JSNA Housing and Related Support

JSNA Housing and Related Support

Publication date

This chapter was published in January 2024 and is due to be reviewed by January 2026

Contents

- Introduction

- Key Facts on Housing in Surrey

- Homelessness

- Local Insights

- Needs of Specific Groups

- Issues that may impact on housing services in Surrey

- Services in Relation to Need

- Key Findings and Recommendations

- Appendices

- Data sources

- Contacts and Acknowledgements

- References

Introduction

Housing plays a fundamental part in people’s wellbeing, their employment, health, and relationships.

The Community Vision for Surrey 2030 states, “By 2030, Surrey will be a uniquely special place where everyone has a great start to life, people live healthy and fulfilling lives, are enabled to achieve their full potential and contribute to their community, and no one is left behind.” One of the underpinning principles is that “Everyone has a place they can call home, with appropriate housing for all.”

‘A Housing, Homes and Accommodation Strategy for Surrey’ recognised that Surrey is in the grip of a serious housing crisis. This housing crisis manifests most critically in the supply of homes that are truly affordable for local people, at all tenures and most income groups.

Aims and Objectives

This Needs Assessment aims to create a picture of the housing situation in Surrey and how that is affecting people’s health to inform commissioners and stakeholders. We aim to lay out the current provision of services and highlight gaps in that service provision to identify the housing needs of all those living in Surrey. This Needs Assessment recommends priority actions for immediate and long-term response.

Scope

This Needs Assessment covers all people living in Surrey with focus on priority groups identified during a scoping exercise with Stakeholders.

This needs assessment covers all types of homes and tenures in Surrey apart from Care Homes and residential homes which are covered in the Safeguarding Adults chapter.

Approach

A mixed methods approach to data collection was adopted and consisted of:

- A review of relevant guidance, policies, legislation and best practice.

- A review of publicly available data on the topic in the UK.

- A review of data submitted by key stakeholders on housing in Surrey.

- A review of local reports from stakeholders and surveys on user experience in Surrey.

- Conversations with stakeholders and surveying stakeholders to find out the important issues surrounding housing and health in Surrey.

Housing and health

The links between housing and health are well evidenced. In general, the evidence on the relationship between housing and physical aspects of health (such as the link between damp homes and respiratory conditions) is more well-established than the evidence on mental wellbeing impacts. There is growing evidence of the effects of poor housing conditions on increasing stress and feelings of disempowerment and loss of control, all of which have clear links with mental health outcomes. [1]

Housing is a wider determinant of health and as such having a stable and secure home is one of the foundations of a good life. The condition and nature of homes, including factors such as stability, space, tenure and cost, can have a big impact on people’s lives, influencing their wellbeing and health.

Further information around the key housing factors which impact on wellbeing and health are described below.

Tenure

Housing tenure is related to the differences in peoples housing circumstances and support and therefore security. A secure, comfortable home enriches our lives and supports our mental and physical health. [2]

Owner Occupiers typically report better health and wellbeing outcomes and live longer than those living in social housing. Some of this variation may be explained by confounding factors such as age and income however even when these factors are accounted for there is some true difference in health outcomes across housing tenures. [3]

Tenure is linked to housing conditions and a person’s immediate surroundings and connection to their neighbourhood which all affects a person’s wellbeing. For example, owner occupiers often have more control over the immediate environment in which they live and social landlords provide services and opportunities for tenants (for example employment support and social events). [4] On the other hand tenants in the private rented sector may be isolated and at greater risk of housing related harms. HMOs (houses in multiple occupation) often have poorer physical and management standards than other privately rented properties. Occupiers of HMOs tend to have the least control and choice over their housing circumstances.

Condition

Poor housing conditions can put a person at significant risk of health problems. The most obvious and shocking examples of this were the Grenfell Tower tragedy, alongside the death of Awaab Ishak in December 2020 in a property not fit for purpose.

If a home is in a poor state of repair or if there is a hazard or immediate threat to a person’s life, they may be a source of injury (such as falls) or fire. Homes that are not effectively insulated or heated can be damp and cold which is linked to the exacerbation of respiratory problems (such as asthma and COPD) and excess deaths due to cold. Homes that are not effectively insulated or adapted for hot weather can also impact health, leading to excess deaths from heat. As the climate continues to warm, we can expect to see more frequent and more extreme heatwaves in future, and more health impacts as a result.

One of the causes of excess winter deaths is fuel poverty (which means people can’t afford to properly heat their homes) which has been shown to be as important a driver of health for young people as it is for frail elderly people.

Poor housing conditions can increase the risk of depression, stress, and anxiety. For example, there is strong and growing evidence on the mental health and wellbeing impacts of fuel poverty and cold homes, and the significant benefits to mental wellbeing from tackling fuel poverty across the entire age-range.

Overcrowded living conditions can put strain on family relationships and reduce privacy and limit space to study/play for children, which can lead to psychological stress. Overcrowding also leads to increased risk of infectious disease transmission

It can however be difficult to separate out the impact of specific housing-related hazards from other confounding factors (such as socioeconomic status or age), which in themselves may give rise to poor health outcomes and are also linked to housing circumstances [1].

Affordability and availability

Surrey (along with the rest of the country) is in the grips of a housing crisis. Lack of affordability and availability of housing related to people’s ability to afford and access housing that suits their needs and circumstances. Difficulty paying the rent or mortgage can cause stress, affecting our mental health, while spending a high proportion of our income on housing leaves less for other essentials that influence health, such as food, and social participation. This is particularly pertinent in 2023 due to the cost-of-living crisis – this has seen houses become less affordable across all tenures. [1]

Homelessness

The health of people experiencing homelessness is significantly worse compared to the general population, and the cost of homelessness experienced by single people to the NHS and social care is considerable. Homelessness is associated with poor physical and mental health and short life expectancy.

Homeless people are more likely to die young, with an average age of death of 47 years old and even lower for homeless women at 43, compared to 77 for the general population, 74 for men and 80 for women. It is important to note that this is not life expectancy; it is the average age of death of those who die on the streets or while resident in homeless accommodation. Health needs can also be a reason a person becomes homeless in the first place.

A 2017 report commissioned by the Local Government Association found that 41 percent of homeless people reported a long-term physical health problem and 45 percent had a diagnosed mental health problem, compared with 28 percent and 25 percent, respectively, in the general population. The last conservative estimate (2010) of the healthcare cost associated with this population was £86 million per year [5].

Homeless people are more likely to have problems with substance use, which is both a cause of homelessness and a route to addiction. Homeless people who drink alcohol more heavily and abuse drugs are more likely to die from these causes.

Rough sleepers are more susceptible to health impacts due to severe weather and vulnerable to climate change impacts as severe weather becomes more common such as cold and heatwaves

Mental ill health can be a cause and a consequence of homelessness. Rough sleepers are more than 35 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population.

Experiencing violence, fatal traffic accidents, infections and falls are also all more common causes of death in the homeless population.

Homelessness has particularly adverse consequences for children and can affect life chances. Starting life in temporary accommodation may impact on access to universal health care, such as immunisations, and temporary accommodation is associated with greater rates of infection and accidents. Homeless children are more likely to experience stress and anxiety, resulting in depression and behavioural issues. There is evidence that the impact of homelessness on a child’s health and development extends beyond the period of homelessness.

Definitions of key terms used in this chapter

Key terms are defined below, all further definitions and acronyms are outlined in Appendix 1.

Homeless /Homelessness: Where a person or a household are homeless, they may be entitled to be rehoused by a local authority or by another housing provider on behalf of the Council. Housing providers are required, by law, to co-operate with Council in meeting their duties to the homeless.

Housing Health and Safety Rating (HHSRS): is a risk-based evaluation tool to help local authorities identify and protect against potential risks and hazards to health and safety from any deficiencies identified in dwellings. It was introduced under the Housing Act 2004 and applies to residential properties in England and Wales.

Fuel Poverty: A household is said to be in fuel poverty when it cannot afford to keep adequately warm at a reasonable cost, given their income.

Overcrowding: the situation in which more people are living within a single dwelling than there is space for, so that movement is restricted, privacy curbed, hygiene limited, rest and sleep difficult. This is commonly measured by the ‘bedroom standard’.

Private Registered Providers (PRPs): are formerly known as Housing Associations or Registered Social Landlords. PRPs are providers of social housing in England that are registered with Regulator of Social Housing and are not Local Authorities.

Key Facts on Housing in Surrey

Surrey’s reputation and brand is as a place of prosperity. Historically Surrey has been seen as the detached-house-with-space-for-two-cars sort of place. And whilst this is true for a significant proportion of the population, it can mean housing issues experienced by others are hidden.

This section looks at the housing situation in Surrey and the number of people affected by housing related issues that impact health.

Tenure

As we would expect Surrey has a high proportion of owner-occupied properties. As shown in Figure 1, 72% of homes in Surrey are owner occupied (this includes those owned outright and those owned with a mortgage or loan). This compares to 66% for England and 68% in the Southeast.

A large number of these homes are owned with a mortgage or loan, although this number is decreasing as the number of owned outright increases (as people pay off their mortgages). It should be noted the 2023 cost-of-living crisis has seen mortgage interest rates rise leading to mortgage costs increasing significantly.

Since 2012, there has been some growth in the Private Rented Sector which is likely at the expense of people owning their own homes/ getting a mortgage. However, by comparison as shown in Figure 2 in the dashboard, the Private Rented Sector (16%) and Social Rented Sector (11%) are smaller in Surrey than those in the South East and England.

As with wider Surrey, consistently within our Districts and Boroughs the largest proportion of homes are owner occupier, with a higher percentage owned outright than owned with a mortgage in every District and Borough. Social rented housing is also the lowest proportion for all Districts and Boroughs. All Surrey Districts and Boroughs have a higher proportion of home ownership than in the South East and England, and a smaller proportion of households in social rented housing.

The next series of graphs show us tenure in relation to demographic and economic characteristics of residents in Surrey. Figure 4 shows tenure by age of resident in Surrey. This shows that the older a Surrey resident is the more likely they are to own their home outright. Adults aged between 35 and 64 are more likely to own their home with a mortgage. Young adults aged 16 to 24 are more likely to live in private rented accommodation. Interestingly those under 15 years of age are the most likely of the age groups to live in social rented accommodation as those in this age group will more likely be living with their parents this implies families are more likely to live in social rented accommodation.

Age

Household type

Household family composition by tenure shows that those aged over 65 and living alone are most likely to own their own home outright. Lone parent families are most likely to be in social housing (Figure 5).

Figure 6 in the dashboard shows tenure compared to household type in Surrey. This shows similarly that one person households are more likely to own their home outright but those in a couple household are more likely to own with a mortgage. Lone parent households are most likely to be socially renting.

Figure 7 in the dashboard shows household economic status and tenure. This shows those who are retired are more likely to own their own home outright and those who are economically active are more likely to own their own home with a mortgage. Those who are economically inactive are more likely to be in social rented accommodation.

Figure 8 shows the amount of housing stock owned by each District and Borough in Surrey. Note some Districts and Boroughs have small numbers of their own stock, and some have almost none, this is because 6 of the 11 Districts and Boroughs stock has been transferred to Private Registered Providers (also referred to as Housing Associations.

Dwelling stock

Figure 9 in the dashboard shows the number of homes in each District and Borough in total. The graph is broken down by sector of tenure. There are however some subtle differences in tenure between our Districts and Boroughs as shown in the figure. For example, Runnymede, Guildford, and Spelthorne had the highest proportions of households in social rented homes in Surrey. Woking had the highest proportion of households in private rented housing.

The number of homes (dwelling stock) over the last 5 years has been gradually increasing in all Districts and Boroughs as shown in Figure 10 in the dashboard. This combines homes in all tenures.

Figure 11 in the dashboard shows the number of dwellings in Surrey by Sector over time. This reflects tables above with most properties being privately owned. This shows that overall, the number of dwellings in the private sector (owner occupiers and private rented) and public housing is gradually increasing. However, the proportion of homes in the sector is gradually increasing at the expense of the proportion of homes in the public sector.

Some homes are classed houses of multiple occupation (HMOs). Table 1 below shows the number of HMOs in each District and Borough. The numbers of HMOs vary in each District/Borough but are likely to be an underestimate as we know many HMOs are not licensed. Guildford and Runnymede have particularly high numbers of HMOs because they have high numbers of Student Accommodation due to proximity to university in Surrey (Royal Holloway in Runnymede and Surrey University in Guildford).

Numbers of student households have increased by an average of over 60% in 10 years, with concentrations in Runnymede and Guildford where this constitutes 3.5% to 4.5% of overall housing stock.

Well-being, by tenure

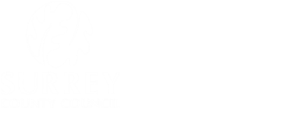

Figure 12 shows wellbeing score by tenure in England 2021-22. Self-reported personal well-being scores varied by tenure. Those surveyed were asked to rate distinct aspects of their life out of 10, owner occupiers had higher average scores for life satisfaction (7.8), thinking life is worthwhile (8.0), and happiness (7.7), and lower scores for anxiety (2.7), than the private rented sector (7.2; 7.6; 7.3 and 3.3 respectively). In turn, private renters report higher well-being scores than social renters (7.0; 7.4; 7.0 and 3.6 respectively). Among owner occupiers, outright owners showed higher scores than mortgagors for life satisfaction (7.8 compared with 7.7) and happiness (7.8 compared with 7.6), and lower scores for anxiety (2.6 compared with 2.9).

These findings may suggest that there is a direct relationship between well-being and tenure. However, there were significant differences between the types of households that typically live in each tenure, and these differences may be related to well-being. For example, social renters were more likely to be unemployed or ‘other inactive’ (this includes long-term sick or carers) than owner occupiers or private renters, as well as being more likely to be in the lowest income quintiles. This data is not available at Surrey level.

Figure 13 shows self-reported health by tenure in Surrey from the general health survey in 2021. This shows that people in the social rented sector are most likely to report themselves as in very bad health (2%) or bad health (7%). Those who own their homes with a mortgage are most likely to report themselves as exceptionally good health (66%), this is even though as shown earlier in this section those who own their own home are older. This decreases to 40% in those who own outright (this likely to be due to the fact this cohort tend to be older).

Condition

For social housing the condition of homes nationally has improved significantly since the introduction of the Decent Homes Standard in 2003. In Surrey 6 of the 11 Districts and Boroughs no longer own and manage the bulk of their own stock of social housing (this stock has been transferred to Private Registered Providers). Legislative changes mean that private rental properties could also soon be subject to the Decent Homes Standards. Additionally all domestic private rented properties must meet the Domestic Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard Regulations which make it unlawful to let a property with an EPC rating below E.

70% of dwellings in Surrey have an energy efficiency of below EPC C, indicating poor energy efficiency of Surrey’s housing stock. Furthermore, 3% of private rentals in Surrey do not meet the Domestic Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards regulations of minimum EPC E, indicating very poor energy efficiency, with increased likelihood of very high energy bills, and problems with draughts and damp. More detailed data on EPC rating of homes in Surrey can be found here: Fuel Poverty and Energy consumption | Tableau Public

The condition of social housing in Surrey can be inferred by those who meet the decent homes standard. Table 2 shows the proportion of homes by District and Borough which were deemed non-decent in the financial year 2021/22. This data includes stock owned by both Local Authorities and Private Registered Providers Figure 14 shows the number of homes by District and Borough which were deemed non-decent in the financial year 2021/22. Data is only available for four Local Authorities which manage their own stock. There are large differences in the proportion of homes meeting the decent Standard between Districts and Boroughs. For example 31% of Local Authority owned homes in Runnymede (911) didn’t meet the standard compared to 3% in Woking (85). Note that there are difference categories of HHSRS and most of these homes are deemed ‘not in a reasonable state of repair’ rather than the more serious category of ‘category 1 hazard’.

In recent months the problem of damp and mould in all housing tenures has become a more prominent issue likely linked to the cost of living crisis meaning people are cutting back on heating and insulation. Additionally nationally there is a shortage of trained, skilled repair workers who are needed to maintain, repair and refurbish affordable homes in the housing sector. This is compounded by high rates of inflation in costs and labour while rents, which provide the funding for services, have been capped, frozen or cut in recent years, reducing the income and available budget for work.

Fuel Poverty

A Housing Homes and Accommodation Strategy for Surrey highlights the impact of fuel poverty, poorly insulated homes and historic disrepair in some homes has brought a much sharper focus on how many lower-income and vulnerable residents are living in unhealthy homes.

Overall, in 2021 Surrey has smaller proportions of households in fuel poverty (7.3%) than the English average (13.1%). Waverley had the highest proportion of households in fuel poverty at 8.3% alongside Guildford with 8.1% in fuel poverty. Surrey Heath had the smallest percentage of households in fuel poverty at 5.9%.

Figure 15 show the percentages of households in fuel poverty in Districts and Boroughs in Surrey in 2021. Percentage of households in fuel poverty in 2021:

Figure 16 shows fuel poverty levels in Surrey compared to other areas in the Southeast.

Figure 17 in the dashboard shows that from 2015 to 2018 fuel poverty was gradually decreasing in Surrey, but has since then has been increasing, this reflects the national picture. It is likely fuel poverty will continue to worsen as figures are updated due to the cost of living crisis and increases in energy price across the country.

Figure 18 in the dashboard shows there is pronounced regional variation in the distribution of households experiencing fuel poverty. The West Midlands has the highest proportion of its households living in fuel poverty (around 18.5%, 2021), while the South East has the lowest proportion (around 8.4%, 2021). Southern regions tend to have average annual temperatures higher than in the Midlands and Northern England, which is one reason fuel poverty is lower in the Southern regions.

Houses in multiple occupation

Houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) often have poorer physical and management standards than other privately rented properties, sometimes involving poorly converted self-contained units without the requisite building regulations, and/or collocated with commercial premises. Added to their high occupancy, this means that HMOs are subject to greater risks of certain hazards, such as fire. Occupiers of HMOs tend to have the least control and choice over their housing circumstances, and ensuring that standards in this sector meet the legal minimum is important to protect these tenants.

The number of licensed HMOs in Surrey’s Districts and Boroughs which have been found to have category 1 hazards in the HHSRS are presented in Table 1. The numbers of category 1 hazards are small and hard to compare due to the small numbers.

Table 3 shows estimates of housing stock condition using HHSRS, this is making estimates for all dwellings regardless of tenure. The number of category 1 hazards in occupied homes in different localities has been modelled. It is estimated that Surrey has a lower proportion of homes with category 1 hazards (5.8%) than England (9.9%) and the South East (6.5%). Of Surreys Districts and Boroughs, Surrey Heath is estimated to have the lowest proportion of homes with category 1 hazards (4.3%) and Mole Valley has the highest (7.3%).

Table 4 shows estimates of homes with category 1 hazards by tenure. Surrey is estimated to have lower levels of category 1 hazards for each tenure listed than in England and the South East. As reflected nationally and regionally, it is estimated that the tenure with the highest proportion of category 1 hazards is in owner occupied properties and the lowest in social rented. This is because the condition of properties is more heavily regulated in the social and private rented sectors and people have more scope to choose the hazards they live with in the owner occupied sector.

Affordability and Availability

Surrey is in the grip of a serious housing crisis. While this is very different from the scale and severity of the housing crisis that might be seen in large cities, it is a crisis nonetheless and action is required to tackle it.

This housing crisis manifests most critically in the supply of homes that are truly affordable for local people, at all tenures and most income groups. This shortage of housing affects the lives of many local residents. It also deters or prevents people moving to, or staying in, Surrey. Critically, local businesses, the NHS and other public services are struggling to recruit and retain the staff needed to maintain good quality public services and a thriving local economy.

The strategy suggests that affordability is particularly an issue in Surrey. Due to being priced out, living in Surrey is a less feasible option for growing families, young graduates or young professionals to continue to afford to live within the county, or for workers with the skills and qualifications the economy needs, or for households to move to the county and/or businesses to locate here.

The high-quality way of life that Surrey is known for, and that residents rightly celebrate and wish to protect, is at risk from the shortage, quality and unaffordability of homes.

The nature of the crisis across Surrey is different, more complex and more challenging than in some other areas. This arises from the extremely high land values across a large geography, the very low rates of housing affordability, the very high proportion of Green Belt designations and other protected land types, an ageing population with reducing proportions of younger professionals; and the close proximity to London and Heathrow and Gatwick Airports yet failing to sustain its positive economic status compared to neighbouring regions.

Increases in student housing in places like Guildford and Runnymede in particular contributes to further pressure on private rental sector provision and housing of multiple occupation.

Key to meeting demand and tackling unaffordability is the provision of new housing to meet unmet and rising demand. Figure 19 shows the five-year average number of affordable units granted permission between April 2017 and March 2022. Some Boroughs and Districts are delivering a much greater share of this compared to others.

Occupancy rate of rooms in Surrey households

Occupancy rating provides a measure of whether a household’s accommodation is overcrowded or under-occupied. An occupancy rating of negative 1 or less implies that a household has fewer rooms than the standard requirement, positive 1 implies that they have more rooms than required, and 0 implies that they met the standard required.

Occupancy rate can also give us a demonstration of affordability and availability across the county

Figure 20 shows the occupancy rates in Surrey. Levels of under occupancy are higher in Surrey (74.8%) than in England (72.0%) and the South East (73.3%). Many older residents are living in the homes they have lived in for most of their lives, with more bedrooms than they require. There is a lack of accommodation options to attract older people to move and downsize. This is seen in the very high levels of under occupation. This is made more difficult with a lack of information about housing options and support with moving.

A lower proportion of households in Surrey lived in overcrowded homes (5.0%) is lower than the South East (5.6%) and England (6.4%). However, a total of 24,235 households in Surrey lived in an overcrowded home at the time of the 2021 Census.

Figure 21 in the dashboard shows the number of rooms in Surrey’s dwellings. Across Surrey, 52,472 households had one or two rooms (10.9%), 313,228 households had three, four or five rooms (65.0%), 100,939 households had six, seven or eight rooms (20.9%), and 15,181 households had nine or more rooms (3.2%).

In general, Surrey households had homes with more rooms than the average household living in the South East or England. In Surrey, 20.9% of households lived in homes with six, seven or eight rooms compared to 16.8% of the South East and 13.8% of England.

Homes with 9 or more rooms were also more common in Surrey (3.2%) than the South East (1.8%) and England (1.1%).

Figure 22 in the dashboard shows the number of bedrooms in Surrey dwellings. While the proportion of households in Surrey who lived in a home with just one bedroom (11.4%) was similar to the South East and England averages (11.6% each), a higher proportion of Surrey households had access to four or more bedrooms (30.9%) than those living in the South East (25.0%) and England (21.1%).

Figures 23 to 25 in the dashboard show overcrowding and under-occupancy by household characteristics: Figure 23 shows occupancy rating by tenure. Those who own their home outright are most likely to be under-occupied and those in social housing are most likely to experience overcrowding.

Figure 24 shows occupancy rating by ethnicity, and highlights that those from a Black ethnic background are most likely to experience overcrowding and those from a White ethnic background are least likely to experience overcrowding.

Occupancy rating by age or household age mix is presented in Figure 25 in the dashboard. This shows that those living in mixed age groups are most likely to experience overcrowding, implying that families potentially those with 3 generations in the same household are most likely to experience overcrowding. Those in households only with people aged 65 and over are least likely to experience overcrowding but most likely to be under occupying.

Rent prices

Table 5 shows that Rent have increased in Local Authority social housing and housing provided by a Housing Association in the last 10 years. This data lags behind new Government Policy that for rent periods that beginning in the 12 months from 01 April 2023 to 31 March 2024 social housing rents can be increased by up to 7% due to the cost of living crisis. We also know anecdotally that rents are increasing quickly and significantly in the private rented sector due lack of availability and the cost of living crisis as landlords try to make up the difference as their mortgages rise in cost.

Figure 26 in the dashboard shows that median weekly rents in the South East are some of the highest in the country after London.

Median weekly rents in the South East were second highest in the social rented sector compared to other places. Affordable rent in the South East is the third highest of any regions and intermediate rent the fourth highest of any regions (Figure 27 in the dashboard).

Within the affordable housing sector, it’s clear that, while “Affordable Rent” offers a more affordable home for some residents, it remains inaccessible to higher-need families (in particular larger, non-working household) who are unable to afford that level of rent. This leads to some high-need families remaining in Temporary Accommodation, which is insecure for residents and expensive for Local Authorities.

The number of new social lettings (number of social lettings properties that became available for rent over the year) by provider type across Surrey’s Districts and Boroughs for the 2021/2022 financial year is presented in Figure 28 in the dashboard. These new social lettings could be due to properties becoming available to let as tenants move on or new homes being built.

The numbers of new social lettings overall in Surrey and by all social lettings type had been decreasing from 2018/19 up until 2020/21 when they began to increase (Figure 29 in the dashboard). Similar trends have been seen nationally and it is likely It is likely that the sudden increase was due to a rebound effect from 2020/21 where COVID-19 restrictions caused a large decrease in new social lettings.

In all of Surrey’s Districts and Boroughs the rate of new social lettings per 1,000 population is lower than in England (4.48 per 1,000) and the South East (3.64 per 1,000) (Table 6).

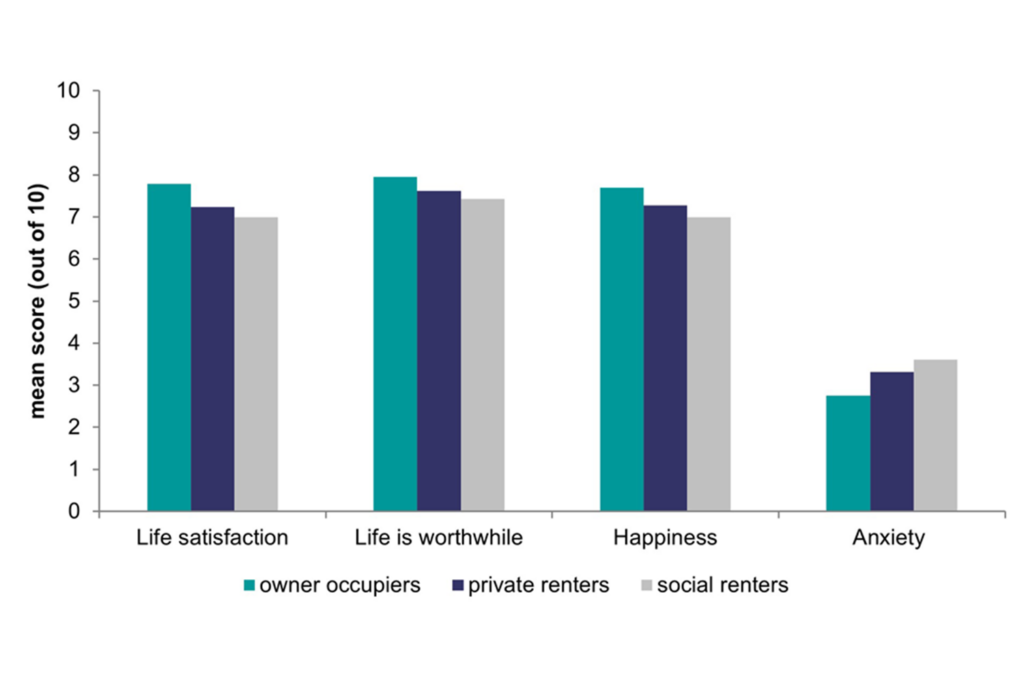

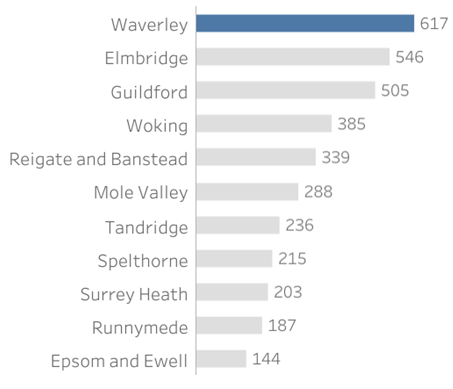

The number of long term empty homes varies across the Districts and Boroughs. With more than 1,400 in Guildford and less than 400 in Tandridge (Figure 30). The Surrey Housing Strategy suggests while there is mileage in looking at empty homes to help with the housing crisis it will not make much difference with meeting the shortfall.

Figure 30

Source: DLUHC, Local Authority Council Tax Base, 2021

Homelessness

Both statutory homelessness and rough-sleeping are growing problems nationally and across Surrey. The numbers of household approaching their local authority for assistance with homelessness varies considerably across Surrey as shown in Figure 31 (although it should be noted that these are numbers and not rates so does not reflect how many people live in each local authority).

Surrey has a lower rate of households assessed as homeless (2.74 per 1,000) compared to England (6.08 per 1,000) and the South East (4.71 per 1,000) (Table 7). The rate of households assessed as homeless in Surrey Districts and Boroughs varies but is generally lower than England and the South East with the exception of Epsom and Ewell (4.80 per 1000). The rate of households assessed as threatened with homelessness is also lower in Surrey (4.05 per 1,000) compared to England (5.63 per 1,000) and the South East (4.81 per 1,000). However, some of Surreys Districts and Boroughs have rates higher than England (Woking at 6.29 per 1,000 and Spelthorne at 5.95 per 1,000). Rates vary across the Districts and Boroughs with the lowest rate being in Surrey Heath (1.49 per 1,000) (Table 7).

Figure 32 shows the number of statutorily homeless households placed in temporary accommodation by the local authority (quarterly data January to March 2023). Numbers vary across the county but are highest in Epsom and Ewell and Reigate and Banstead.

The expectation would traditionally be that in larger conurbations people are more likely to become homeless than in smaller settlements. “Urban areas also have the highest rate of homelessness, with approximately 29 homeless people per 10,000. By contrast, rural areas have a rate of less than half that, with 14 people experiencing homelessness per 10,000.” (Are there more homeless people in cities or rural areas?)

Also, homeless numbers would be anticipated to be lower in more affluent areas than in those that are more deprived. Deprivation exists in all Districts and Boroughs across Surrey although more concentrated pockets exist in 21 wards, (known as Surrey Key Neighbourhoods)

While numbers of homeless people vary across Districts & Boroughs, there are several thousand individuals and families waiting on housing registers across Surrey, while only a few hundred are being housed in temporary accommodation. A shortage of suitable housing means that in some cases families from Surrey who become homeless are not able to remain in their local area and are placed in other temporary accommodation elsewhere in Surrey or out of the county, away from existing schools, work and social networks.

Differing homeless numbers across Surrey

The patterns of homelessness across Surrey vary considerably. All authority areas experience factors which are impacting on homeless numbers such as:

- Lack of affordable privately rented accommodation

- A disparity between welfare benefit housing payments and private rents

- Limited numbers of social housing properties

- Rising mortgage payments

- Parental evictions

- Relationship breakdown

- Households with multiple social and health issues such as drug and alcohol abuse, mental health illnesses etc.

- Changes in those being displaced from other countries. For example many of those welcomes from Ukraine are now being asked to leave by their hosts resulting in homelessness

The above issues are likely to be more impactful in deprived areas as resident’s financial resilience is likely to be lower than in more affluent areas.

Access to social housing is inconsistent across the County as the number of units per head of population differ markedly. Furthermore, homelessness rates differ and authorities who no longer have their own accommodation have less control over access than they did historically (see Figures 28 and 33 which show that high levers of social letting by private registered providers in Surreys Districts and Boroughs). Additionally, levels of privately rented accommodation within each District and Borough vary considerably presenting different challenges to each authority to gain access to the accommodation required.

Differences in the levels of homeless can be because authorities often interpret the homeless legislation differently leading to disparities in assistance for households.

Households more vulnerable to homelessness

Headline homelessness data can hide some inconsistencies in the propensity of households to become homeless.

Individuals with protected characteristics are much more likely to become homeless compared to the population as a whole. For example, those with a disability and from a minority ethnic background. [6]

Ethnic group

The majority of lead applicants of homeless households are White in Surrey, representing 72% of households owed a duty. White individuals comprise 84% of the population in England, suggesting they are underrepresented in the homelessness population.

Lead applicants of Black, Mixed and Other ethnicities are over-represented in homeless households owed a duty, representing 13% of households compared to the combined 7.5% they comprise of the population in England.

Black lead applicants are the most disproportionally homeless.

The ethnicity of main applicants assessed as homeless in Surrey by ethnicity is presented in Figure 34 in the dashboard.

Age

In Surrey 28% of main applicants were aged 25 to 34 years old and 23% are aged 35 to 44. This masks the number of children who are considered homeless as they will not be the main applicant. The ages of main applicants assessed as homeless in Surrey are shown in Figure 35.

Employment status

Nationally 35.7% of main applicants were registered unemployed at the time of application.

Those experiencing domestic abuse

Nationally 30.7% of households with children were owed a relief duty due to domestic abuse.

LGBTQ+

The recorded sexuality of main applicants who are homeless in Surrey shows that 3% of applicants describe themselves as homosexual or other. However, nearly a third of applicants chose not to describe their sexuality meaning it is likely higher (Figure 36).

A higher proportion of households in Surrey (53.0%) owed a homelessness duty have a support need than in England (51.7%) and the South East (52.1%) (Figure 37 in the dashboard). This remains true when those households where the support need is unknown is taken into account.

The same data in Figure 37 is broken down further in Figure 38 in the dashboard to show the wide variation in those households with a support need by District and Borough compared to England and the South East.

Figure 39 shows the main reasons for support needs of those owed a homelessness duty in Surrey. Mental Health tops this list (19%) followed by physical health and disability. It is worth noting that some people will have multiple support needs which is not reflected here.

Former armed forces personnel are also more likely to become homeless and sleep rough than the population as a whole. Although additional safeguards are in place for this cohort these are failing to stop this higher propensity of rough sleeping.

People leaving institutions settings such as prison, care settings, hospitals etc. are also more likely to experience homelessness. In many cases due to their often-challenging support needs this can lead to a revolving door of regular spells of homelessness and rough sleeping.

These individuals are also often known to statutory and non-statutory agencies such as police, health, social services and housing authorities. Often their needs do not meet the thresholds to assess care or hospital settings, leaving them to present challenges to other statutory agencies, including Local Housing Authorities. There is more information on these cohorts of people in the needs of specific groups section.

What is the future looking like?

Tightening of economic conditions and increasingly restricted access to accommodation is and will continue to drive up homeless numbers. Frozen welfare benefit levels (Local Housing Allowance) are also serving to limit access to much of the private rented sector for households in receipt of benefit.

The delivery of low number of new affordable housing is also serving to drive up Housing Register numbers and impact authority’s ability to meet ‘housing need’ in their area.

Home Office Local Authority Housing Statistics tell us that in Surrey in 2021 465 new build affordable homes were built in Surrey and 23 non new build. Table 8 shows us this information broken down by provider.

Figure 40 in the dashboard shows us new affordable housing supply in Surrey by Local Authority in 2021 / 2022.

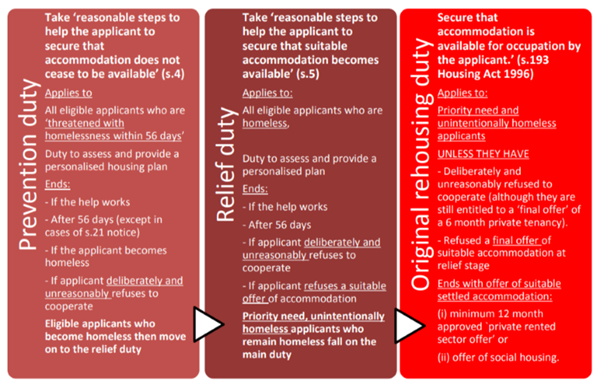

The number of households initially assessed as owed a homeless duty by financial year in Surrey is presented in Figure 41 in the dashboard. Data prior to 2018 is not directly comparable due to significant changes in the homelessness legislation, which introduced new homelessness duties through the implementation of the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 (HRA). Additionally, it is hard to consider trends in this data due to the extraordinary dip in 2020/21 due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, nationally statistics already show homeless numbers rising [7]. This trend is replicated during the financial crisis in 2008 and in recessions in the 1990s and so given the cost-of-living crisis it is predicted that homeless numbers will continue to rise until economic conditions improve. In Surrey, homelessness figures are also increasing.

Organisations who work with homeless people in Surrey, such as Rentstart have also reported an observed increase in the number of people requiring help since the beginning of the cost-of-living crisis. In the quarters following the onset of the crisis in 2022, Rentstart helped more than double the number of people than the same quarters the preceding year. Local people who have always considered themselves safe from homelessness or deprivation are now facing these situations.

The aftermath of the pandemic has also led to additional and increased issues with supporting housed clients to remain safely housed. Clients experienced increased anxiety, faced additional debt issues and often struggled to access benefits in a timely fashion.

Case Study

Rentstart work in Elmbridge and work to support homeless people into sustained tenancies. In 2021/22 they housed 127 people and made 565 interventions to prevent potential homelessness. Once housed they offer wrap-around support in financial management, employment, wellbeing and tenancy sustainment.

Rentstart worked with Tom (name changed) who spent several months sleeping in local woods after being made homeless due to a relationship breakdown. While attempting to find a way to shelter, he found a shed to sleep in at the back of some local shops. The shop owner became aware of this and allowed him to stay in exchange for him volunteering at the shop, a precarious and vulnerable situation for him. Tom did not meet the threshold to be provided with temporary accommodation arranged by the local authority,so he accessed Rentstart daily hub which provided access to showers, meals, advice and support.

Rentstart housed Tom in shared accommodation in the private rented sector in one of our managed properties. Due to the nature of the sector, he was required to manage his rent payments more strictly than if he had social housing. This began well initially, and he continued his proactive engagement, beginning life coaching, employment sessions and volunteering. However, very sadly, he became a victim of cuckooing in his new home which led to him spiralling downwards, with old and unaddressed issues resurfacing, and failing to pay his rent due to losing all of his money through the abusive relationship and at risk of being homeless again. Rentstart were once again able to provide support. They supported Tom to access services to begin rebuilding his life again in a trauma-informed and person-centred way. Tom is now proactively engaging with the right places that will get him help and allow him to independently take care of himself while he addresses ingrained and historic issues. Tom is currently sustaining a successful tenancy.

Rough Sleeping

The rough sleeping snapshot in Surrey (Autumn 2022) is presented in Figure 42. This data is captured annually on a single night and not always considered representative of numbers of rough sleepers in a Local Authority. However, we can see that the number of rough sleepers varies across Surrey with high numbers in the west of the County.

The number of people sleeping rough on the streets or in the countryside of Surrey is high by historical comparisons. Numbers have dropped considerably since a high point in 2015 and hit a relative low point during the COVID-19 pandemic, although the numbers remained higher than historic trends.

The ‘Everyone In’ initiative during the COVID-19 pandemic served to ensure that the majority of rough sleepers were accommodated. This was designed to limit rough sleeper’s exposure to the virus and improve their overall health. [8]

It is difficult to predict where trends in rough sleeping are going. It is anticipated that as a subset of homelessness, where overall numbers are predicted to rise, rough sleeping will also do the same in the short term.

Figure 43 in the dashboard shows trends in the rough sleeping snapshot data for Surrey. As described above numbers were increasing before falling in 2020 due to the pandemic and in 2022 began to increase again.

The demographics of people sleeping rough in Surrey (Autumn 2022 snapshot) shows men are far more likely to rough sleep. Six percent of rough sleepers are aged 18 to 25 and 80% of rough sleepers are UK nationals (Figure 44 in the dashboard).

Local Insights

Overview of responsibilities in Surrey

The Strategic Housing Function is carried out in Surrey by the 11 District and Borough councils who work in partnership with a range of statutory and voluntary organisations and residents to deliver the wide range of functions that sit within this role.

Broadly, the strategic housing role includes the following functions:

- Assessing and planning for the current and future housing needs of the local population across all tenures

- Housing advice and options service

- Having a Housing Allocations Policy and Housing register

- Allocations and lettings

- HMO licensing

- Disabled Facilities Grants (DFGs)

- Grants and loans assistance for housing adaptations

- Homelessness prevention, assistance and tackling rough sleeping

- Housing standards and conditions including in the private sector

- The enabling role to deliver affordable housing

From this list it is clear that there are many links between health and housing including, for example, the demand for health services being disproportionately required by those living in poor housing conditions or with the risk of falls and accidents; homeless households and rough sleepers or those living in inadequate housing or being overcrowded.

The British Research Establishment estimate the impact of poor housing on the cost of health services to be £1.4 billion per annum; similar to the health costs of smoking.

In contrast, those who are well housed, with appropriate levels of support, use health services far less.

Therefore, if health, housing, planning, social welfare agencies, landlords and residents work together to reduce housing risks, and improve housing, then there are likely to be very tangible benefits for health and housing services, as well as for the individuals and households affected.

The 11 District and Borough councils that hold the strategic housing function in Surrey are:

- Elmbridge

- Epsom and Ewell

- Guildford

- Mole Valley

- Reigate and Banstead

- Runnymede

- Spelthorne

- Surrey Heath

- Tandridge

- Waverley

- Woking

Specific responsibilities for Gypsy Roma Traveller (GRT) plots are outlined in the Needs of Specific Groups section.

Highlights from Districts and Boroughs

In delivering their housing services the district and borough councils contribute positively and significantly to the health and wellbeing of their residents. It is acknowledged that there is always more to do in terms of delivering affordable housing, helping those in housing need, improving housing conditions and providing support to vulnerable residents. These challenges are set out in other parts of this chapter including for example the fact that across the 11 District and Borough councils in Surrey 3,361 households were assessed as homeless or threatened with homelessness in the year 2021/22. However, there are also significant success stories, ambitious plans and examples of good practice that clearly demonstrate the fundamental link between housing and health and wellbeing.

Key highlights recorded below, for more in depth summaries please see Appendix 2.

Spelthorne Borough Council:

- have recently completed two high quality housing developments within the borough which provides much needed emergency accommodation for residents who are facing homelessness. These are the White House and Harper House in Ashford

- is the lead authority for the set-up and management of a step-down project across North West Surrey to deliver an integrated ‘wrap-around’ intermediate care package to support timely discharge of older residents from acute settings.

- set up Knowle Green Estates (the Council’s privately owned housing company) to deliver affordable homes and increase move-on options available to residents in emergency accommodation. Since 2018, 82 affordable rented homes have been delivered; this includes the conversion of part of the council’s offices into 25 affordable homes of which Spelthorne is the first local authority in the country to do this.

Epsom and Ewell Borough Council:

- successfully operates a Private Sector Lease (PSL), where local landlords lease their property to the council for between 3 to 5 years for use as temporary accommodation thus increasing numbers of households placed within the borough and keeping temporary accommodation costs down.

- has employed a specialist single person housing officer to work alongside East Surrey Outreach Service (ESOS), to work with the borough’s most entrenched rough sleepers. This also includes sourcing funding to set up two ‘Housing First’ units in partnership with Transform Housing & Support.

- works closely with the Housing Benefit Team and social housing providers to identify and support households affected by the spare room subsidy, to downsize a number of households, which has resulted in 8 3-bedroom properties becoming available.

Reigate and Banstead Borough Council:

- commit in their ‘Five Year Plan’ to securing the delivery of homes that can be afforded by local people and which provide a wider choice of tenure, type and size and make it clear in their Housing Delivery Strategy 2020-2025 that to achieve this they will work in partnership with housing associations, Surrey County Council, developers and Homes England

- since 2020 has directly delivered 61 new build homes, 32 secure tenancies, 4 housing first style units for homeless applicants with complex needs, 11 shared ownership homes and 14 market sale homes.

- are further increasing their local temporary accommodation stock through purchasing over 15 family homes and a shared house for single homeless applicants.

- jointly funds ESOS operated by Thames Reach. ESOS proactively work with rough sleepers and the LA to secure positive housing and health outcomes for service users.

- are also part way through an 18-month pilot with East Surrey Place part of NHS Heartlands, to deliver a Hospital Discharge Service concentrating on improving discharge times for patients that have housing issues on discharge.

Waverley Borough Council

- has committed to building homes to buy or rent for households from all income levels by harnessing the power of partnerships; aligning new supply more closely with need; ensuring synergy between services and creating homes for all out lives

- In the next 3 years plan to

- ensure that the mix of affordable homes delivered includes rented homes which would be attractive to downsizers, to free up larger affordable homes

- Enable at least one scheme per annum with wheelchair accessible homes (M43 standard) to meet the needs of older people or those with physical disabilities

- Work closely with developers and Affordable Housing Providers at planning application and pre-application stage to ensure the location, size, type, tenure and design of new affordable homes meets need

- plan strategically for the development of a range of housing options for older people, including Extra Care housing and dementia specialist care, working in partnership with Surrey County Council ASC Commissioning Team

Tandridge District Council

- work with ESOS to work with those who are sofa surfing or are rough sleeping.

- has identified that adaptations for disabled children can make the difference between a parent being able to care for their child at home or not and manage family life. As such adaptations for children up to £30,000 are not means tested.

- Have identified accommodation for older people as a specific need in Tandridge. As Surrey County Council transitions away from traditional residential and nursing care provision in the coming years, the need for extra care housing in the district is identified as critical as there are no affordable extra care units in the Tandridge District to either rent or buy, with all current provision being in the private sector which is not financially accessible to everyone.

- works with Social Services to identify at an early-stage vulnerable young people who are leaving care and who need their own accommodation by ensuring qualifying young people are registered on the Housing Register so they can be nominated to a supported housing vacancy before a crisis situation such as street homelessness occurs

- offers a Sanctuary Scheme to residents living in council property and in the private sector which enables victims of domestic abuse to remain in their own homes by providing security improvements such as the installation of spy holes in doors, improved door and window locks and security lighting. Housing Associations also offer this scheme to their tenants.

Woking Borough Council

- has delivered two new self-contained, modern temporary accommodation schemes (providing 47 units), as well as renovating its existing temporary accommodation schemes.

- has also set up a selective licensing scheme in the Canalside ward to raise the standard of private rented accommodation. 865 licences have been issued under the scheme, with 52% of properties visited being improved following inspection

- has a target to meet the need for 22 new gypsy and traveller pitches already identified in the Gypsy and Traveller Assessment up to 2027.

- has developed Brockhill and Old Woking extra care schemes. The Brockhill Scheme provides 49 homes and is located in Goldsworth Park. Old Woking scheme is a Hale End Court and provides 48 apartments, 12 of which are for tenants needing care. These are designed to meet the needs of frail or vulnerable people living in Woking and provide 24/7 personal care to help those with additional support needs to remain as independent as possible.

- offers a range of support services designed to promote ongoing independence and wellbeing. The council’s independent support service works in partnership with other external agencies to offer support to anyone who needs it, regardless of tenure.

Mole Valley District Council:

- have identified the needs of older people as a specific area of concern and plan to enable and facilitate the development of extra care schemes for older people located close to facilities in the towns of Leatherhead and or Dorking.

Guildford Borough Council:

- have developed a number of additional supported living projects for people with learning disabilities over the past ten years, and are planning to build 12 flats next to Guildford Fire Station. The county council having nomination rights to four of these units, which will be used to house people with learning disabilities who are able to live independently but who require some level of support.

- provide two Extra Care housing schemes in the borough: Dray Court and Japonica Court. These cater for older people with higher support needs than those in sheltered housing, allowing them to receive the care they need whilst retaining their independence. An on-site social care team can provide care and welfare support for up to 24 hours a day where necessary.

- recognises that many older people, are still in housing need and under occupy large family homes and offers support and help to older tenants who are willing to downsize and will continue to consider ways in which they can offer more attractive housing options for their older residents including on new developments.

- aims to provide some new Traveller accommodation directly having received planning approval for five Traveller pitches at Ash Bridge and were successful in gaining a grant allocation of £432,000 from the Homes and Communities Agency.

Surrey Heath Borough Council:

- Delivered Surrey County Council’s Floating Housing Support Service which allowed the Council to successfully bid for an additional Support Officer within the service specifically working on homelessness prevention and resettlement with single people.

- To support the timely delivery of Disabled Facilities Grants and other adaptations Surrey Heath has secured Better Care Fund money to employ a Housing OT within the Housing Service. This will speed up assessment for DFGs as well as support housing needs work around housing allocations and homelessness where an applicant has a disability.

- have initiated a number of projects to address the needs of single homeless residents and rough sleepers. Following a successful project that led to the setting up of a local charity, the Hope Hub, providing crisis and day services, two accommodation projects have been delivered using developer contributions.

- the purchase of a 10 bed former temporary accommodation scheme from a housing association. This is now run by the Council as a supported housing scheme for single homeless individuals.

- the purchase of a 6 bedroom street property now leased to the Hope Hub to provide an Emergency Accommodation Scheme for single people, allowing a period of assessment and support to explore housing options.

Runnymede Borough Council:

- Is part of the successful StepDown scheme, using a number of Council properties to free up hospital beds when a patient is medically ready to leave hospital.

- Have dedicated engagement and inclusion staff offering a range of methods to enable us to listen to the views of customers previously under-represented and lead diversity awareness and community engagement events.

- Built nine new Council apartments in Addlestone in 2022, launching a commitment to deliver 125 new council homes in 5 years.

- Significantly increased investment in council owned homes included solar panels and energy efficiency measures.

- Support With Moving Policy offers practical support and financial incentives for tenants giving up larger, family sized properties who are willing to downsize to a smaller home.

Locations within Surrey

Housing deprivation is not evenly distributed within Surrey – See Fig. Below

Surrey’s Health and Well-being Strategy was refreshed in 2022 to include a particular focus on certain geographic areas of the county which experience the poorest health outcomes in Surrey. These areas were selected on the basis of the overall deprivation score established in the English deprivation indices 2019.

The “Key Neighbourhoods” for especial prioritisation are the wards which included the most deprived “pockets” within the county. These small areas are called Lower Super Output Areas (LSOA)s:

Table 9 shows these ‘Key Neighbourhoods’ and the decile they sit in for the Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) overall and also for the barrier to housing decile. The deciles are calculated by ranking the 32,844 LSOAs in England from most deprived to least deprived and dividing them into 10 equal groups. LSOAs in decile 1 fall within the most deprived 10% of LSOAs nationally and LSOAs in decile 10 fall within the least deprived 10% of LSOAs nationally. Most are in the Lower 5 deciles for barriers to Housing.

Note: The Wider Barriers Sub-domain measures the financial accessibility of housing such as affordability; it is part of the Barriers to Housing and Services Domain of deprivation (Source: Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities English Indices of Deprivation 2019).

Figure 45 shows a map of Barriers to Housing Domain of deprivation (wider barriers sub-domain) at LSOA level in Surrey, which includes issues relating to access to housing such as affordability:

This shows that there is much geographical variation throughout Surrey for this indicator, but the North of the county is more likely to be more deprived when it comes to the wider barriers affecting housing.

Rural Housing

There are particular issues for those living in rural areas in Surrey. Around 50% of the land area in Surrey is rural, but it hosts less than 12% of residents.

Rural areas in Surrey have an older age profile than elsewhere, with almost a quarter of its population being over 65 years. In fact, the over 65 years age group is the only one that is growing in rural Surrey, with all younger age groups seeing a decline in recent years. Factors such as high housing prices and overall cost of living will inevitably lead to an increasing age and affluence profile of rural Surrey. Many of the older population live in large older properties and finding accommodation to downsize locally is a challenge. More traditional, smaller properties have often been extended.

Affordability and a lack of affordable and social housing is seen by many as a key issue for rural Surrey. Large areas of the county fall within the Green Belt, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and Areas of Special Scientific Interest, many settlement areas are subject to conservation area regulations and land prices are high which drives up the cost of housing in rural areas.

Being within easy reach of London makes many of the villages an ideal choice for commuters; house prices are cheaper than London, whilst salaries in London are higher, this means local people on a median salary are finding it increasingly difficult to afford the current housing market. This together with the loss of council homes under Right to Buy, and the increased cost of private renting leaves some people with little choice but to move away, continue living at home with relatives or remain in the expensive and insecure private rented market. This impacts people feeling secure in their homes and feeling part of the wider community.

For village life to be sustainable there needs to be a mixture of age groups, incomes and household types to maintain services such as schools, local pubs, the post office and bus links. Lack of affordable housing results in rural communities having an unbalanced social and economic mix with mainly older or wealthy householders.

Creating affordable housing also has an economic benefit with the economy being boosted by £1.4 million and generating £250,000 in government revenue for every ten houses built.

There is a Rural Exception Policy, that is specific to rural areas that can be used to help. The National Planning Policy Framework refers to rural exception sites as “Small sites used for affordable housing in perpetuity, where sites would not normally be used for housing.” Rural exception sites seek to address the needs of the community by accommodating households who are either residents or have an existing family or employment connection. A proportion of market homes may be allowed on the site at the local planning authority’s discretion, for example where essential to enable the delivery of affordable units without grant funding or to enable a lower rate of rent to be charged.

Insight from the community

In order to add meaning to the findings outlined so far in this chapter through data and statistics it is important to reflect conversations, consultations and stories from the local community who live in Surrey, those who work in housing in Surrey and others with a vested interest. This is partly done through the case studies scattered through this document and found in more detail in Appendices 3-6. In addition below we have collated insight from relevant existing pieces of work and also conversations had in developing this chapter which can help us to develop our health and wellbeing recommendations in relation to housing.

Concerns of District and Boroughs

Whilst developing this chapter we asked Surreys Housing Enabling Officers what they thought the biggest issues for housing in Surrey are.

‘Truly’ affordable housing came out as the top concern with officers highlighting that the governments definition of ‘Affordable Housing’ includes housing that isn’t actually affordable. Lack of affordable housing is also tied in with supply and planning constraints meaning a lack of available land for development.

Officers also mentioned:

- Affordability of the private rented sector

- Lack of temporary accommodation (particularly for those with complex needs and large households)

- Lack of joined up policy

- Cost of living crisis

- Lack of social housing

- Lack of political will / political priorities

- Financial positions of councils impacting ability to deliver

- Lack of supported housing for people with complex needs

- Supporting refugees into appropriate housing

Consultation on A Housing, Homes & Accommodation Strategy for Surrey

Following the development of A Housing Homes & Accommodation Strategy for Surrey, Surrey County Council undertook a consultation. The consultation was open to the general public, and received 106 responses. The consultation aimed to gain insight from the local community as to which topics identified in the strategy they felt were most important. Of the respondents 101 lived in Surrey and 49 work in Surrey. Five people own a business in Surrey. Most respondents (68) own their home outright or with the help of a mortgage. Most respondents were employed full-time.

Responders were asked to say how important they felt the topics identified in the Strategy are. Figure 46 below shows the percentage of respondents who felt each topic was very important. Although this consultation was specific to the outcomes of the strategy it gives us some idea of what the community in Surrey thinks is important when it comes to housing.

Housing unaffordability had the largest percentage of people feeling it is very important (77.4%) followed by understanding public opinion. An aging population is the topic least respondents felt was very important (37.7%) and most respondents felt was not important at all (18.9%).

An explanation of each topic is below:

Partnership working – This refers to the need for greater partnership working in Surrey in relation to the provision of housing and accommodation.

Understanding Public Opinion – This refers to concerns about public opinion regarding growth and development as a barrier to partners confidently committing to long-term joint working on housing growth.

An Ageing Population & Under Occupation – This refers to the issue of under-occupation (e.g. a house having more bedrooms than there are occupants) worsening housing supply problems and reducing availability for families.

Housing [Un]affordability – This refers to higher house prices making it a less feasible option for growing families, graduates, essential workers or young professionals to afford to live in the county.

Supporting Vulnerable Residents – This refers to multiple agencies and organisations working together to maximise what they have for the benefit of residents who need that support (e.g. high-needs families, migrants or individuals).

Public Sector Land (Collective action and taking greater control over quality, quantity & price of homes) – This refers to identifying available public sector owned land for housing development and the need to pool resources and share the benefits to allow partners greater control over the type, scale, size and affordability of housing in their local area

More Councils, enabling more housing delivery – This refers to the opportunity for councils to prioritise housing delivery, addressing the challenges of funding, planning constraints, capacity, and working in partnership.

The Climate Crisis – This refers to changing investment priorities away from new housing development and into retrofit and refurbishment of existing homes due to concerns over climate-based resistance to new housing.

Feedback to HealthWatch

HealthWatch have collated case studies on the condition of homes, impact on health and ability to get help which are reported below:

Case study 1 May 2023

I’ve had problems with my housing that why I’m [at the warm hub]. There’s a problem with the humidity and the place is just damp. I have a track record going back several years with the housing team at the council, which doesn’t help. It’s a battle trying to get someone to come out. I did talk get help in the end – an organisation helped me write to the council and someone did come out in the end.

Case study 2 February 2023

Been living in UK since 2001. Rent house through a Private Registered Provider. There is mould in the kids’ bedrooms and in my bedroom. It is cold but I am having to leave the windows open to get some air in the room. My 5 year old has a cough and struggles with his breathing. I have a cough too. I have complained to PA Housing but nothing. I have to change the sheets a lot as they are damp and mouldy. It’s horrible. The children are squeezed into a room and are sleeping on mattresses on the floor pushed up right against the walls. It’s not nice for them.

It’s hard to get an appointment with the GP. I have 6 kids. When I try to get an appointment, I feel like I am fobbed off. I am worried. I want to change GP; I heard there is one in Hersham that is good but that there is a long waiting list. [another lady recommended Ashley Medical Centre to her]

I have arthritis and it’s getting more and more painful. [advised to contact GP again]

I took my 12 year old to St Peters [2022], there was a long wait in A&E but the service was good. It was a good experience overall.

I’m very stressed about the cost of living. It’s very hard when you have six children.

Case Study 3:

HealthWatch found that Ukrainian refugees main concern was housing. One refugee told their story:

I have been in Caterham since March last year. Living with Aunt initially and then we moved to a hotel and now a hostel with my sister and our children. We had to leave our partners behind in Ukraine. We have rooms opposite each other. Previously we had to share a bed which wasn’t ideal.

**What could make your life better** – right now, we don’t care about health, it’s all about living arrangements. We want to be settled in our own house and working and contributing to family life.

Other insights

Surrey County Council and Surrey Heartlands have carried out research to gather a deep and broad understanding of what is happening on the ground for residents, exploring resilience and support and identifying opportunities in the context of the cost of living crisis. The findings below are from research in the 5 most deprived wards in Surrey with a focus on those who are seldom heard but have been most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost of living crisis. Research was done through community walkabouts, stakeholder engagement interviews, an online survey and ethnographic research (16 households). The findings related to housing are outlined below.

86% of residents have said they are cutting down on household bills. One woman in Court Ward said ‘Bills just keep coming which we both cannot pay. Council tax and heating are big ones. We work part time to be around for our kids, so if we paid all our bills back in full we would have no money to feed them or ourselves. My friend sends her kids to me when her fridge is empty and I do the same to her’,

The report highlighted the link between cost of living and poor health with examples such as

‘For me the cost of living crisis has just added and multiplied what I’ve already been going through. I have a chronic condition which stops me from working, and I’ve had to battle with housing to get back on the register since my ex left me in debt in the current housing association flat we are in. It feels like all the services are a bit inaccessible right now’

The report makes the recommendation that councils should not be pushing people further into debt and should find ways to consolidate debt and help with breaks in payment including working with housing and landlords to freeze council tax and rent.

Needs of Specific Groups

Age

Evidence shows that those who are youngest and oldest in our society are more at risk of housing-related health problems. For example, older people are more at risk of fuel poverty. Those aged over 75 are most likely to be living in homes that are too cold or lack modern facilities. Older people are also at greater risk of falls from housing related issues with many homes requiring adaptations. They are also more likely to live alone and be at risk of social isolation [9]. Children on the other hand are more likely to live in overcrowded housing which can impact social, mental and physical development. [10]

Nationally, young people are one of the worst groups being hit by the cost of living crisis and its impact on housing as mortgage rates increase making it harder to own your own home and landlords pass on the increase to renters. Affordability is a growing national issue and the situation is particularly pronounced for young graduates and professionals..

As shown in the key facts section, the younger someone is the more likely they are to be in social or private rented housing. The older someone is the more likely they are to own their home with a mortgage and those aged over 65 are most likely to own their own home outright.

For those known to adult social care, a person with a learning disability is less likely to be living independently the older they are. For those with mental health issues the 2023 general trend is for older age groups to be more likely to live independently, up to the age group of 45 to 54 and after that the percentages decline.

People experiencing domestic abuse

Experiencing domestic abuse is associated with a number of health risks including depression, anxiety, PTSD and substance. People experiencing domestic abuse are also more likely to experience homelessness compared to the general population. Domestic abuse can lead to insecure housing and the issues described earlier in this chapter associated with that. There may also be health risks for children and others within the family, who witness abusive incidents.

Concerns on current or future housing options can make it difficult for those experiencing domestic abuse to leave their partners. The Domestic Abuse Report 2020: The Hidden Housing crisis, found that survivors are sometimes weighing up staying in a home shared with an abuser or leaving for another potentially unsafe situation due to lack of housing. There are also fewer housing options for those survivors who are not eligible for public funds (due to immigration status) as they are not entitled to housing related benefits or for housing help from any local authority.

Establishing a clear picture of the extent of domestic abuse in Surrey is difficult as it is often a hidden crime and under-reported. However it is estimated in the UK 1 in 5 adults will experience domestic abuse.

Surrey Domestic Abuse Partnership (SDAP) is a group of independent charities who work together across the whole of Surrey to ensure that survivors of domestic abuse are safe, and to build a future where domestic abuse is not tolerated. The service is open to anyone affected by domestic abuse regardless of age, gender, sexuality, religion, mental and physical health.