under 75 excess death rates attributable to CVD (410%), cancer (143%), liver disease (677%) and respiratory disease (998%).

Figure 4. Serious Mental Illness in Surrey, South East and England Source: OHID Fingertips

In Surrey, (2019/20) there were 21,895 per 100,000 contacts with community and outpatient mental health services (compared to 30,674 per 100,000 in England). The rate of new referrals to secondary mental health services was 4,771 per 100,000 (compared to 6,897 per 100,000 in England). Some challenges found through engagement workshops by where there are no ways for people to be taken off the SMI register; and diagnoses given in secondary care are sometimes vague or given as suspected, which can cause confusion with admin teams leading to people being missed off the register.

In 2022 an independent review of SMI and Health Inequalities in Surrey was commissioned by Surrey Heartlands ICS.

In December 2022 SMI Physical Health Checks[1] (PHC) data shows that in Surrey Heartlands ICS 50% of people on the SMI register received their PHC in the last 12 months (NHSE PHC SMI 2022). As the national target is 60%, it key to understand what gaps there are in meeting this.

National findings suggest that there is a link between PHC uptake and deprivation (PHE SMI 2018). There is ongoing work both nationally and in Surrey to understand the physical and engagement barriers to PHC uptake. A previous piece of work done carrying out lived experience engagements in the region focussed on understanding engagement with PHCs. There were 5 main barriers identified:

- Perceived lack of quality follow-up support.

- Unaware of need for physical health check.

- Belief that a PHC would negatively impact mental health.

- Unable to arrange PHC appointment.

- Belief that a PHC would not positively impact physical health.

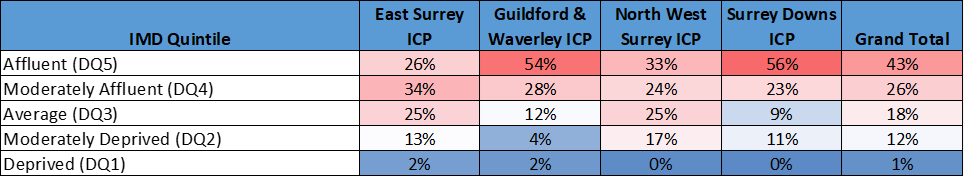

Total SMI Population by Deprivation Band (% per Deprivation Band in Place)

Table 4. Source: Surrey Heartlands NHS, Graphnet

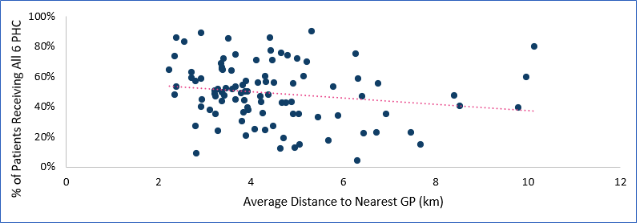

The report found a significant relationship between the distance to the nearest GP practice and PHC uptake. As can be seen from Figure 5, below, there is a negative relationship between the distance to the nearest GP and PHC uptake (correlation coefficient = -0.18). Regression analysis found that for every increase of 1 km in the average distance a patient lived to their GP practice, the percentage receiving a full PHC decreased by 2%. This is equivalent a decrease in 2 patients per GP practice. This means is that as distance to GP practice increase, the PHC uptake decreases

Distance to Nearest GP and PHC Uptake

Figure 5. Scatter graph of distance to nearest GP practice (Access to Healthy Assets and Hazards (AHAH[2])) and PHC uptake in Surrey, for GPs in Surrey.

There is national research to suggest that deprivation has a negative impact on mental health and SMI. In Surrey this is also the case. The effect of deprivation on SMI prevalence, as measured by the register size can clearly be seen. A decile comparison between areas scoring in the top 10% of deprivation IMD scores, when compared against areas in the bottom 10% of IMD scores shown a substantial difference.

This finding was further supported through engagements with service providers and lived.

A summary of the key findings of the report is copied below.

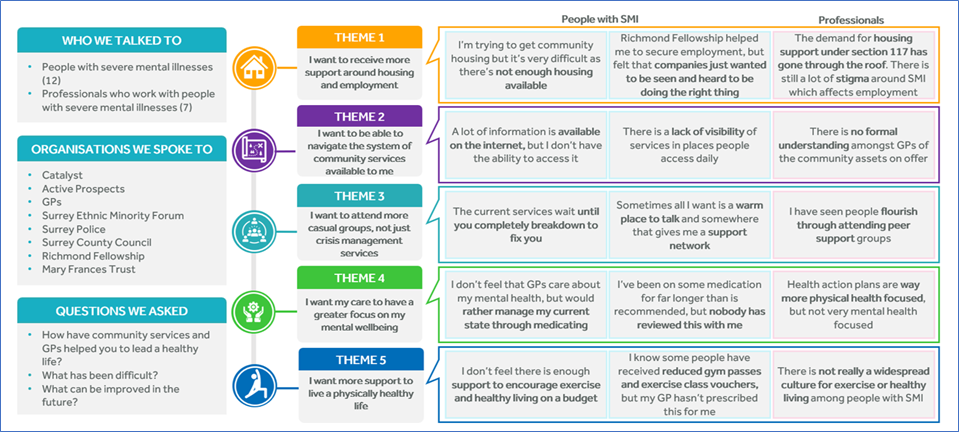

Figure 6. Engagement findings summary

Suicide and Injury Undetermined

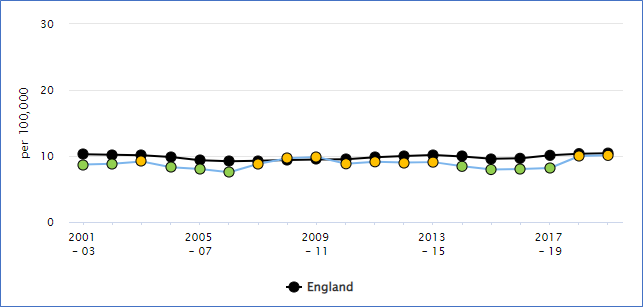

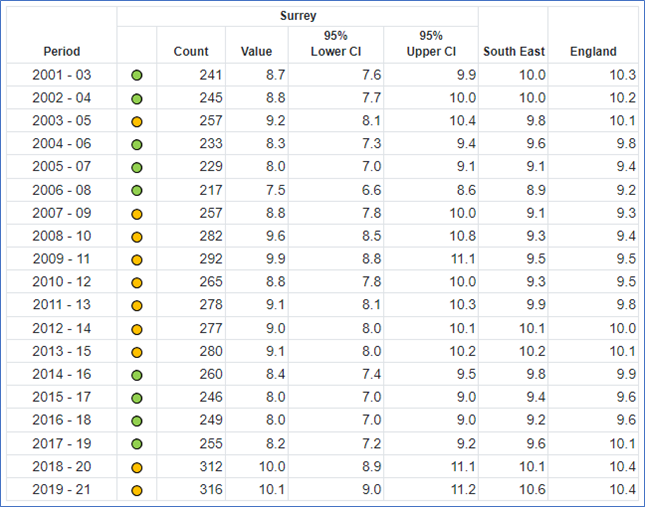

There has been a slight increase in the directly age-standardised suicide rate across both England and Surrey, comparing the three-year average in 2008/10 with 2018/20. The rate in Surrey grew from 9.6 to 10.0 per 100,000 and in England it grew from 9.4 to 10.4 per 100,000. For the period 2008/10 the rate was higher in Surrey than England. However, since 2009/11 the directly age standardised rate across Surrey has been below England’s (15). Given the low comparative prevalence of common mental disorders in Surrey it is surprising that suicide rate is only marginally lower than that observed nationally. This may be explained by historic data availability on CMD in Surrey and may indicate a change in prevalence. This requires further exploration.

The latest three-year average data (age standardised rate per 100 000) shows that:

- Surrey has the sixth lowest rate of suicide among its 15 Combined Intelligence for Population Health Action (CIPFA) nearest neighbours (CIPHA range: 8.4 – 14.3) (2018-20).

- The rate of suicide across Surrey was roughly 3 times higher in males than females (15.2 vs 5.1) (2018-20). Nationally there has been a reported increase in female suicides.

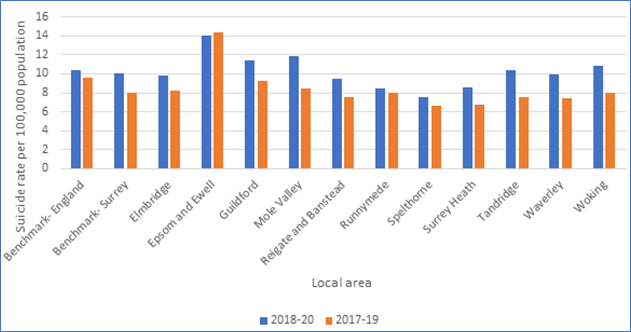

- The rate of suicide varied across Surrey local authorities with Epsom and Ewell having the highest rate of 14.0 per 100,000 and Spelthorne having the lowest rate 7.6 per 100,000 (2018-20).

Some key statistics relating to suicide within Surrey can be found below:

- The number of suicides in Surrey between 2018-20 was 312, an average of 104 per year and over 8 per month (2018/20).

- 74% of suicides were amongst Males (231) and 26% among Females (81) (2018-20).

Each suicide has far reaching consequences, affecting a number of people directly and many others indirectly, and with those affected often impacted economically, psychologically and spiritually. Family, friends, and carers of those who die by suicide have a 1 in 10 risk of making a suicide attempt after experiencing loss.

Suicide is often the end point of a complex history of risk factors and distressing events. The prevention of suicide strategies have to address this complexity. As there is no single risk factor for suicide, the prevention of suicide does not sit with any single organisation.

Suicide rate – Surrey and England

Figure 7. Suicide rate (Persons) Directly standardised rate – per 100,000 Source: OHID Fingertips

Suicide rate – Surrey, South East and England

Table 5. Suicide rate (Persons) Directly standardised rate – per 100,000 Source: OHID Fingertips

Over the last 20 years the suicide rate in Surrey has been between 8- 10 per 100,000 of population. During the 2008-2010 financial recession the suicide rate in Surrey increased and this was a pattern also seen in England. Recession increases the risk factors for poor mental health. Therefore, if England again enters a recession, it is expected that the suicide rate in Surrey would increase.

Suicide rate – England, Surrey, District & Boroughs

Figure 8. Comparison Suicide rate, all persons in Surrey 2017- 2020

In 2021 an audit of the Surrey Coroner’s Records of Deaths identified as Suicides was completed for death in 2017- 2020. This covered four calendar years and cases that had a completed inquest. Between 2017 and 2021 there were 258 deaths by suicide in Surrey. In 2021 Surrey Public Health Team commissioned a suicide audit. Coroners’ files were reviewed to understand the key contributing risks to suicide, access to services and opportunities for suicide prevention.

In Surrey, a quarter (28%) of people visited a GP in the three months prior to death. The reasons for the visit varied between a mental health issue, a physical issue, both issues and/or just a routine appointment. 71% of people who died by suicide in Surrey identified as White British. The mean age at death was 53 for males and 41 for females (48.2 overall), with the highest number of deaths, one third, in the 45-59 years age bracket.

36% of people who died lived alone, and 36% were not in a long-term relationship of any sort. Approximately a quarter (27%) of Surrey residents live alone according to the 2011 census.

Nationally it is estimated that around one third of those who die by suicide in England have been in contact with mental health services in the 12 months leading up to their death, a further third have seen their GP but are not receiving specialist mental health support (Department of Health, 2017). In Surrey a quarter of individuals who died by suicide were in contact with a mental health service at the time of their death.

By far the most common mental health condition that individuals had who died by suicide was depression. Over half had either a clinical diagnosis of depression or had documented in their clinical notes that episodic periods had occurred over their lifetime. A third had an anxiety condition.

The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health, Social and Clinical Characteristics of Mental Health Patients Dying by Suicide in the UK shows the main social features of patients dying by suicide in the UK. There were high rates of social adversity and isolation. 53% of patients had a comorbid diagnosis. 64% of patients had a history of self-harm. 47% of patients had a history of alcohol use and 27% had drug use

Self-harm (including attempted suicide) is the single biggest indicator of suicide risk and approximately 50 per cent of people who have died by suicide have a history of self-harm (Department of Health, 2017).

Although the circumstances of every death are unique, through the audit we can begin to see factors in common across the cases, the key contributing factors mentioned in the notes were:

- 50% – Mental illness

- 32% – Relationship problems

- 19% – Bereavement

People born in the 1960s and 1970s are known as Generation X. Now in their 40s and 50s they are dying in greater numbers by suicide or drug poisoning than any other age group. Research shows that Generation X show poorer physical health, increased rates of depression and anxiety, and higher levels of unhealthy behaviours, such as alcohol use and smoking, compared to previous generation.

Compared with people who have been bereaved through other causes, individuals who are coping with a loss from suicide are more likely to experience increased risk of psychiatric admission, depression, and grief beyond 6-12 months of bereavement which severely disrupts the person’s ability to carry out normal activities such as work, relationships, and social functioning. Estimates vary on how many people are affected by each suicide – ranging from six to 60 people. A conservative estimate of 10 people directly affected by each of these deaths suggests almost 50,000 people annually in England could benefit from support after suicide. In Surrey around 920 people could benefit from support in one year, although it is unlikely that all people bereaved by suicide would come forward for support. Some may feel that they do not need support, others may feel concerned about the stigma of suicide.

Eating Disorders

The Health Survey for England 2019 Eating Disorders report found that adults who screened positive for a potential eating disorder were more likely than others to have consulted their GP for a mental health, nervous or emotional problem (24%, compared with 10%). They were also more likely to have received counselling or therapy (16%, compared with 7%).

Why are eating disorders important?

Approximately 1.25 million people in the UK have an eating disorder. It is estimated that between 10% and 25% of those with an eating disorder are men. Most eating disorders develop during the late teens to the mid-twenties. However, it is not uncommon for eating disorders to affect people of all ages.

Having an eating disorder is linked to long term health implications including obesity, poor functioning of the body, infertility, stunted growth, brittle bones, damage to internal organs and low levels of essential vitamins. Having an eating disorder can also manifest psychologically including sleep problems, difficulty concentrating, feeling down, loss of interest in others and obsessive behaviours. It is common that eating disorders can occur alongside mental health conditions such as depression, personality disorders and substance abuse. Often an eating disorder is one of several conditions that is having a significant impact upon individuals and their quality of life.

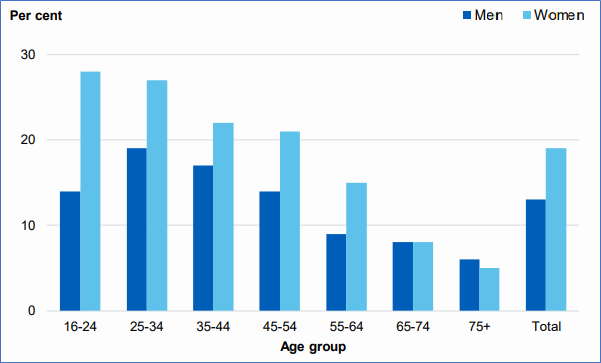

Figure 9: Screened positive for possible eating disorder in past year, by age and sex. Men Women Source: Health Survey for England 2019 Eating Disorders, NHS Digital Source: NHS Digital Base: Aged 16 and over

5. Prevention and Protection of Emotional and Mental Wellbeing

It is known that those living in areas of deprivation and or impacted by socio-economic and environmental inequalities are at greater risk of poor mental health. There is a complex interplay between socio-economic and environmental inequalities, those living in deprivation and their mental health status, each being a possible cause or consequence. Often these same groups of people have less access to effective and relevant support for their mental health, and if they do get support, their experience and outcomes are often poorer. A lack of access to resources such as adequate housing and exposure to negative stressors such as violence, crime or lack of public green space are significant contributors.

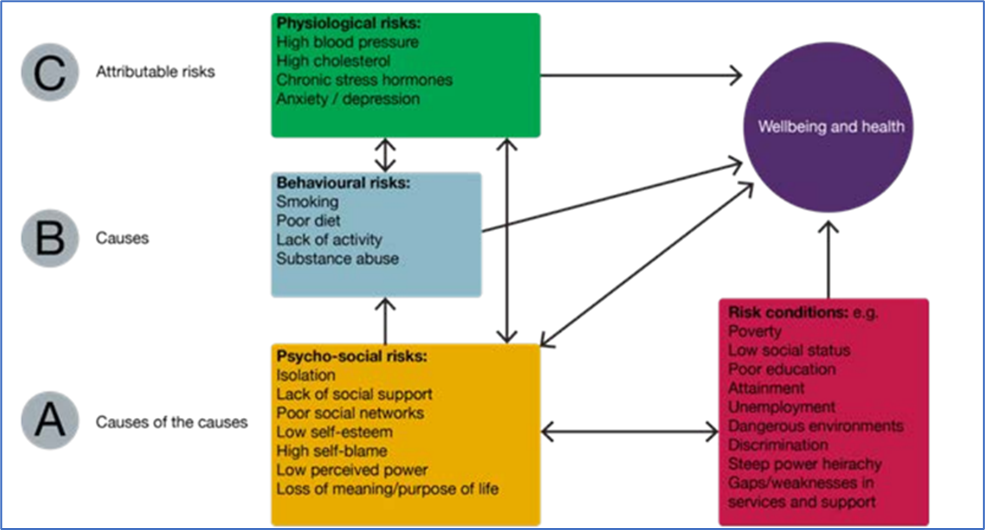

Pattern of risks affecting health and wellbeing

Figure 10. Source: PHE, Reducing health inequalities: system, scale and sustainability

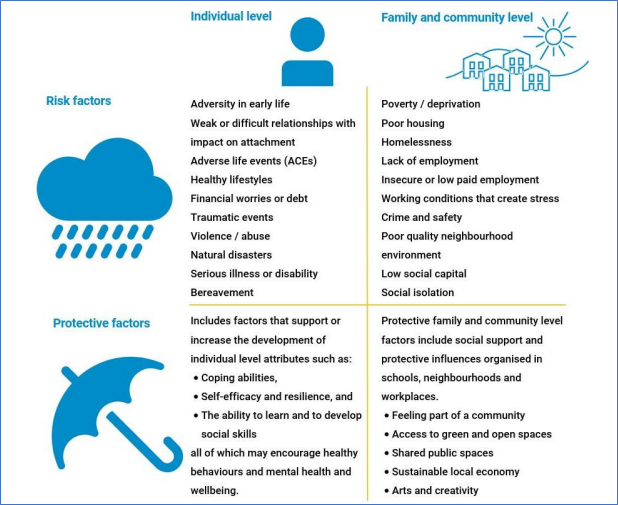

Risk and protective factors at individual and community level are illustrated below.

Common risk and protective factors for mental wellbeing at individual and family/community level

Figure 11. Source: OHID, Disparities Mental health JSNA toolkit, prototype Mental, Health tool and The Mental Health Wellbeing Impact Assessment Toolkit

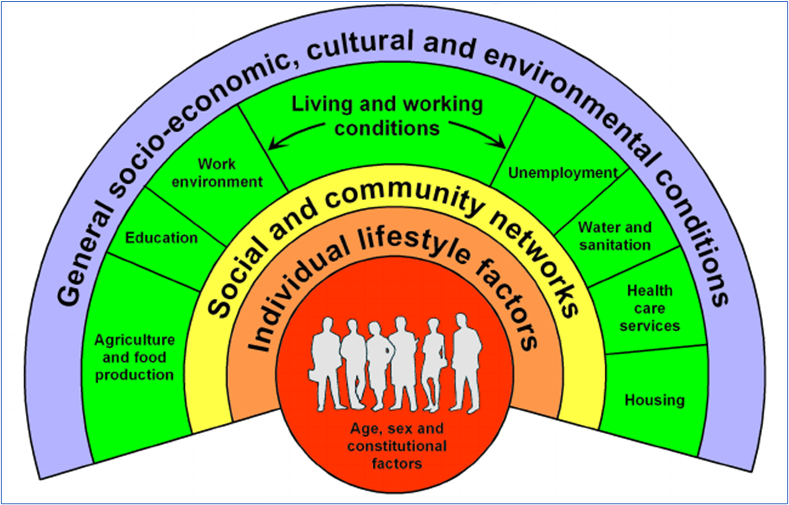

The Dahlgren and Whitehead Model provides a useful framework to consider these risk factors and conditions and will be applied to the structure of this chapter.

Figure 12. Dahlgren & Whitehead Model of the Health Determinants

Socio-economic, Cultural and Environmental conditions: The Current Context

Cost of Living Crisis

Recently, there has been an increase in the rates of people experiencing food insecurity, this is now estimated at 4.7 million across the UK (Kings Fund 2022). Other wider factors such as increase in energy prices, combined with rising inflation, stagnant wages and uncertainty about benefits further lead to an increase in people living with food insecurity or fuel poverty. These factors combined with the uncertainty can cause considerable anxiety. People already experiencing poor mental health (for example those living with an SMI) or living with a disability are more likely to be affected. In addition, the uncertainty of the benefits system, and the negative emotions such as stigma associated with accessing food banks further lead to poor mental health. Fuel poverty has been found to correlate with a variety of well-being outcomes, even when controlling for lifestyle factors. Two thirds of therapists in a national survey say cost of living concerns are causing a decline in people’s mental health. British Medical Journal research says that the surge in prices over recent months is exacerbating insecurity and harming people’s mental health

Another issue related to financial uncertainty is debt; debt is significantly linked to poor mental health. Those with problem debt are three times more likely to consider suicide. Around 60% of those who had 3 or more debts experienced mental health problems. Research has found that multidisciplinary interventions are successful if they aimed at improving social circumstances for individuals with mental health problems (including employment, education, and social isolation).

The Health and Wellbeing Board has identified 21 priority areas across Surrey where substantial opportunities for population-wide health and wellbeing improvements exist. We know poverty and its associated effects are a key health and wellbeing risk factor, so the importance of understanding these communities has only become more acute as a result of the rising cost of living.

There are already a lot of health and wellbeing interventions active in these communities. Surrey County Council will be undertaking mixed methods research in early 2023 to better understand health and wellbeing issues in these communities as well as understand what assets they define as valuable. This will help us develop a measure for healthy and thriving neighbourhoods to help us focus our resources on what will have the most impact.

The specific aims of the project are:

- To measure how those living in priority areas in Surrey feel about their neighbourhoods, using ‘meaningful’, predefined metrics co-designed with residents and other stakeholders.

- To understand what it is like to live in five of the priority areas in Surrey, and how the cost-of-living crisis is impacting this.

- To understand whether the needs and ambitions of the neighbourhoods are being met by the current programmes of work, including emergency interventions that have been implemented.

As findings become available, they will be published here.

COVID-19

The first case of Coronavirus Disease – 19 (COVID-19) recorded in the United Kingdom (UK) was on January 29th 2020. On March 23rd 2020 the Prime Minister announced the first nationwide lockdown ordering people to ‘stay at home’. During 2021-21, the UK would enter numerous nationwide lockdowns along with several more localised lockdowns. The lockdowns imposed bans on nearly all social gatherings, encouraged people to work from home and to practice social distancing whenever possible. The nature of the laws enacted meant that the population’s lives were impacted on a multitude of levels of which many related to a person’s mental wellbeing.

Throughout the pandemic there was greatly increased pressure on the NHS which led to many routine operations being either delayed or cancelled. There was also a move towards digital and socially distanced appointments. All of this had knock-on effects of the levels of and access to care received by patients across the UK.

Several studies into the effects of COVID-19 on mental health have been carried out, three of which have been used to guide this report. Overviews of each study are in Table 6 below.

| Study | Summary |

| Mind, a UK-based mental health charity, carried out two surveys of nearly 12,000 UK residents at both the start and one year into the COVID-19 pandemic. | The survey sought to understand how the lockdowns and changes associated with COVID-19 had affected people’s mental health |

| ‘Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts’ (6). Two cohorts were reviewed in this paper, one comprising of Scottish residents and the other, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), focused on parents and their children (13-24 year olds) residing in Avon, South West England. | Avon was a previous unitary authority that split into four further local authorities, one of which, Gloucestershire is a Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy CIPFA nearest neighbour to Surrey. Results from the ALSPAC study are quoted due to the greater similarity with Surrey. |

| GOV COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance: report | Throughout the pandemic, the UK Government published the ‘COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance report’, a high-level summary of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the mental health and wellbeing of the population in England. It compiles routinely updated indicators from multiple sources and summarises important recent findings from a pre-defined set of studies. It broadly covers three key areas: ‘Important findings’, ‘Measure of anxiety, depression, loneliness and life satisfaction’ and ‘Children and young people’ |

| COVID-19 Impact on Mental Health Service Users Surrey: Rapid Needs Assessment | Qualitative insights into service users in Surrey’s experience of the pandemic and impact on mental health. |

Table 6. Studies into the effects of COVID-19 on mental health

The findings in Table 7 below, highlight a population level decrease in overall wellbeing especially in geographies of greatest need.

| Key Themes | Summary |

| Over the course of the pandemic mental health burden varied. | From April 2019 to April 2020 the proportion of adults over 18 reporting clinically significant levels of psychological distress increased from 20.8% to 29.5%. This number had fallen to 21.3% by September 2020, by January 2021 it was back at 27.1% and by March 2021 it fell again 24.5%. |

| People who already struggled with mental health issues before the pandemic experienced the greatest impact on mental health. | This could be a particular issue for areas of Surrey with higher prevalence of Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, and other Psychoses; as observed in Dorking PCN, which had the highest QOF registered incidence in FY 2019/20. |

| COVID-19 has heightened inequality | COVID-19has heightened inequalities in mental health such as the association of higher levels of deprivation with increased mental health burden. This could lead to negative outcomes for persons living in the key neighbourhoods outlined in the Surrey Health and Wellbeing strategy 2022. |

| Young people (13-24) are finding it hard to cope | Young people who are struggling with their mental health are more likely to use unhealthy coping strategies such as self-harm than adults. This could be a particular problem in Guildford, which has the highest population of 13–24 year-olds across Surrey District & Boroughs. |

| Cohorts/sub-populations | Aside from the overall trends in mental health mentioned above, the three studies highlighted several key populations that suffered to different extents during the pandemic. The below text aims to highlight these inequalities. |

| Gender | It was found that females were more likely to experience depression or anxiety during the COVID pandemic than males. A possible reason is that women are more like to have family and caring responsibilities, which required large adjustments over the course of the pandemic, particularly to manage housework and childcare during lockdowns. Woldingham in Tandridge has the highest proportion of females in Surrey and is the only ward where this proportion is over 55%. |

| Age | Age is a complicated factor with respect to its impact on mental health during the pandemic with several studies reporting different conclusions, some of which are summarised below. The prevalence of probable depression during the pandemic was highest for younger individuals (18-40 year-olds) and decreased with older age. Young adults (18-30 year olds) with a pre-existing risk of experiencing loneliness are now at even greater risk of experiencing loneliness. Being a university student had a potential link to increased risk of loneliness. This could be a particular issue within the Guildford Borough which has the highest proportion of young adults across Surrey and is home to three universities. Amongst older adults, being asked to shield was associated with increased levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness. |

| Ethnicity | Linking ethnicity with mental health outcomes directly during the pandemic has proved difficult. Associations between ethnicity and mental health are influenced by many variables such as employment and income protection, community, gender and deprivation which may have greater influence. Most studies conducted so far do not have enough representation of minority groups to produce any meaningful insight. |

| Employment and Income | The three studies reviewed found that a person’s employment and income are strong predictors of someone’s mental health outcomes during the pandemic. Unemployment and lower household income have been linked to higher levels of psychological distress, anxiety, depression and loneliness, and lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction during the pandemic. Runnymede and Woking districts and boroughs have the lowest levels of employment in Surrey amongst 16-64 year olds (74.7% & 74.9% respectively), therefore problems with mental health may be more pronounced in these areas. |

| Urbanisation | There has been conflicting research on the how living in an urban versus rural location effected mental health during the pandemic. One study reported adults living in urban areas reported worse and increasing loneliness. However, another found no evidence of a difference in depression and anxiety between rural and urban areas. Out of the eleven District & Boroughs in Surrey, only Mole Valley and Tandridge are classified as ‘urban with significant rural’ and Waverley as ‘Largely rural’, while the rest are classified as either ‘Urban with major conurbation’ or ‘Urban with city and town’. The differing levels of urbanisation across the county could have had an impact on the prevalence of mental health problems during the pandemic. Another study found that ‘Between April and June 2020 levels of hedonic (feeling good) and evaluative (life satisfaction) wellbeing decreased. However, for those living in more deprived neighbourhoods the level of hedonic wellbeing decreased more than for those living in more affluent areas.’ The effect that local area deprivation has on mental health would have been a particular issue for the 21 key neighbourhoods outlined in the Surrey HWB Strategy. |

| Long Term Conditions | It was found that ‘during the pandemic, adults with long term physical health conditions reported worse levels of depressive symptoms than adults without long term physical health conditions.’ Summaries of specific research findings are below. Having asthma increased the likelihood the person would suffer with anxiety or depression during the pandemic. There was an increased risk of depression in adults that suffer with breast, prostate, or blood cancer but not other types of cancer. Having a long-term physical health condition was associated with worse levels of depressive symptoms. |

| Referrals to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) | For the first time in 2020/21 both the number of referrals and referrals starting treatment fell for IAPT, this could either be due to fewer patient presenting at their GP or fewer referrals being made following appointments. During this year, the system failed to meet its target of delivering timely access to at least 15% of the community prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders. This creates pressure for more referrals and appoints to be delivered if the target it to be met over the coming years. The number of referrals to the IAPT programme across England fell from 133,191 in April 2019 to just 57,814 in April 2020, the number of referrals to secondary mental health, learning disabilities and autism services fell from 303,373 in April 2019 to 208,829. This drop was short lived, by July 2020 the referrals to IAPT where at 128,988 and referrals to secondary mental health, learning disabilities and autism services where at 339,522. |

Table 7. Decrease in overall wellbeing

Climate Change

The Independent Assessment of UK Climate Risk (2021) and the government’s UK Climate Change Risk Assessment (2022) shows that the UK faces risks from climate change to its natural environment, food, water supplies, infrastructure and the health and wellbeing of its population. The Adaptation Sub-Committee of the Committee on Climate Change (2017) commissioned regional assessments of climate change risk. Risks were identified for the South East of England region until 2050 including risks of impacts on residents’ wellbeing from disruption to health, social care and emergency management services and school provision, from flooding, heatwaves and storms and excess deaths and illness from overheating.

Surrey’s Climate Change Strategy (2020) recognises that Surrey faces an increased frequency and severity of adverse weather events, notably flooding and heatwaves. These severe weather events have the potential to have a significant impact on local services and infrastructure such as highways, and to the health and wellbeing of residents, particularly those in vulnerable groups.

Data lacks to show how Surrey residents’ emotional and mental wellbeing is impacted by the experienced climate. Existing population vulnerabilities may be exacerbated by climate hazards and long-term climate risks, resulting in increased inequities. The effects of climate change have considerable implications for mental health, wellbeing and required service provision.

Figure 13. The health threats resulting from current and anticipated climate change impacts Source: Imperial College London, Grantham Institute briefing paper no. 36 (May 2021)

Social Media

Social media presents a modern challenge to enhanced mental and emotional wellbeing. Social media on one hand enables instantaneous connectivity with friends and families anywhere in the world. On the other, social media, driven by algorithms for continuous benchmarking success on comparison to others which is known to cause anxiety and have a negative impact on mental health. The negative impact of social media has been observed primarily in Children and young People and will be explored thoroughly in the JSNA Children and Young People emotional wellbeing chapter.

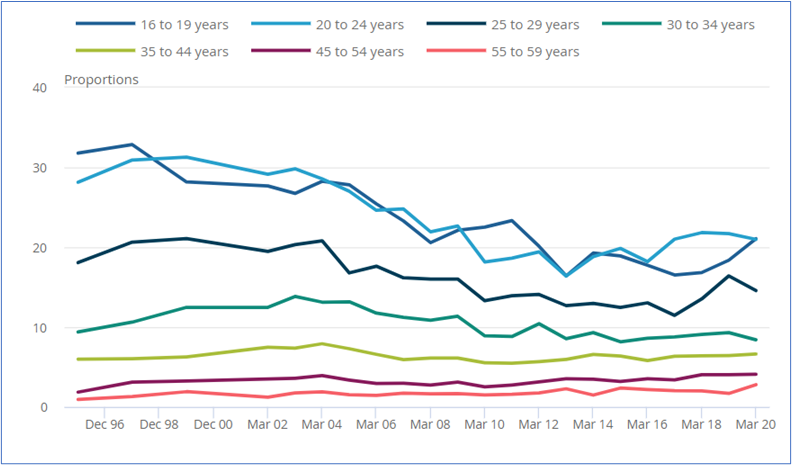

Who accesses social networking websites and apps?

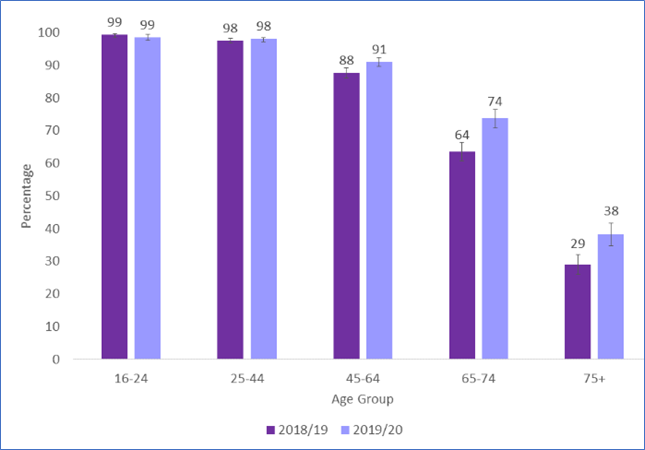

Figure 14. Reported frequency of using social networking websites or apps by age, 2018/19 – 2019/20 Source: National Statistics, Social Networking – Taking Part Survey 2019/20 dated 16 Sep 2020

In the Social Networking – Taking Part Survey 2019/20, 80% of adults reported using social media every day, whilst just 2 percent said that they used it less than once a month. The use of social media is highest in the 16 to 44 age band at 99% dropping to 38% for 65+. There are only small insignificant differences of use between genders and those in different Indexes of multiple deprivation.

The rapid growth and use of social media has had both negative and positive impacts on mental health. There have been some suicides in England where the use of social media has been identified as a contributing risk factor. The Online Safety Bill is proposed legislation in the UK Parliament intended to improve internet safety. The Bill would create a new duty of care for online platforms towards their users, requiring them to act against both illegal and legal but harmful content. At the time of writing this report the Online Safety Bill was at the House of Commons stage and was yet to pass through the House of Lords.

Deprivation

More detail is available in the Surrey Context: IMD and Healthy Life expectancy at birth.

The Indices of Multiple Deprivation are a unique measure of relative deprivation at a small local area level (Lower-layer Super Output Areas). The Surrey place tableau dashboard shows that the majority (68.5%) of Lower Super Output Areas (LSOA) in Surrey are in in the least deprived deciles 8, 9 and 10. There are no Surrey LSOAs in decile 1 of the overall Index of Multiple Deprivation, and just 4 (0.6% of areas) in decile 2. These are parts of Westborough and Stoke wards (in Guildford), Hooley, Merstham and Netherne ward (Reigate & Banstead) and Canalside ward (Woking). Surrey has a population of contrast with large populations representing the most affluent deciles. Populations with large differences in wealth and resource between individuals are associated with higher levels of poor health and mental health problems.

Air Quality

More detail is available in Surrey Context: Pollution and Air Quality

In Surrey the fraction of mortality attributable to particulate air pollution (new method) was 6.2% in 2020, which is higher than the South East at 6.0% and England’s average at 5.6%. Data does not show the attributing factors for the mortality rates and there is a close link between poor physical and poor mental health. Despite the complex link between cause and consequence for physical and mental health, evidence suggests that air quality can adversely affect the brain and increase risk for psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and depression and increase the use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines. One study in South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust shows that continual exposure to air pollution (assuming causality) has also been associated with increased mental health service use amongst those recently diagnosed with psychotic and mood disorders. Air pollution can also contribute to a decline in mental ability and vascular dementia in older people.

Local data exploring this link is not available, therefore, exploration of the link between air quality and the impacts of this on Surrey’s residents’ mental health is now required.

Living and Working Conditions

Housing

The importance of safe and settled accommodation is well documented as a determinant of good mental health and wellbeing. Public Health England’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (2019) and the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (2016) outline that housing is critical to the prevention of mental health problems and the promotion of recovery.

Insecure, poor-quality housing and overcrowding can cause a decline in an individual’s mental wellbeing with 19% of adults living in poor quality housing in England having poor mental health outcomes. This includes those living in hostels, shelters, refugees, unsuitable accommodation, and those sofa surfing. It is known that 3.43% of Surrey’s population lives in overcrowded accommodation, that is, they had fewer bedrooms than they needed to avoid undesirable sharing, which is similar to that of the South East Region.

The impact of housing is also important to consider in forward planning as a preventative factor against poor mental health, as it is known to impact on wellbeing for children and young people and consequently for future generations.

See fuel poverty section below for more information regarding how cold homes impact mental health.

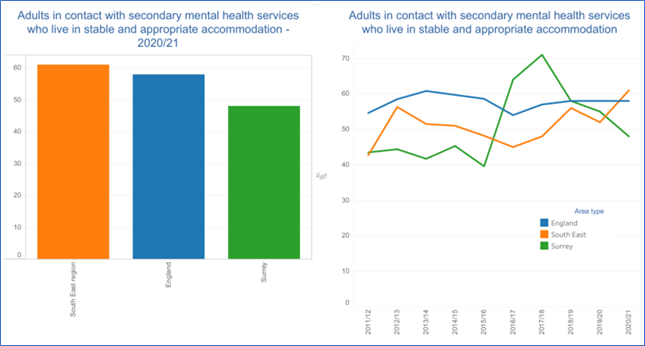

Stable, good quality housing is a protective factor against poor mental health and vital for recovery. In Surrey (2020/21), less than half (48%) of adults who are in contact with secondary mental health services live in stable and appropriate accommodation compared to over 60% nationally. Over half of mental health service users lack housing security which could negatively impact their recovery journey. The data illustration shows how stable accommodation in 2020/21 had declined significantly since 2017/18.

Stable accommodation

Figure 15. Adults in Contact with Mental Health Services who live in stable accommodation Source: Mental Health Tableau Dashboard

There is anecdotal evidence from the frontline in Surrey that the absence of stable housing options in Surrey delays hospital discharges. In turn, there is an absence of escalation pathways to support housing officers to refer people back to secondary care services when required, which may have detrimental effects on recovery.

People open to an Adult Social Care Mental Health Team in Surrey as a service user, excluding unknown addresses and under 18s, by Accommodation Status

| Area | Not known | Settled | Unsettled | Grand Total |

| Elmbridge | 36 | 150 | 16 | 202 |

| Epsom and Ewell | 25 | 92 | 21 | 138 |

| Guildford | 48 | 180 | 42 | 270 |

| Mole Valley | 37 | 102 | 16 | 155 |

| Reigate and Banstead | 57 | 205 | 63 | 325 |

| Runnymede | 37 | 62 | 6 | 105 |

| Spelthorne | 42 | 97 | 26 | 165 |

| Surrey Heath | 23 | 97 | 18 | 138 |

| Tandridge | 20* | 64 | <5 | 88 |

| Waverley | 33 | 135 | 22 | 190 |

| Woking | 69 | 144 | 24 | 237 |

| Out of County | 29 | 109 | 76 | 214 |

| Grand Total | 2,227 |

Table 8. Accommodation status Source: SCC ASC

Fuel Poverty

Overall, Surrey had smaller proportions of households in fuel poverty (6.9%) than the English average (13.2%) in 2020. Guildford had the highest proportion of households in fuel poverty at 7.9% alongside Waverley and Epsom & Ewell with 7.3% in fuel poverty. Surrey Heath had the smallest percentage of households in fuel poverty at 5.8%. (Source: Fuel Poverty & related statistics, Surrey-i)

Mortgage and Landlord Possession

The Ministry of Justice produces quarterly national reports on mortgage and landlord possession.

| Mortgage claims, orders, warrants and repossessions have increased significantly when compared to the same quarter in 2021. | Compared to the same quarter in 2021, mortgage possession claims increased from 2,570 to 3,160 (23%), orders from 1,650 to 2,482 (50%), warrants from 1,121 to 2,112 (88%) and repossessions by county court bailiffs increased from 313 to 733 (134%). |

| Landlord possession actions have all increased significantly. | The pattern is repeated for landlord possession actions. When compared to the same quarter in 2021, landlord possession claims increased from 14,436 to 20,460 (42%), orders from 6,865 to 16,158 (135%), warrants from 4,285 to 8,717 (103%) and repossessions from 2,729 to 5,409 (98%). |

Table 9. Source: National statistics, Mortgage and landlord possession statistics: October to December 2022

Published 9 February 2023

Quarterly data is available by District & Boroughs councils with the use of webtool Mortgage and Landlord Possession Statistics: data visualisation tool.

Homelessness

More detail is available in Surrey Context’s chapter relating to homelessness.

Poor mental health is both a cause and consequence of homelessness. Those who are homeless are known to be at an increased risk of poor mental health outcomes, when compared to the general population. In the UK 45% of people experiencing homelessness have been diagnosed with a mental health issue. This is increased further for those caught in the ‘revolving door’, between hostels, prison, hospitals and the streets. Compared with the general population, homeless people are twice as likely to have a common mental health condition, and psychosis is up to 15 times more prevalent. They are also over nine times more likely to complete suicide. People experiencing homelessness find it difficult to access health services, including mental health care.

The 2016 Surrey Homeless Health Needs Audit highlighted that locally approximately 76% of respondents had at one time been told by a doctor or health professional that they suffer from depression, with the majority having been diagnosed in the previous 12 months. The audit also highlighted the clustering of factors that often occurs alongside homelessness and mental health as 40% indicated they used alcohol and/or drugs as a coping mechanism. In relation to access, 33% of respondents indicated that there was at least one occasion when they felt they needed an assessment or treatment for mental health but didn’t get it. The main reasons given for this varied from their own substance misuse, simply not being able to get an appointment or being on the waiting list.

Community Safety and Feeling Safe

Perceived safety or feeling safe in the community is central to wellbeing. Evidence highlights the physiological response to the stressor and coping behaviours have a detrimental impact on both mental and physical health. Surrey County Council is developing a survey linked to the new resident’s survey. Findings are to be added here when available.

Domestic Abuse

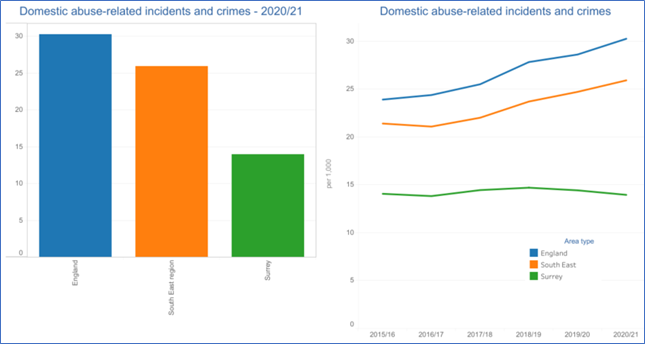

Being a victim of intimate partner violence or domestic abuse increases the risk of mental health problems and there are high rates of mental health conditions (particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)) among people who have been raped and among immigrant women who have undergone female genital mutilation.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that 1.2 million women and 700,000 men experience domestic violence. The rate of domestic abuse related incidents and crime in Surrey is 14.0 (per 1000), compared to 25.9 in the South East region and 30.3 in England. Other indicators are the rate of children on protection plans, 33.7 (per 10,000) in Surrey, compared to 25.9 in the region and 41.4 in England. These data only relate to official reports of violence, so real figures of domestic abuse are likely to be much higher. Research suggests that women experiencing domestic abuse are more likely to experience mental health problems, and conversely women with mental health problems are more likely to be victims of abuse. A systematic review found correlations between domestic violence and depression, anxiety PTSD, and substance use. Children exposed to domestic violence are more likely to have poorer educational outcomes and higher levels of mental ill health.

Domestic abuse-related incidents and crimes

Figure 16. Domestic abuse-related incidents and crimes – 2020/21Source: Mental Health Tableau Dashboard

Violent Crime Offences

More detail is available in the JSNA Chapter Community Safety.

Surrey is among the top 5 safest counties in England. The overall crime rate in Surrey in 2021 was 49 crimes per 1,000 people, and the most common crimes were violence and sexual offences, experienced by 20 out of 1,000 residents. Hospitalisations due to violent crime (including sexual violence) are experienced by 25.8 per 100,000 in Surrey, compared to 29.4 in the South East region and 41.9 in England. In Surrey, the highest rate is in Reigate and Banstead (34.6 per 100,000), and the lowest in Runnymede (17.1 per 100,000).

There is high prevalence of mental health needs among people in contact with the criminal justice system. 16% of prisoners report symptoms indicative of psychosis, a much higher proportion than in the general population. These disorders are more severe and complex and are often combined with poor physical health and substance misuse. There are high levels of mental health conditions amongst people on probation and among male gang members.

People in contact with the criminal justice system have substantially more risk factors for suicide (increased prevalence of mental health conditions, substance misuse and socioeconomic deprivation) and are recognised as a priority group in the cross-government suicide prevention strategy. The risk of suicide is highest in the 28 days following release from prison.

Many people in contact with justice services with mental health problems will additionally be experiencing other issues such as difficulty accessing good quality homes, employment and income. This may result in their mental health deteriorating. Many have been victims of abuse and crime themselves.

Being a victim of crime, or exposure to violent or unsafe environments can increase the risk of developing a mental health problem. The most serious example at a young age is child abuse, which can have a sustained detrimental effect on mental health through to adulthood.

Workplace and Employment

Unemployment

The ONS review of labour markets identify 2.6% unemployed in Surrey comparative to 3.3% in the South -East and 3.8% in England for the period July 2021 – June 2022. In October 2022, 2.1% (15,505) of Surrey residents were claiming job seekers allowance in comparison to 2.9% South East and 3.6% Nationally. Surrey has the third lowest rate of Employment Support Allowance claimants for mental and behavioural health disorders (2019) among its CIPHA comparable areas in the South East of England (16.4 per thousand which is significantly lower than the 20.4 average for comparable areas and 27.3 for England).

The percentage of the population with physical or mental long-term conditions in employment (2021/22) (aged 16-64) was 74.5% in Surrey, comparably higher than the South East, 70% and England 65.5%. It is important to note that this information is Surrey-wide and may mask pockets of high unemployment rates.

Workplace Stress and Burnout

Work-related stress, depression or anxiety is defined as a harmful reaction people have to undue pressures and demands placed on them at work. The Health and Safety Executive report on work related stress, anxiety and depression statistics in Great Britain (2021) cites that the main work factors cited by respondents as causing work-related stress, depression or anxiety were: workload pressures, including tight deadlines and too much responsibility and a lack of managerial support.

By industry sectors, stress, depression, or anxiety is most prevalent in (in descending order):

- Public administration, defence, compulsory social security

- Human health and social work activities

- Education

Although there is no Surrey data, the latest national Labour Force Survey (2020-21) data shows that:

- Stress, depression, or anxiety accounted for 50% of all work-related ill health cases.

- 822,000 workers were suffering from work-related stress, depression, or anxiety (new or long-standing), a prevalence rate of 2,480 per 100,000 workers. Of this total, an estimated 449,000 reported that this was caused or made worse by the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic.

- In 2020/21 the rate was higher than the 2018/19 pre-coronavirus levels.

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) data shows that stress, depression or anxiety and musculoskeletal disorders accounted for the majority of days lost due to work-related ill health in 2021/22. 17.0 million days were lost for stress, depression or anxiety and 7.3 million days were lost due to musculoskeletal disorders.

- On average, each person suffering took around 21.6 days for stress, depression, or anxiety.

National suicide prevention policy advises consideration of unskilled manual workers and health and social care workforce.

Number of Surrey enterprises by group.

| Industry Group | England | South East | Surrey | |||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | |

| Agriculture, forestry & fishing | 93,195 | 3.9% | 11,095 | 2.7% | 825 | 1.3% |

| Production | 131,765 | 5.5% | 20,750 | 5.0% | 2,420 | 3.8% |

| Construction | 327,615 | 13.6% | 61,355 | 14.9% | 8,890 | 14.0% |

| Motor trades | 69,475 | 2.9% | 11,570 | 2.8% | 1,555 | 2.4% |

| Wholesale | 96,705 | 4.0% | 14,860 | 3.6% | 2,165 | 3.4% |

| Retail | 195,395 | 8.1% | 30,245 | 7.3% | 3,730 | 5.9% |

| Transport & Storage (inc. postal) | 122,265 | 5.1% | 16,290 | 3.9% | 1,820 | 2.9% |

| Accommodation & food services | 146,105 | 6.1% | 21,175 | 5.1% | 2,480 | 3.9% |

| Information & communication | 181,615 | 7.5% | 38,825 | 9.4% | 6,915 | 10.9% |

| Finance & insurance | 54,470 | 2.3% | 8,530 | 2.1% | 2,080 | 3.3% |

| Property | 98,920 | 4.1% | 15,305 | 3.7% | 2,580 | 4.1% |

| Professional, scientific & technical | 387,210 | 16.1% | 74,515 | 18.1% | 13,985 | 22.0% |

| Business administration | 204,925 | 8.5% | 37,090 | 9.0% | 6,340 | 10.0% |

| Public administration & defence | 7,130 | 0.3% | 1,255 | 0.3% | 85 | 0.1% |

| Education | 42,515 | 1.8% | 7,680 | 1.9% | 1,175 | 1.9% |

| Health | 92,380 | 3.8% | 15,300 | 3.7% | 2,180 | 3.4% |

| Arts, entertainment, recreation & other | 156,355 | 6.5% | 26,810 | 6.5% | 4,265 | 6.7% |

| Total | 2,408,040 | 100.0% | 412,650 | 100.0% | 63,490 | 100.0% |

Table 10. Number of VAT and/or PAYE based enterprises by broad industry group Source: ONS UK business: activity, size and location

Healthy Environment

Utilisation of Healthy Environment

Nationally cycling levels increased in 2020 to the highest levels seen since the start of the series, with increases seen in trips, stages and miles cycled. Nationally cycling as a proportion of trips by all transport modes increased from 2% in 2019 to 3% in 2020. Cycling can also boost your mood, improving the symptoms of some mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.

The Active Lives Survey (2022) for Surrey shows a decline in cycling for travel at least once a month from 10% in 2019 to 6% in 2021. For the same period South East declined from 8.7% to 6.5% and England 7.6% to 6.4%.

Noise

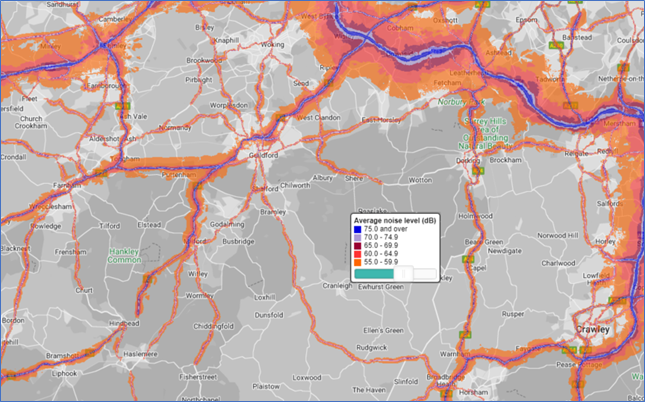

The link between noise exposure and mental health disorders is gaining increasing attention because noise pollution is an ongoing factor effecting populations in urbanised areas. A systematic review and meta-analysis looked at research published between 2000 and 2022 in order to evaluate whether the available evidence supports an adverse association between noise annoyance and mental health problems in people. It was found that noise pollution is potentially an important mediator of the relationship between noise exposure and mental health outcomes.

In Surrey 6.2% of the population were exposed to road, rail and air transport noise of 65dB or more during the daytime in 2016 which was higher when compared to those living in the South East where 4.9% of the population were exposed. Similarly, the percentage of the population exposed to road, rail and air transport noise of 55 dB or more during the night-time was higher at 12.8% in Surrey when compared to the South East region at 8.6%.

It is difficult to interpret this data and long-term trends are currently misleading due to the impact that Coronavirus has had on road, rail and air transport. For example, long-term trends for traffic volume have been skewed and traffic levels in 2021 were lower than 2011 levels. Similarly, there has been a decrease in passengers flying with a 23% fall in passengers compared to the same period in 2019. It is difficult to currently predict when road, rail and air transport may surpass pre-pandemic levels and the impact that these noise levels will have on Surrey’s population.

In 2019/20 rates of complaints regarding noise in Surrey were lower than the South East average of 4.5 complaints per 1000 at 3.7 per 1000. Although Surrey’s average was lower than the South East’s, at District & Borough levels these rates differed with Guildford and Runnymede having rates of complaints over the regional average (5.4 per 1000 and 4.9 per 1000 respectively) and Waverley having the lowest (2.1 per 1000).

Surrey noise impact areas

Figure 17: Source England Noise and Air Quality Viewer

Social Isolation and Loneliness

Social isolation in social care users in Surrey is comparable to the region and England, with over half of social care users reporting not having as much social contact as they would like.

Less than a quarter of adult carers in Surrey reported having as much social contact as they would like significantly worse than the regional and national reports on social contact.

Social Isolation Carers

| Indicator | Period | Surrey | Region | England | Worst | Best |

| adult social care users who have as much social contact as they would like 18+yrs | 2019/20 | 47.3% | 45.9% | 45.9% | 34.3% | 56.6% |

| adult social care users who have as much social contact as they would like 65+yrs | 2019/20 | 43.7% | 42.9% | 43.4% | 30.4% | 53.8% |

| adult carers who have as much social contact as they would like 18+yrs | 2018/19 | 22.4% | 31.4% | 32.5% | 11.7% | 45.7% |

| adult carers who have as much social contact as they would like 65+yrs | 2018/19 | 24.2% | 32.7% | 34.5% | 11.1% | 50.9% |

Table 11: Social Isolation Carers Source OHID Fingertips Public Health Profiles

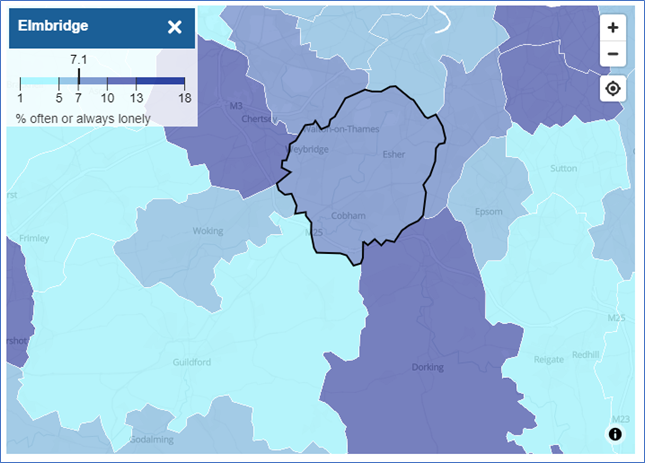

The ONS has produced a map of loneliness by local authority based upon data from the 2020/21 Opinions and Lifestyle Survey, % response to “often” or “always” feeling lonely. Highest levels of loneliness were reported in the Mole Valley (10.9%),

Loneliness rates by local authority

Figure 18. Percentage reporting “often or always” feeling lonely, Oct 2020 to Feb 2021 Source: ONS. Mapping loneliness during the coronavirus pandemic

6. Populations at Risk

Young Adults

Instances of self-harm are more common in children and young people, and as many as 25.7% of women in England between the ages of 16 to 24 report that they have self-harmed at some point in their lives.

Trends reported by Public Health England on Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing indicate the number of hospital admissions in 2020-21 as a result of self-harm in Surrey for 10-24 year olds is increasingly getting worse (468.7 per 100,000 in Surrey, 505.6 Regionally and 421.9 in England).

More information can be found in the Emotional Wellbeing and Mental Health chapter of the JSNA which covers young adults. This chapter is currently being rewritten with an expected publishing date of June 2023.

Adults

People open to an Adult Social Care Mental Health Team in Surrey as a service user, excluding unknown addresses and under 18s, by Age

| Area | 18 – 29 | 30 – 39 | 40 – 49 | 50 – 59 | 60 – 69 | 70+ | Grand Total |

| Elmbridge | 33 | 27 | 39 | 40 | 39 | 24 | 202 |

| Epsom and Ewell | 21 | 24 | 31 | 19 | 33 | 10 | 138 |

| Guildford | 49 | 47 | 50 | 62 | 47 | 15 | 270 |

| Mole Valley | 30 | 15 | 33 | 30 | 32 | 15 | 155 |

| Reigate and Banstead | 35 | 67 | 57 | 65 | 71 | 30 | 325 |

| Runnymede | 10 | 14 | 25 | 19 | 27 | 10 | 105 |

| Spelthorne | 29 | 33 | 25 | 47 | 20 | 11 | 165 |

| Surrey Heath | 26 | 22 | 23 | 41 | 18 | 8 | 138 |

| Tandridge | 13 | 16 | 13 | 20 | 20 | 6 | 88 |