JSNA Substance Misuse

Substance Misuse Joint Strategic Needs Assessment

Publication date

This chapter was published in April 2024 and is due to be reviewed by April 2026.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Recommendations

- Introduction

- Scope and methods

- Terminology

- National and local strategic context

- National drug and alcohol use patterns

- Drug and alcohol use in Surrey and its impact

- Drug and Alcohol related hospital admissions and deaths in Surrey

- Drug and alcohol related crime

- Evidence base for interventions

- Prevention, treatment and recovery services in Surrey

- Engagement with treatment

- Stakeholder insights

- Feedback from service users and others affected by drug related harm

- Work taking place to improve the system in Surrey

- Recommendations and rationale for inclusion

- Lead contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

Executive Summary

Context

Misuse of drugs and alcohol is a major public health concern with wide-ranging effects on our society including the health, care and financial consequences to individuals, their families, and wider society.

Alcohol and drug use costs the taxpayer millions of pounds every year in dealing with the associated health problems, loss of productivity, children and adult social care costs and drug related crime and disorder. Problematic alcohol and drug use can be a pathway to poverty, lead to family breakdown, crime, debt, homelessness and child neglect.

Investing in a multi-agency response to address drug and alcohol harm has benefits across society. In Surrey, these efforts are delivered by the Combating Drugs Partnership (CDP) which was formed as a result of the government’s 2021 “From harm to hope” drug policy. Surrey’s CDP reports to the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Board (incorporating the Community Safety Board) through its sub-board, the Prevention and Wider Determinants of Health Delivery Board.

The Surrey Health and Wellbeing strategy focuses on Surrey’s Priority Populations (including those with alcohol/drug/serious mental health issues, experiencing homelessness and/or domestic abuse). The Strategy’s Index measures Surrey system’s progress against it.

The term “substance misuse” has been used throughout this JSNA chapter in keeping with the terminology used by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) and the Office for National Statistics (ONS). However, we recognise that the terminology may continue to evolve in response to increasing understanding of potentially stigmatising language.

The summary of findings below is based on publicly available data, mainly for the financial year 2021/22. Full details are in the main report.

Level of need in the population

In Surrey, the estimated prevalence rate of opiate and /or crack-cocaine use was lower than England and the South-East, but it is estimated that levels of unmet need (the number of people in treatment divided by the estimated prevalence of people using opiates and/or crack cocaine) are higher – Surrey 67.5% and England 57.9%. This data is currently being examined to understand the reasons for this difference.

Of all adults in treatment in Surrey, the most common reported substances were opiates, alcohol, and cannabis. This is slightly different from adults starting treatment in Surrey, where the most commonly reported substances were alcohol, cannabis and cocaine and it reflects that the population of opiate users is ageing. People who use opiates tend to be in treatment longer than most other substances, which reflects the ageing opiate user population.

Nearly a quarter of adults in Surrey reported drinking at increased or higher risk levels (over 14 units of alcohol a week), higher than England levels. In Surrey, levels of alcohol dependence are lower than England, but there has been a gradual increase in numbers in treatment and an increase in hospital related alcohol admissions, mainly for alcohol related liver disease. It is estimated that there are high levels of unmet need for alcohol treatment, at 74%, although this is similar to South-East and England.

For young people, nationally and in Surrey there has been a reduction in people in contact with substance use services. Of those young people in treatment, cannabis remains the most common reported substance with similar levels of use compared to England. This is followed by cocaine, ketamine, and benzodiazepines, all of which had higher rates of reporting than England. A higher proportion of young people commencing treatment for substances in Surrey reported that they had problems with alcohol compared to England. Surrey has a slightly higher proportion of state funded school suspensions and a higher proportion of permanent exclusions due to drugs and alcohol compared to England.

Who is at greater risk?

A range of risk factors can make people more susceptible to drug and alcohol related harm:

- Individual factors, such as mental health, health/disability, trauma, experience of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), employment /educational /housing /economic status and genetics.

- Interpersonal factors, such as prosocial relationships, peer influences and norms, family structure and functioning.

- Community factors, such as ease of access to drugs, economic and housing opportunity, marginalisation and social isolation /cohesion.

- Institutional factors such as accessibility of drug use services and generic helping services, exclusion, and discrimination.

People who experience severe and multiple disadvantage are in particular at increased risk of drug and alcohol related harm.

Impacts of substance misuse in Surrey

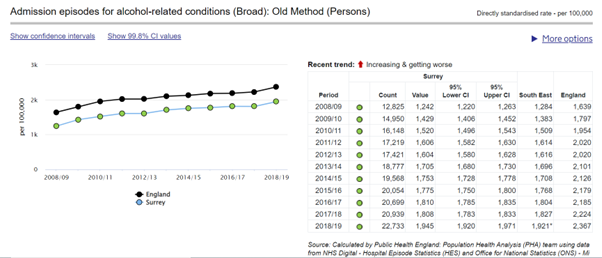

The rate of alcohol related hospital admissions has been increasing over the past ten years in England and Surrey. Overall, the rate of admissions is lower in Surrey than England, however there was a 43% increase in alcohol-related hospital admissions in Surrey between 2008/9 and 2018/19 and some boroughs have higher rates than England. Rates of hospital admissions for alcohol specific conditions for under 18-year-olds in Surrey were higher than England, in particular among girls.

The estimated national cost of the illicit drugs trade is over £19 billion annually. Nearly half of acquisitive crimes are estimated to be associated with drug use. Between 2021-22 over 5,000 drug offences were recorded in Surrey, with cannabis possession the highest drug related offence. This is one of the lowest rates nationally, but data should be treated with caution as it is based on proactive police enforcement activity.

Domestic violence and alcohol are key drivers for homicides. However, it is likely that drugs remain a factor as the scale of offences is not fully known.

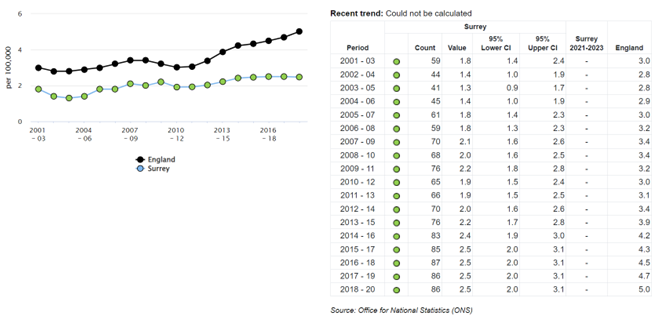

The rate of deaths from drug misuse in significantly lower in Surrey than England. The trend over the past ten years has been increasing for England, but with only a slight increase in Surrey. Men and individuals with a diagnosed mental health condition are more at risk.

Evidence base and prevention, treatment and recovery services

Every £1 spent on drug treatment saves £2.50 in costs to society. The substance misuse service system in Surrey includes prevention, treatment and recovery for both children and young people and adults. The aim is to work in an integrated way to ensure a seamless transition from one area to another for the benefit of the clients until they successfully complete their treatment journey. Healthy Surrey provides a full list of all Drug and Alcohol Services (adult and young people) in Surrey. All commissioned services follow National Institute of Clinical Excellence Guidance and Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (OHID)/Public Health England Guidance, these are listed in the main body of the JSNA.

Treatment for substance misuse

A major focus of the national policy drive on drugs is to increase numbers in treatment and reduce unmet needs. In 2021/22 there were 3,842 adults and 209 young people in treatment for drugs and/or alcohol misuse in Surrey. Most adults in treatment were for alcohol or opiate dependency. Waiting times for first treatment interventions in Surrey are good with very few adults waiting more than three weeks. The majority of treatment in Surrey takes place in community settings with only 1% of the adult treatment population attending residential rehabilitation. In line with national trends, since 2009 until the COVID pandemic there had been a decline in Surrey in people aged under 24 years old in structured treatment for substance use. Numbers increased from 2021/2 but have not returned to 2009 levels. All young people in Surrey had community-based treatment.

More men than women are in treatment for drugs and alcohol in Surrey (70% male for drugs, 57% male for alcohol). These gender ratios are similar to those seen in England.

Relative to England, a higher proportion of people in drugs and alcohol treatment in Surrey are of ‘White’ ethnicity; are recorded as having no disability; are in employment; experience no housing problem; are parents who live with their children; are smokers at start of treatment. Mental health needs are high among people entering treatment for drug use, with nearly 80% of females and nearly 70% of males having a mental health need. This difference is also seen among young people with 66% of females and 40% males under 18 years identified with a mental health need.

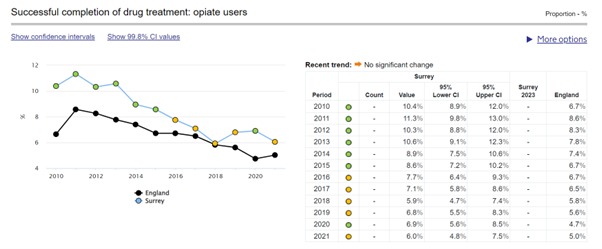

Adults in both drug and alcohol treatment in Surrey had higher rates of leaving treatment in an unplanned way than England. Compared with England, significantly lower numbers of people successfully engaged in community-based treatment within three weeks of release from prison in Surrey. ‘Successful completion’ of treatment is defined as non-representation within six months of treatment. However, substance misuse is a chronic, relapsing and remitting condition, and those who re-present to treatment may still be on their treatment journey, rather than ‘unsuccessful’. In this context, overall, in 2021/22 Surrey had higher rates of successful completion of treatment for drugs and non-representation within six months than England. However, the rate of successful completions for opiate treatment has declined since 2010 in Surrey and England. Successful completion rates for alcohol and non-opiate treatment in Surrey decreased, whereas in England they increased and a lower proportion of those in treatment in Surrey became abstinent from alcohol.

Themes from stakeholder engagement

Stakeholders such as mental health professionals, housing commissioners, education services, treatment providers, GPs, and the police were engaged by a combination of written feedback and attending meetings/asking for verbal feedback. Themes that emerged from their engagement included:

Prevention: Training and support for non-specialist services such as teachers and police would be helpful. Targeted prevention for particularly priority populations is important – such as looked after children, adult with care experience, and young carers. The increasing normalisation and use of cannabis should be addressed.

Person-centred approach: Building services around people’s needs rather than their diagnoses helps design better services. Outreach and support workers can help people navigate complex systems and avoid non-engagement and help maintain housing. Peer support and workers with lived experience are helpful. Trauma-informed care is important.

Substance misuse services: There is inconsistent investment in alcohol liaison services in acute settings. Residential rehabilitation is not available within county, and there is a lack of detoxification options for people in unstable housing situations. There is a need for more out of hours services, and increased awareness about one stop shop drop ins and warm spaces. Crisis cards with helpline numbers should be widely available.

Mental health: The most complex patients are the most likely to suffer from exclusion criteria when accessing services. The development of more in-reach mental health services could help provide support when people may be more receptive to addressing substance misuse issues.

Criminal Justice: Surrey could improve on test on arrest and use of Drug Rehabilitation Requirements (DRR) and Alcohol Treatment Requirements (ATR), and availability of naloxone. It is important to ensure there is capacity in the system for education and treatment if numbers are increased through proposed introduction of tougher consequences for drug possession.

Recovery: More support is needed for people leaving residential rehabilitation. Housing pathways to meet the needs of high-needs clients and appropriate placements may help prevent failed housing placement. People placed in emergency accommodation out of county may find it difficult to access support and treatment. More partnership with the Department of Work and Pensions could help improve employment opportunities.

Collaboration: Pro-active partnership working across services is important and may help address the challenges of information sharing between agencies. Examples of collaboration included use of shared joint clinic space in community hubs and use of joint local quality assurance guidelines.

Workforce: Frequent staff changes are a concern and may lead to a loss of organisational memory and understanding at a leadership level. More resources to develop the workforce may help address challenges of recruitment, especially of experienced staff within substance misuse services.

People with lived and living experience

The CDP commissioned the public involvement service (Luminus, also home to Healthwatch Surrey) to engage over the period of two years with people with lived and living experience and their families and friends and others affected by drugs and/or alcohol. Findings from the first two quarterly reports are contained in this JSNA and reflect direct feedback from carers, service users, and frontline staff. Findings provide insights into the public’s experiences and perceptions. and will evolve as further reports are collated.

A summary of themes and issues that were highlighted include:

Barriers to access: Stigma and perception of stigma are barriers, lack of awareness that self-referral is possible, perception of rigid processes that don’t work for all.

Communication and signposting: GPs and other frontline health staff may not be aware of services, or may not signpost to services.

Mental health and substance misuse: A perception of lack of support for the trauma that often underlies substance misuse; a perception of not being able to access mental health treatments while using substances; preferring different treatment methods to those on offer.

Continuity of care and establishing trust: Seeing different GPs each time makes it hard to build trust and can be triggering for patients; lack of knowledge of who can help with complex problems; perception of lack of follow-up.

Carers: Difficulties getting loved ones to engage with treatment; perception of lack of support for carers.

Service user feedback: Substance misuse services can be reassuring and can help people who misuse substances become sober.

Recommendations

Recommendations – rationale is set out in the main report

Prevention and early intervention

- Ensure ongoing high profile universal and targeted campaigns on reducing alcohol consumption among adults and young people.

- Embed and strengthen education for professionals and young people on substance use in school, and out of school, settings, including addressing normalisation of cannabis.

- Strengthen pathways between health, social services and drug services to identify and intervene early with vulnerable children and families.

Supporting people into treatment

- Tackle stigma related to substance use, to enable more people to seek treatment and build supportive communities. Encourage CDP partners to undertake stigma training.

- Explore the reasons for Surrey’s higher than England reported rates of unmet need in opiates and crack -cocaine.

- Continue to strengthen pathways between mental health and substance use services to ensure that people are able to access the right care where there is a dual diagnosis.

- Continue to review work by Solutions Research and CDP partners to optimise communication and referral pathways into substance misuse services in Surrey.

- CDP to investigate where there are discrepancies in Criminal Justice Intervention Teams (CJIT) data recording to ensure accurate data reporting.

- Increase engagement by Surrey prison leavers in community drug and alcohol treatment, increasing referrals from the criminal justice system including prisons and probation service. This includes reviewing the needs of male remand prisoners from Surrey in HMP Wandsworth (the main male remand prison for Surrey residents) to ensure effective pathways into treatment and recovery support.

- Optimise the introduction of Police custody ‘test on arrest’ and subsequent referral into treatment.

- Optimise the use of drug rehabilitation and alcohol recovery requirements/programmes within the criminal justice system.

- Understand and optimise referrals for young people from education settings and youth criminal justice settings.

Treatment journey

- Continue to explore reasons for, and reduce the rate of, people leaving treatment in an unplanned way before 12 weeks. Understand why more men than women leave treatment early in an unplanned way, including reviewing access to support.

- Work to understand treatment progress, including why Surrey appears to have a lower rate of successful completions for opiate treatment in adults compared with England.

- Work to understand and increase successful completions for alcohol treatment among adults.

People experiencing multiple disadvantage

- Continue to coproduce and improve engagement with people who experience multiple disadvantage and develop trauma informed practice, including learning from the Changing Futures programme and Multiple Disadvantage JSNA chapter.

- Improve understanding of the Care Act 2014 among organisations who work with vulnerable people such as people with multiple disadvantage and improve understanding of the importance of referring to adult social care for assessment at the earliest opportunity rather than waiting until the person is in crisis.

Wider services

- Continue to monitor the impact of pharmacy closures on harm reduction measures for service users.

- Review the smoking cessation offer to people who use substances as part of new smoking cessation contract with new provider.

Inequalities

- Better understand the interactions between protected characteristics and substance misuse in Surrey.

- Undertake a review to understand unmet need in Surrey, including if ethnic, gender, deprivation and disability differences of those in drug treatment in Surrey represent unmet need/barriers to access.

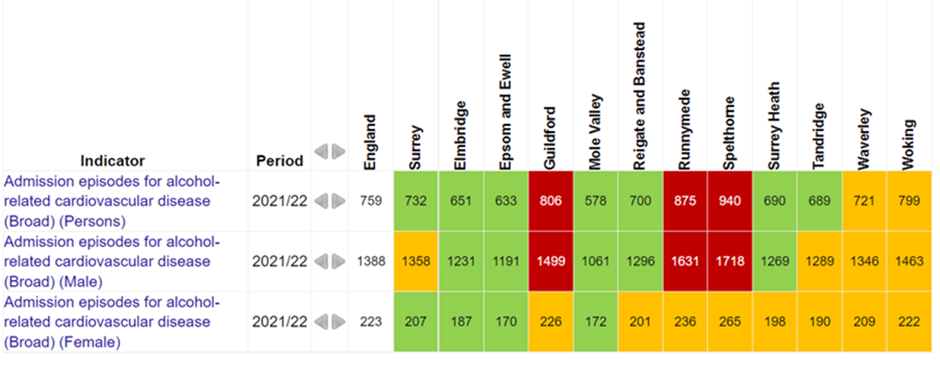

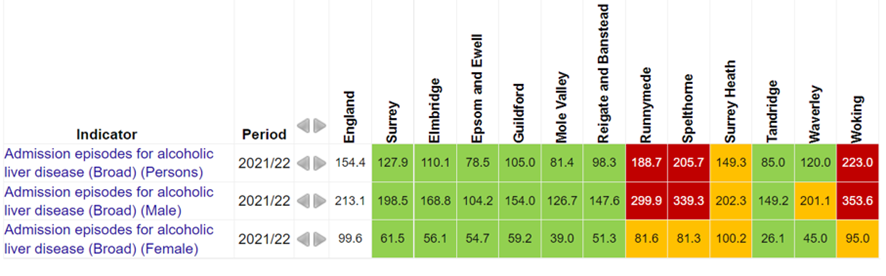

- Understand and address the higher rate compared to England of alcohol-related liver and/or cardiovascular disease in Runnymede, Spelthorne, Woking and Guildford.

Reducing deaths from drug misuse

- Continue to increase awareness and availability of naloxone within the community.

- Develop a partnership response to drug related deaths through a DARD (drug and alcohol-related deaths review system) approach.

- Undertake a 3-yearly drug-related death audit in partnership with Surrey Coroners’ Office to identify key themes.

- Build our intelligence of drug related deaths and overdoses, including promoting the use of the non-fatal overdose online reporting tool and implementing real-time surveillance of suspected drug-related deaths.

Strengthening recovery – wider determinants

- Review the appropriateness of housing options for people who misuse substances, including people with alcohol-related brain injury. JSNA Housing and Related Support | Surrey-i (surreyi.gov.uk)

- Improve access to accommodation within Surrey alongside treatment for homeless population, especially rough sleepers, to maintain continuity of care.

- Improve employment opportunities, linking employment support and peer support to Job-Centre Plus services, and deliver the roll-out of Individual Placement Support (IPS) from 2024.

- Optimise support for adult carers and young carers of people who misuse substances.

Information sharing and intelligence

- Improve data sharing among partners to understand longer term outcomes of treatment and recovery.

- Develop local outcomes framework to ensure on-going monitoring and review.

- Improve data exchange from ambulance providers via Surrey Office of Data Analytics (SODA) to ensure adequate monitoring of and understanding of naloxone treatment use in the community.

OHID data recommendations

- Include comparison with Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) nearest neighbours in commissioning support pack to allow regional comparisons to be drawn.

- Include quality outcomes in addition to process outcomes, which would help understand and evaluate local services.

- Include successful completions and non-representations at 12 and 18 months in addition to the current 6 months. This would give a more nuanced understanding of the patient journey and where to target improvements.

Introduction

The World Health Organisation defines drug misuse as the use of a substance not consistent with legal or medical guidelines. [1] The UK has seen an 80% increase in drug-related deaths since 2012. [2] Drug misuse costs society over £19 billion a year in dealing with associated health problems, lost productivity, adult and children’s social care costs and drug related crime and disorder. [3] Synthetic opioids caused a spike in drug-related deaths in 2023 and are thought to be becoming increasingly prevalent in local drug markets. [4]

According to NICE, problem alcohol use is defined as exceeding the Chief Medical Officer’s low-risk drinking guidelines (a maximum of 14 units a week over at least three days a week, and no alcohol during pregnancy). [5] In England, over 10 million people consume alcohol at levels above this. [6] These people are at increased risk of more than 200 medical conditions associated with alcohol consumption, including various cancers, liver disease, heart disease, and strokes. [6] According to the 2021 Health Survey for England, 28% of men and 15% of women drank at increasing or higher risk levels (over 14 units in the preceding week). [7] In 2017 to 2018 there were over 1.1 million hospital admissions related to alcohol. [6]

Scope and Methods

This needs assessment covers all adults and children and young people living in Surrey and has a particular focus on people in treatment for problematic substance use.

A mixed methods approach was used to inform this needs assessment, including:

- A review of relevant policies, guidance and evidence

- A review of publicly available data, most of which is from the 2023-24 Office for Health Improvement & Disparities’ Adult Drug Commissioning Support Pack [8], Adult Alcohol Commissioning Support Pack [9], and Young People’s Substance Misuse Commissioning Support Pack [10]. These data in turn are mostly obtained from National Drug Treatment Monitoring System data from 1st April 2021 to 31st March 2022.

- For adults, data are available for drugs and alcohol use separately, however for young people, data for drug and alcohol use are usually combined.

- Other sources of data, including police and crime data, are outlined in the national government guidance document: National Combating Drugs Outcomes Framework: supporting metrics and technical guidance (publishing.service.gov.uk) [11]

- Stakeholder insights are included from written and verbal feedback from attending meetings with partners including social care, mental health and other health services, housing, substance misuse service providers and GPs.

- The patient and public lived experience is captured via reports from Luminus.

- Draft recommendations were presented at meetings of CDP subgroups 1, 2, 3, and 4, and to wider stakeholders at a substance use event in September 2023. Their feedback was incorporated into the final recommendations.

Terminology

The term “substance misuse” has been used throughout this JSNA in keeping with the terminology used by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) and the Office for National Statistics (ONS). However, we recognise that the terminology may continue to evolve in response to increasing understanding of potentially stigmatising language.

National and Local Strategic Context

Dame Carol Black Review

In 2019, Professor Dame Carol Black led a two-part independent review of drugs commissioned by the UK Government. Part one was a broad assessment of the evidence on illegal drug supply into the UK and how criminals meet the demand of users, and part two made specific recommendations for improving prevention, treatment and recovery [12].

National Drug Policy

In December 2021, the Government published a formal response to the Dame Carol Black review. The 10-year drugs plan ‘From Harm to Hope’ [13] has three national strategic priorities:

1. Break drug supply chains

- targeting the ‘middle market’ – breaking the ability of gangs to supply drugs wholesale to neighbourhood dealers.

- rolling up county lines – bringing perpetrators to justice, safeguarding, and supporting victims, and reducing violence and homicide.

- restricting the supply of drugs into prisons – technology and skills to improve security and detection.

2. Deliver a world-class treatment and recovery system

- rebuilding the professional workforce.

- ensuring better integration of services.

- improving access to accommodation alongside treatment.

- improving employment opportunities.

- increasing referrals into treatment in the criminal justice system.

- keeping prisoners engaged in treatment after release.

3. Achieve a generational shift in demand for drugs

- preventing the onset of drug use among children and young people.

- delivering school-based prevention and early intervention.

- supporting young people and families most at risk of substance misuse.

- reducing the demand for drugs among adults.

Local strategic context

Surrey’s Combatting Drugs Partnership (CDP) reports to the Surrey Health and Wellbeing Board through the Prevention and Wider Determinants of Health Delivery Board. The Surrey Health and Wellbeing Strategy focuses on its Priority Populations (including those with alcohol/drug and/or serious mental health issues, experiencing homelessness and /or domestic abuse). There are 14 outcomes (including ‘substance use is low’ and ‘the needs of those experiencing multiple disadvantage are met’) in order to achieve its mission of reducing health inequalities so no one is left behind. The Strategy includes a set of principles for working with communities to support empowered and thriving communities. The Strategy’s Index measures Surrey system’s progress against it.

In June 2022, the Government published guidance for local partners [14] to sit alongside the national ‘From Harm to Hope’ drugs policy outlining the structures and processes through which local partners in England should work together to reduce drug-related harm. Successful delivery of the government’s drugs strategy relies on co-ordinated action across a range of local partners including in enforcement, treatment, recovery and prevention. The guidance sets out in more detail the drugs strategy vision for Combating Drugs Partnerships in each locality.

In May 2023, the guidance for local partners was accompanied by an updated National Combating Drugs Outcomes Framework [11]. This document sets out metrics which form a single mechanism to measure progress across central government and in local areas in tackling misuse of drugs and associated negative outcomes.

The three strategic outcomes are:

- Reducing drug use.

- Reducing drug-related crime.

- Reducing drug-related deaths and harm.

The government aims to deliver these strategic outcomes via intermediate outcomes (also mentioned above in “National Drug Policy” section):

- Reducing drug supply.

- Increasing engagement in treatment.

- Improving recovery outcomes.

Surrey Combating Drugs Partnership

As per Government guidance for local partners, the Surrey Combating Drugs Partnership (CDP) Board was launched in September 2022 to drive the priorities highlighted in the Dame Carol Black Review and national 10-year drugs plan ‘From Harm to Hope’.

In addition, four subgroups have been established to drive forward delivery plans focusing on:

- Breaking drug supply chains;

- World class treatment and recovery system;

- Achieving a generational shift in demand for drugs;

- Reducing alcohol and tobacco related harm.

National drug and alcohol use patterns

National Drug Use patterns

Approximately 1 in 11 adults aged 16 to 59 years (3 million adults) and 1 in 5 adults aged 16 to 24 years (1.1 million adults) reported drug use in the year ending June 2022. There was no change compared with the year ending March 2020. [6]

In the year ending June 2022, 2.7% of adults aged 16 to 59 years and 4.7% of adults aged 16 to 24 years reported Class A drug use; a significant decrease from the year ending March 2020 when this was 3.4% and 7.4%, respectively. [15]

There were no changes in drug use for the majority of individual drugs in the year ending June 2022 compared with the year ending March 2020, except for ecstasy and nitrous oxide; prevalence of ecstasy use fell from 1.4% to 0.7% in adults aged 16 to 59 years and from 4.0% to 1.1% in adults aged 16 to 24 years while prevalence of nitrous oxide use fell from 2.4% to 1.3% for adults aged 16 to 59 years and from 8.7% to 3.9% for adults aged 16 to 24 years. [15]

Decreases in the use of Class A drugs, ecstasy and nitrous oxide may have been a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and government restrictions on social contact. [15]

In the year ending June 2022, 2.6% of adults aged 16 to 59 years reported being frequent users of drugs (using them more than once a month in the past year); this was similar to the year ending March 2020 (2.1%). [15]

Cannabis remains the most used drug in England and Wales since estimates began in 1995. [15] 7.4% and 16.2% of adults aged 16 to 59 years and 16 to 24 years, respectively, reported having used the drug in the last year; a similar level to the year ending March 2020 and the year ending March 2012; however, levels are much lower compared with the year ending December 1995. [15]

In England in 2021, 10% of school pupils thought it was okay to try cannabis to see what it’s like, and 6% thought it was okay to take cannabis once a week. These figures have remained at similar levels since 1999. [16]

Synthetic opioids

Illicit fentanyls and isotonitazene are strong opioids which are more potent than heroin and can be mixed into heroin. They caused spikes in drug-related deaths in England in 2017, 2021 and 2023. [4]

Synthetic opioids are thought to be becoming increasingly prevalent in local drug markets. There are concerns that synthetic opioids may start to be incorporated into non-opioid drugs such as cocaine, benzodiazepines, and synthetic cannabinoids, unknown to people who use these drugs. [4]

National alcohol use patterns

Alcohol misuse is drinking in ways which are harmful, or a dependence on alcohol. Alcohol is a leading cause of premature death in England. 20,970 alcohol related deaths were registered in England in 2021, 38% of which were due to chronic liver disease. [17] Alcohol sales and the amount that people drink increased from the 1980s until reaching a peak in 2008 and declining slightly since then. [6] Some of this decline is due to more adults choosing to be teetotal, as well as fewer young people under the age of 18 drinking alcohol. However, there is large variation in drinking behaviour across different groups. It is largely the people who already tend to drink less that are cutting back, while many of those who are at high risk of health conditions, because they drink heavily, are drinking more now than they did previously. [5]

Risk factors that make people susceptible to drug and alcohol related harm

There are many factors which lead to increased risk of drug related harm. It can be associated with type of drug used (including the forms, routes of administration, amount consumed, context of use, and adulterants) and individual characteristics pertaining to the user (including genetic factors, mental, physical and social morbidities). The harm is also significantly influenced by policy and practice responses to drug use, social /socioeconomic factors, environmental factors, and access to education, employment and recreation. [18]

Specific set of risk factors can make some individuals more vulnerable to the harms associated with drugs. A Drug Misuse Prevention Review has identified following as examples of risk factors [19]:

- Individual: e.g., mental health /well-being, health /disability, trauma, experience of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), employment /educational /housing /economic status and genetics.

- Interpersonal: e.g., prosocial relationships, peer influences and norms, family structure and functioning.

- Community: e.g., ease of access to drugs, economic and housing opportunity, marginalisation and social isolation /cohesion.

- Institutional: e.g., accessibility of drug use services and generic helping services, exclusion, and discrimination.

- Policy: e.g., housing, employment, education, health and social policy and drugs legislation.

- Macro social system: e.g., population mobility and social inequality.

Who is more at risk? – vulnerable groups

Identification of vulnerable groups can help prioritise resources and ensure we do not discriminate against any groups. However, it is important to note that vulnerability potentially associated with a particular cohort does not automatically lead to vulnerability. Focus solely on the characteristics of specific cohorts can add to the stigma associated with drugs. Therefore, considering risk factors, contexts and behaviours which may make individuals vulnerable to drug use is a more effective approach.

The observed prevalence of past year use (April 2020 to March 2021) of any drug by people aged 16 and over in a Crime Survey of England and Wales was [19]:

- Higher among those unemployed (12.2%) than those economically inactive (7.9%) or employed (5.8%).

- Higher among those who identified as bisexual (11.1%) than those identifying as gay/lesbian (8.8%) or heterosexual (6.5%).

- Higher among those with a disability (8.6%) than among those without (6.1%).

- Higher amongst those in financial difficulty (12.8%) than those financially stable (6.7%).

- Lowest amongst those living in the least deprived areas.

- Higher amongst those who had experienced violence (14.3%) than those who had not (6.3%).

Vulnerability to alcohol misuse can be categorised as societal vulnerability factors or individual vulnerability factors [20].

Societal factors include:

- Alcohol pricing, availability, regulation.

- Drinking context.

- Socio-economic status.

- Culture.

Individual factors include:

- Mental health.

- Homelessness.

- Gender.

- Age.

The following cohorts of people are also at increased risk of engaging in drug and / or alcohol misuse and developing a dependency (including moderate dependency) [18]:

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (LGBT).

- Black Minority Ethnic Groups.

- Gypsy, Roma, Travellers (GRT).

- Those using prescription or over the counter (OTC) and prescription medicines.

- Those in the Criminal Justice System.

Multiple Disadvantage

People who experience severe and multiple disadvantage are at increased risk of alcohol -related harm including alcohol dependence. People facing multiple disadvantage experience a combination of concurrent problems, and for many their circumstances are shaped by long-term experiences of poverty, deprivation, trauma, abuse, and neglect. Many also face racism, sexism, and homophobia. (About Multiple Disadvantage – MEAM) [21] These inequalities intersect in different ways, manifesting in a combination of experiences including substance use, mental ill health and/or neurodivergent challenges, homelessness, domestic abuse and contact with the criminal justice system. The health inequalities and challenges this population face substantially increases their risk of the early onset of chronic health issues, shortened healthy life expectancy and premature death. [20]

In 2024, Surrey will publish a JSNA chapter on Multiple Disadvantage which will provide significant data and insight into adults, children and young people experiencing multiple and concurrent challenges, including drug and alcohol related need.

Drug and alcohol use in Surrey and its impact

Prevalence of adult opiate and crack cocaine use in Surrey

In Surrey, in 2019/20, the estimated rate of opiate and/or crack cocaine use was 5.0 per 1000 population aged 15 to 64. This was lower than the estimated England rate of 9.5 per 1,000 and the South East rate of 6.6 per 1,000. [8]

For opiates only, Surrey’s estimated prevalence rate was 2.3 per 1000, which was lower than England’s rate of 4.6 per 1000, and the South East’s rate of 2.9 per 1000. For crack-cocaine use, Surrey’s rate was 0.8 per 1000 population, which was lower than England’s rate of 1.3 per 1000, and the South East’s rate of 0.9 per 1000. For both opiates and crack, Surrey’s rate was 1.9 per 1000, England’s rate was 3.6 and the South East region’s rate was 2.8 per 1000. [8]

118 people were identified as homeless with a drug dependency need in Surrey in 2021/22. [22]

Estimated unmet need for Surrey adults who use opiates and crack cocaine

Unmet need is the proportion of estimated opiate and crack cocaine users who are not currently in treatment. In 2021/22, Surrey had higher unmet need than the South East region and England as per table 1 [23]:

Table 1: Unmet need for opiate and crack cocaine users in 2021/22 in Surrey

| Surrey (range), n = prevalence estimate | South East region (range), n = prevalence estimate | England (range), n = prevalence estimate | |

| Opiate and/or crack users | 66.2% (60-71%) N = 3,721 |

58% (54-61%), n = 36,553 | 57.4% (54-60%), n = 341,032 |

| Opiate users only | 64.8% (58-70%) N = 1,712 |

59.7% (56-63%), n = 16,014 | 58.2% (55-61%), n = 164,279 |

| Crack users only | 89.3% (86-91%) N = 571 |

85.6% (84-87%), n = 5,055 | 84.9% (83-86%), n = 47,168 |

| Opiates and crack users | 58.6% (52-64%) N = 1,438 |

47.3% (43-51%), n = 15,484 | 46.3% (43-50%), n = 129,584 |

There are some caveats around these figures on unmet need. People in Surrey who use both opiates and crack cocaine (OCU) have a statistically significantly higher unmet need than the South East region and England. The confidence intervals for the other groups of substance users overlap, meaning the apparent differences between the other groups may be due to chance. The apparent variation in unmet need for OCU between Surrey and the South East and England is being investigated.

Prevalence of hepatitis C in people who inject drugs

In 2021/22, of adults in treatment in Surrey, 21% had a positive hepatitis C antibody test, the same proportion as in England. [24]

Prevalence of other drug use in Surrey adults

The most common substances for all adults in treatment in 2021/22 were opiates, alcohol and cannabis. The most common substances reported by all adults starting treatment in 2021/22 were alcohol, cannabis and cocaine. This reflects known trends in reductions in people starting to use opiates over time, and an ageing population of opiate users.

In 2021/22, the most commonly cited problem substances reported by all adults in treatment for problems with all drugs in Surrey, compared with England can be seen in Table 2:

Table 2: the most commonly cited problem substances reported by all adults in treatment for problems with all drugs in Surrey and England in 2021/22

| Surrey, n (%) | England, n (%) | |

| Opiates | 1,228 (56%) | 140,558 (69%) |

| Alcohol | 769 (35%) | 58,260 (28%) |

| Cannabis | 746 (34%) | 57,355 (28%) |

| Crack cocaine | 661 (30%) | 77,728 (38%) |

| Cocaine | 546 (25%) | 34,837 (17%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 195 (9%) | 14,823 (7%) |

| Amphetamines other than ecstasy | 56 (3%) | 7,400 (4%) |

| Hallucinogens | 50 (2%) | 2,590 (1%) |

| Ecstasy | 24 (1%) | 1,115 (1%) |

| New psychoactive substances | <5 (0%) | 2,331 (1%) |

In 2021/22, the most commonly cited problem substances reported by all adults starting treatment for problems with all drugs in Surrey, compared with England can be seen in Table 3:

Table 3: Most commonly cited problem substances reported by all adults starting treatment for problems with all drugs in Surrey and England, 2021/22

| Surrey, n (%) | England, n (%) | |

| Alcohol | 467 (44%) | 28,541 (37%) |

| Cannabis | 465 (44%) | 28,236 (37%) |

| Cocaine | 396 (38%) | 21,298 (28%) |

| Opiates | 303 (29%) | 33,213 (43%) |

| Crack cocaine | 202 (19%) | 23,543 (31%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 63 (6%) | 3,848 (5%) |

| Hallucinogens | 40 (4%) | 1,666 (2%) |

| Amphetamines other than ecstasy | 33 (3%) | 2,660 (3%) |

| Ecstasy | 19 (2%) | 555 (1%) |

| New psychoactive substances | <5 (0%) | 1,116 (1%) |

Prescription-only and over-the-counter medication use in Surrey adults

In 2021/22, 9% of adults in treatment reported illicit use of prescription only medicines/over the counter medications (POM/OTC), and this figure was also 9% in England. 7% of adults in treatment in Surrey reported non-illicit use of these medications, compared with 4% in England.

Prevalence of alcohol use in Surrey adults

In 2015-2018 (the most recent data available), 23.9% of adults in Surrey reported drinking 14 or more units of alcohol per week, statistically significantly higher than England’s proportion of 22.8%. In 2015-2018, 9.9% of Surrey adults reported alcohol abstinence, statistically significantly lower than 16.2% in England. This may be because Surrey has a lower proportion of ethnicities who are culturally associated with lower alcohol consumption, compared with England as a whole. [25]

There has been a gradual increase in numbers in treatment for alcohol dependence in Surrey from 1,479 in 2018/19 to 2,178 in 2021/22.

From 2008/9 to 2018/19 there was an increase of 43% in alcohol-related hospital admissions in Surrey.

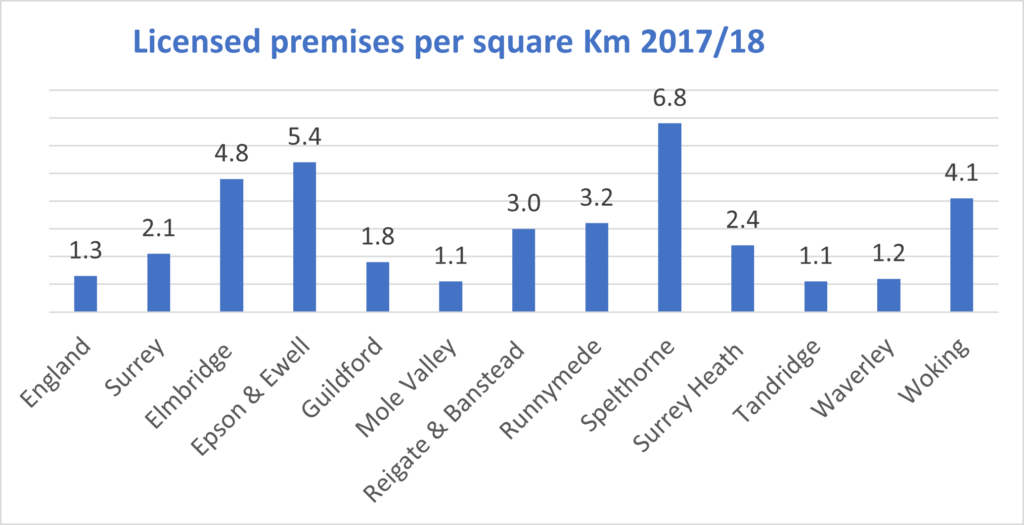

In 2017/18, Spelthorne and Woking were in the top four Surrey boroughs with most licensed premises per square kilometre. Spelthorne and Woking are also two of the three boroughs with the highest rate of hospital admissions for alcohol-related liver disease.

Figure 1: Surrey premises licensed to sell alcohol per square kilometre 2017/18

Estimated unmet need for alcohol use in Surrey adults

In 2021/22, Surrey’s level of unmet need for alcohol treatment was estimated at (73.9%), based on comparing prevalence estimates of adults who have an alcohol dependency problem and numbers in treatment. This is lower compared to unmet need in the South East region at 81.7%, and England’s rate at 80.5% [23]. However, due to overlapping confidence intervals, these rates may not be statistically significantly different.

Prevalence of drug use in Surrey young people

There were 11,326 young people (people under the age of 18) in contact with drug and alcohol services in England between April 2021 and March 2022. This is a 3% increase from the previous year (11,013) but a 54% reduction in the number in treatment since 2008 to 2009 (24,494). Variations in numbers in treatment over the years could indicate wider secular trends of changing substance misuse patterns among younger people, or potential unmet need, or a combination of both and more factors.

In 2021/22 in Surrey, there were 209 people aged under 25 in community structured treatment for young people in Surrey. Cannabis remains the most common reported substance in Surrey young people (79%), which is similar to levels in England (83%).

The next most commonly reported substances were cocaine (22% in Surrey, 12% in England), ketamine (11% in Surrey, 5% in England), benzodiazepines (7% in Surrey, 4% in England), nicotine (7% in Surrey, 11% in England), ecstasy (6% in Surrey, 7% in England), other drugs (6% in Surrey, 3% in England) and other opiates including codeine (2% in Surrey and England).

Prevalence of alcohol use in children and young people in Surrey

In 2021/22, 54% of young people in treatment in Surrey said they had problems with alcohol compared with 47% in England.

In the 28 days prior to commencing treatment for substances, for under-18s in 2021/22, Surrey had higher proportions of heavier drinkers than England as seen in the figure below:

Table 4: Number and proportion of young people (under 18) in treatment by drinking level units for Surrey and England, 2021-22

| Units | Local, n (% of young people) | England, n (% of young people) |

| 0 | 40 (29%) | 4,414 (46%) |

| 1-199 | 82 (59%) | 4,508 (47%) |

| 200-399 | 10 (7%) | 409 (4%) |

| 400-599 | <5 (<5%) | 119 (1%) |

| 600-799 | <5 (<5%) | 43 (0%) |

| 800-999 | 0 (0%) | 24 (0%) |

| 1,000+ | 0 (0%) | 27 (0%) |

| Total | 139 | 954 |

Children looked after with drugs as a factor

Children looked after are a vulnerable group who are at higher risk of substance misuse. Nationally, 3% of young people in community structured substance misuse treatment are children looked after compared with 1% in Surrey (n=8) [26]. This may be a true difference related to a higher proportion of children looked after nationally than in Surrey, or due to data recording/reporting issues.

In Surrey in the year ending 31st March 2022, in factors identified at the end of assessment of a child in need by children’s social care, concerns about drug misuse about the parent were present in 1049 cases and concerns about drug misuse about the child were present in 466 cases. [26]

School exclusions and suspensions that are drug and alcohol related

The school environment is seen as being a protective factor against the uptake of risk-taking behaviours including substance use. Being excluded and/or suspended from school can have a negative effect on young people and increase their vulnerability to problematic substance use and drug-related exploitation.

In Surrey in 2020/21, of the 6,125 total number of state-funded school suspensions, 229 (4%) were related to drugs and alcohol (compared with 3% nationally). [27] Of 84 permanent exclusions from Surrey schools in 2020/21, 9 (11%) were related to drugs and alcohol (compared with 407, or 8% nationally). [27]

Drug and Alcohol related hospital admissions and deaths in Surrey

Hospital admissions due to drug-related poisoning in adults

In 2021/22, hospital admissions for drug-related poisoning were statistically significantly lower in Surrey than in England – 32.3 per 100 000 compared with England’s rate of 42.9 per 100 000. The trend in both Surrey and England is that drug-related poisoning rates have been decreasing since 2018/19.

Hospital admissions due to alcohol in adults

In 2020/21, the directly standardised rate of admission episodes for alcohol-specific conditions in Surrey adults was statistically significantly lower than in England (455 per 100 000 compared with 587 per 100 000). However, some Surrey boroughs have rates above the national average.

The rate of admission episodes for alcohol-related cardiovascular disease is above the national average in Guildford, Runnymede and Spelthorne, as seen in figure 2:

Figure 2: Admission episodes for alcohol related cardiovascular disease (broad), 2021/22, persons

The rate of admission episodes for alcohol-related liver disease is above the national average in Runnymede, Spelthorne and Woking as seen in figure 3:

Figure 3: Admission episodes for alcohol related liver disease (broad), 2021/22, persons

The rate of alcohol-related admission episodes has been increasing over the past ten years in England and Surrey.

Figure 4: Admission episodes for alcohol-related conditions [17]

Hospital admissions due to drug poisoning in young people

In 2018-19 and 2020-21 Surrey’s hospital admissions due to substance misuse (directly standardised rate per 100 000 population of 15-24 year olds) was lower than England but this was not statistically significant (76 per 100 000 in Surrey and 81 per 100 000 in England).

Hospital admissions due to alcohol in young people

In 2018-19 and 2020-21, the directly standardised rate of admission episodes for alcohol-specific conditions in Surrey for people aged < 18 years old was higher than in England, especially in women <18 years old. The overall difference was not statistically significant (33 per 100 000 compared with 29 per 100 000).

Naloxone provision

The use of naloxone is important in reducing opioid-related deaths. A lower proportion of eligible Surrey adults in opiate treatment were issued with naloxone (10%) than adults in England (40%). However, in Surrey there is access to naloxone through community services which may be a preferred collection option for individuals in treatment.

Drug related deaths in adults

Between 2018-2020 there were 86 drug related deaths in Surrey and the directly standardised rate of deaths from drug misuse in 2018-20 was statistically significantly lower than England at 2.5 per 100 000 compared with England’s rate of 5 per 100 000. This trend has been rising in England over the past 10 years and rising slightly in Surrey.

Figure 5: Drug related deaths [28]

Drug-related deaths audit

In 2021, Surrey commissioned a drug-related deaths audit which reviewed 151 drug-related deaths in Surrey between 2017 and 2020. The findings showed that:

- 2/3 of deaths occurred in males.

- The average age of drug related deaths in Surrey residents is 45 years.

- Over 1/3 of individuals lived alone, which is higher than the Surrey average.

- 1/10 were in a relationship.

- 3/10 were unemployed.

- 2/3 of individuals had a diagnosed physical health condition.

- 3/4 individuals had a diagnosed mental health condition.

- Most individuals had more than one substance present at the time of death, and 38% had five or more substances present.

- 3/4 deaths had opiates present.

- Naloxone was only used in 4 of the 91 deaths where opiates were present.

Death by suicide audit

In 2021, a suicide audit was published examining 258 deaths by suicide in Surrey between 2017 and 2020. 57% of people who died by suicide acknowledged either alcohol or substance use before death, mostly long-established alcohol use and/or drug misuse. Only 3% of individuals who died by suicide were in contact with specialist substance misuse services prior to death.

At post-mortem, drugs and/or high levels of alcohol were found in the system of the deceased in 57% of cases, suggesting that half of all cases were under the influence of drugs/alcohol at the moment they took their own life.

Deaths for adults in drug treatment

Surrey’s rate of adults who died within a year of completing drug treatment was 0.8% in 2021/22 compared with England’s rate of 1.3%. The majority of these deaths in Surrey and England were in adults being treated for opiate use. The trend over the past decade has remained around the same level for the past decade. [28]

Alcohol specific deaths in adults

In 2021, alcohol-specific mortality was statistically significantly lower in adults in Surrey than in England (directly standardised rate of 8.1 per 100,000 in Surrey, compared with 13.9 per 100,000). The trend has remained around the same level for the past decade.

Drug and alcohol related crime

The estimated total national cost of the illicit drugs trade, taking into account health and criminal justice costs together, is over £19 billion a year. This is more than double the estimated value of the illicit drugs market itself. [29] 86% of the drug-related costs to individuals and society are concentrated in the markets for heroin and crack cocaine.

National increases in serious violence over recent years are believed to be in part due to drugs. The Children’s Commissioner estimates that 27,000 children in England and Wales identify as gang members. [29]

Neighbourhood crimes

Nearly half of acquisitive crimes (excluding fraud) are estimated to be associated with drug use [30]. In 2021/22, 9,284 neighbourhood crimes were recorded in Surrey, these include domestic burglary, personal robbery, vehicle offences and theft from the person.

Proven reoffending

Surrey’s reoffending rate for January 2021-December 2021 was 20.3%, compared with a rate of 21.6% in England and Wales for the same time-period. [31]

Drug trafficking and possession

Between January 2021 and December 2022, a total of 5,305 drug offences were recorded in Surrey. 4016 (76%) of these were possession offences. 633 (24%) were supply offences. Cannabis possession was the highest drug offence type (3,208, or 80%) followed by cocaine possession (383, or 10%). [32].

Drug offences

Surrey had the 14th lowest rate nationally of drug offences per 10,000 population between June 2019 and March 2022, but this data should be interpreted with caution as this indicator is almost wholly based on proactive police enforcement activity. [33]

Hospital admissions for assault by sharp object

For Surrey for 2020/21, there were 15 hospital admissions aged 0-24 for assault by sharp objects, and 15 hospital admissions for people aged 25+ for assault by sharp objects. [34]

Homicides

There is a correlation between illicit drug use and homicides. From June 2019 to March 2022, Surrey’s homicide rate was 4 per million population, compared with the national average of 10.7 per million population. [33]

The latest data published by ONS’s Homicide Index reports that in the last three years, 28% of homicide suspects and 32% of homicide victims were thought to be under the influence of alcohol and/or illicit drugs at the time of the homicide. 45% of homicide suspects were known to be drug users and 29% to be drug dealers. [33]

Domestic violence and alcohol are key drivers for homicides in Surrey. It is likely that drugs are also a key driver for domestic violence in Surrey, particularly as, since many offences involve survivors who may find it difficult to take part in investigations, the scale of offences is not fully known. [35] A serious violence needs assessment is currently being produced.

Evidence base for interventions

Evidence shows that investing in drug treatment reduces social costs associated with drug misuse and dependence:

- There is evidence that community-based needle and syringe programs are associated with reduced rates of HIV and hepatitis C infection in the target population. [36]

- Opioid substitution treatment (usually methadone or buprenorphine) is associated with reduced drug use, injecting and mortality, as well as reduced crime and reduced offending proportionate to the time spent in treatment. [36]

- Specialist drug treatment services in England are associated with reductions in offending. [36]

- The evidence for psychosocial intervention treatments is more mixed. [36]

- It is estimated that the net benefit-cost ratio is £2.5 in cost savings for every £1 spent on treatment. [36]

The evidence-based interventions for alcohol use disorders encompass a range of strategies proven effective for reducing alcohol related harm. The interventions include:

- The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) is the gold standard screening tool used for identifying individuals at risk of alcohol use disorders. This is a cost-effective method for early detection of alcohol-related problems and can be applied in various settings, including healthcare. Studies indicate that using AUDIT for screening and subsequent intervention can lead to significant improvements in patient’s alcohol consumption patterns and overall health outcomes.

- Identification and Brief Advice (IBA and Extended Brief Advice (EBA) are evidence-based interventions that show efficacy in addressing alcohol use disorders. IBA typically involves a short screening using tools like AUDIT, followed by brief, structured advice on reducing alcohol consumption. This approach is particularly effective in primary care and community settings. EBA extends this model by providing more in-depth counseling and follow-up sessions. Studies have shown that both IBA and EBA can lead to significant reduction in alcohol consumption among moderate-risk drinkers.

- Identification and brief advice in primary care can save the NHS up to £27 per patient, per year.

- Small-scale evaluations show that assertive approaches working with High Impact Complex Drinkers can deliver reductions in service use, savings to the healthcare system and reducing alcohol related harm.

- At the policy level, minimum unit pricing, taxation and regulation of the availability of alcohol, have proven to be effective interventions reducing alcohol related harm.

- Alcohol public awareness campaigns and educational programmes are crucial in raising awareness, changing behaviours, and ultimately reducing alcohol related harm in the community.

- Young people’s drug and alcohol interventions result in £4.3 millions health savings and £100 millions crime benefits per year.

- Alcohol treatment reflects a return on investment of £3 for every pound invested.

Commissioned services follow best practice and guidance as detailed in the following NICE guidelines:

Drug misuse prevention: targeted interventions NICE guideline [NG64] Published: 22 February 2017 [37]

Drug misuse in over 16s: opioid detoxification Clinical guideline [CG52] Published: 25 July 2007 [38]

Drug misuse in over 16s: psychosocial interventions Clinical guideline [CG51] Published: 25 July 2007 [39]

Coexisting severe mental illness and substance misuse: community health and social care services NICE guideline [NG58] Published: 30 November 2016 [40]

Drug use disorders in adults Quality standard [QS23] Published: 19 November 2012 [41]

Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking (high-risk drinking) and alcohol dependence Clinical guideline [CG115] Published: 23 February 2011 [42]

Alcohol-use disorders: prevention Public health guideline [PH24] Published: 02 June 2010 [43]

Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis and management of physical complications Clinical guideline [CG100] Published: 02 June 2010 Last updated: 12 April 2017 [44]

Alcohol and drug misuse prevention and treatment guidance Office for Health Improvement and Disparities Published 20 December 2017 Last updated 7 March 2023 [45]

Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management Department of Health and Social Care Published 14 July 2017 Last updated 15 December 2017 [46]

Service user involvement: A guide for drug and alcohol commissioners, providers and service users Public Health England 2015 [47]

New psychoactive substances (NPS) in prisons – A toolkit for Prison Staff Public Health England 2016 [48]

Substance misuse services for men who have sex with men involved in chemsex Public Health England 2015 [49]

Prevention, treatment and recovery services in Surrey

Prevention services for adults

Surrey has a range of both primary and secondary prevention substance misuse interventions including:

Primary prevention

- Surrey residents have free access to a screening online tool (Drink Coach) which uses the AUDIT score to categorise people into varying levels of risk of harm from alcohol Alcohol Test | DrinkCoach — DrinkCoach.

- Surrey County Council promotes the following campaigns: Dry January, Alcohol awareness week in July and Sober October.

- Surrey County Council has mapped Surrey neighbourhoods with high rates of alcohol-related admissions, and provides focused information to these neighbourhoods about the Healthy Surrey website, and signposts to services.

- Adopting the Making Every Contact Count (MECC) approach, including training the wider workforce including health and care providers, criminal justice, probation, job centres, adult social care to identify individuals at risk of harm from alcohol using the AUDIT score and signposting them to help.

Secondary prevention

- Harm-reduction approaches within community and outreach settings (as people who engage in treatment have a lower risk of drug related death).

- A help line for individuals seeking advice about drug and alcohol use.

- Naloxone provision.

- Surrey County Council commissions workers who are integrated into different services such as probation, and Women’s Support Centre to identify individuals at an earlier stage in their drug and alcohol use to prevent long term harm.

- Surrey substance misuse treatment services provide training for professionals in housing, police and health, to identify individuals who would benefit from help and provide brief interventions.

- Surrey County Council supports the Surrey Liver Health Check Programme identify people at early stages of liver disease and signposts to services.

- Surrey County Council has commissioned training sessions via Alcohol Change UK for alcohol treatment workers about various issues affecting people who misuse alcohol.

Community drug and alcohol services for adults

i-access is the main service commissioned by Surrey Public Health for adults aged over 18 years who use drugs and/or alcohol. It is led by the Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SABP) who subcontract VIA (formerly known as Westminster Drug Project) for certain elements of the contract.

i-access provide both pharmacological and psycho-social treatment. i-access is co-located with Adult Social Care Substance Misuse Team, who provide assessment under the Care Act, lead on Adult Safeguarding and assess for suitability for residential rehabilitation. Surrey Public Health and Adult Social Care each funds part of rehabilitation.

i-access services include support groups for:

- Abstinence preparation.

- Non abstinence.

- Peer mentoring.

- Recovery café.

- Relapse prevention.

- SMART recovery.

- Women’s group.

- Managing anxiety group.

- Alcohol education group.

i-access services include detoxification services for home detoxification and community detoxification (sometimes known as “ambulatory detoxification”). i-access can refer into inpatient detoxification if appropriate.

Adult Social Care Substance Misuse Team

In Surrey, there is a standalone Substance Misuse Social Care Team which works in partnership with health substance misuse treatment delivery (i-access). The Substance Misuse Social Care Team is county wide and comes under the umbrella of Specialist Mental Health Services and is directly accountable to Surrey County Council Adult Services. ASC Substance Misuse have separate responsibilities but are collocated and work collaboratively with i-access. They also receive referrals through Adult Social Care and work with service users who may not be receiving support from treatment services.

Within this co-located system, health undertake clinical work and treatment whilst social care focus on social care, such as:

- Care Act (2014) compliance; Safeguarding; Social care assessments (Care Act 2014) and reviews; Carers (Care Act 2014); Support planning and provision of packages of care to support care and support needs; Crisis intervention; Mental capacity assessment; Wellbeing and prevention.

- Social Care manage the rehabilitation pathway via assessment, provision and support for rehabilitation programs through our social care processes and RAP (Rehabilitation Assurance Panel).

- Offer joint working and training to mental health, hospital and general locality social care services.

- Embedded in the Surrey County Council Health and Wellbeing Multiple Disadvantage agenda and from this they offer wider training in relation to social care services.

Surrey Public Health also commission services that are part of the long-term recovery agenda. These services include:

- Telephone helpline – free and confidential service for those experiencing problems with substance use and their families (Surrey Drug and Alcohol Care)

- Telephone counselling for those who have experienced a non-fatal overdose, and those bereaved due to a drug-related death (Surrey Drug and Alcohol Care)

- Supported accommodation for adults in recovery from drugs and/or alcohol (Transform Housing and HomeGroup)

- Recovery workers to work specifically with women at risk of engagement with the criminal justice system, based within Surrey’s Women’s Support Centre

- Cuckooing service (co-commissioned with the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner), supporting vulnerable adults at risk of exploitation due to drug dealing (Catalyst)

- Naloxone and needle exchange provision and training, offering support to organisations working with vulnerable adults (Guildford Action)

- Advocacy service to support those engaging in treatment for substance use (POhWER)

- Public Involvement service for those impacted by substance use (Luminus)

Community services for people experiencing multiple disadvantage

Lankelly Chase’s report, ‘Hard Edges: Mapping Severe and Multiple Disadvantage in England’ estimates that each year, over a quarter of a million people in England have contact with at least two out of three of the homelessness, substance use and/or criminal justice systems, and at least 58,000 people have contact with all three. Multiple disadvantage refers to people experiencing three or more challenges concurrently. In the current uncertain climate, the severity and complexity of multiple disadvantage is increasing; and responding at crisis point is harder to resolve someone’s needs and more expensive for the system.

For people experiencing multiple disadvantage, substance use and mental health needs are identified as two of the primary needs. Research suggests that accessing the right support, maintaining support, being discharged from services for missing appointments or for attending appointments while intoxicated, and not being able to access mental health support until having addressed substance use issues are some of the key barriers faced by people experiencing more than one challenge at the same time (“co-occurring conditions” or “dual diagnosis”). [50]

Co-design of services with people with lived experiences helps to challenge assumptions and identify barriers and helps change services and the system to work better for people experiencing multiple disadvantage. Surrey is implementing this in the form of the Changing Futures programme.

Some Surrey residents who experience multiple disadvantage are receiving support from Changing Futures.

The majority (93%) of Changing Futures beneficiaries have experienced mental health issues, and 85% report drug or alcohol use, (figures are based on 1552 national sample). The Bridge the Gap service is funded to support 90 people experiencing severe multiple disadvantage. However, engagement from the wider partnership including service providers and health and social care partners indicates there could be as many as 3,000 people experiencing multiple disadvantage in Surrey, signifying a potential shortfall in provision to meet the current need.

The Bridge the Gap Alliance offers person-centred key-worker support to people experiencing multiple disadvantage, which includes people who use drugs and alcohol. The Alliance is made up of a group of third-sector providers that have partnered to provide a specialist offer of support, and they include Oakleaf, Catalyst, Rentstart, The Hope Hub, Surrey Domestic Abuse Partnership, Guildford Action, Surrey and Borders Partnership, The Richmond fellowship amongst others. [51]

Harm reduction in Surrey

Surrey Public Health commissions needle exchange services via Community Pharmacy. There are two specialised needle exchange services – Guildford Action which is a charity and Woking Exchange run by i-access. In addition, needle exchange and naloxone are also available through other community sites including York Road Project, Catalyst and the Hepatitis C Operational Delivery Network. Some pharmacies have also signed up to provide naloxone in injectable and nasal inhalation form.

There is currently a trial with Guildford Action to provide inhalation kits to reduce the risk of blood borne virus transmission between people who share pipes to take crack cocaine and if successful this will be rolled out to community pharmacies in Surrey.

Nine pharmacies closed in the Surrey Heartlands and Frimley Integrated Care Board areas between the 22nd April and the 13th June 2023, and two additional pharmacies closed within a one-mile of the Surrey area. [52] It is reported by i-access and Luminus that pharmacy closures are likely to negatively impact on service users as individuals may have to travel further and at more expense to access opiate substitute treatment and clean needles. This may result in reduced engagement with these interventions.

Alcohol interventions for adults

Alcohol liaison teams (ALTs) respond to patients presenting acutely to in- or out-patient clinical settings who are assessed as having an alcohol related problem. Their role is to prevent inappropriate admissions and redirect to community alcohol treatment services. Surrey Public Health coordinate with Surrey Heartlands ICS alcohol liaison teams as part of the Combating Drugs Partnership subgroup 4, to reduce alcohol related risks.

Four Surrey trusts currently provide alcohol liaison services, with the biggest being Royal Surrey Hospital which provides services five days a week during working hours. Ashford and St Peters have a smaller team of three alcohol liaison nurses. East Surrey and Frimley Hospital also have smaller alcohol liaison services. Epsom Hospital does not currently provide any alcohol liaison services.

Once the alcohol liaison team have identified inpatients at increased risk from alcohol or alcohol dependency, they refer them to i-access where they are assessed and receive an offer of a treatment pathway appropriate for their needs.

Surrey Public Health and the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner co-commission the High Impact Complex Drinkers (HICD) service. This is provided by VIA who work on a more one-to-one basis with individuals whose drinking is high-risk, and who are not engaged with services. These individuals may be high attenders at A&E or have complex health and/or social care needs.

Surrey Public Health provides funding for training for professionals (from many agencies including NHS, Surrey Police, voluntary organisations) and is producing a making every contact count (MECC)-based alcohol toolkit.

As part of the CDP, Surrey Public Health leads communication campaigns to increase awareness of alcohol-related risks to the wider population. This includes working with partners to promote the main campaigns – alcohol awareness week, dry January, an alcohol-free month – and encourage the uptake of online alcohol tests provided by DrinkCoach.

Prison drug and alcohol services for adults

NHS England commissions drug and alcohol treatment services for people who are in prison. Surrey has five prisons. Drug and alcohol treatment are provided by Forward Trust:

NHS England undertook health needs assessments for residents of Surrey prisons in 2021.

Prevention services for young people

Surrey County Council uses a Healthy Schools approach and commissions materials including education toolkits to support the delivery of PSHE in schools to educate children and young people about substance misuse.

Surrey County Council commissions workers who are integrated into different services such as youth offending, CAMHS and the Surrey Police Child Exploitation and Missing Unit (CEMU).

Catch-22 provide prevention and early intervention work in schools and to Surrey’s youth provision (youth clubs, targeted youth work).

Drugs and alcohol services for young people

The main drug and alcohol service Surrey Public Health commissions for young people is Catch-22 which is a social enterprise for children and young people aged from 11 years up to the age of 25. Within the past year, Surrey Public Health has commissioned Catch-22 to provide dedicated substance use posts based within the Youth Justice Service (YJS) for: young people age <18 years; 18-24 year olds in probation; working directly with CAMHS; and working within the Child Exploitation and Missing Unit (CEMU).

As well as treatment, Catch-22 also engage with schools and deliver training in substance use for all professionals working with young people, including foster carers.

Catch-22 has an additional service called Music to my Ears which engages with young people at risk of becoming involved in the criminal justice system, many of whom use drugs and alcohol.

Amber is a charity which has four supported housing centres in Kent, Surrey, Wiltshire and Devon accepting young people aged 16-30, from across the country. Surrey Public Health commissions two beds for young adults (17-25 years). They tend to be young people who are engaged with Catch-22 and who need assistance in engaging with education, employment or training.

Adults in drug and alcohol treatment – overview

In 2021/22, there were 3,842 adults in drug treatment in Surrey. These comprised 1,228 being treated for opiates, 428 for non-opiates only, 1,657 alcohol only, and 529 non opiate and alcohol.

Young people in drug and alcohol treatment – overview

In 2021/22, 209 young people aged under 18 and 18-24 in young people’s services were in treatment for drugs and alcohol use in Surrey.

Routes into treatment (referral sources)

Routes into adult drug treatment

For adults starting drug treatment in 2021-22 in Surrey, when compared with England, a lower proportion were self-referrals (51% in Surrey vs 57% in England), and criminal justice system referrals (10% vs 17%). A higher proportion were referred by health care or social services – GP (9% vs 4%), hospital/A&E (7% vs 2%), and social services (5% vs 3%). This could indicate that Surrey services are more effective at reaching clients than services in England, such that health and social care services detect and refer patients on appropriately, meaning the need for self-referral or criminal justice referral is lower. Or it could indicate that patients in Surrey do not self-refer at any early enough time and are therefore only referred in for treatment once they have reached a worse condition that required them to seek medical help.

Routes into adult alcohol treatment

For adults starting alcohol treatment in 2021/22 in Surrey, compared with England, a lower proportion were self-referrals (52% in Surrey vs 61% in England), and criminal justice system referrals (4% vs 6%). A higher proportion were referred by health care or social services – GP (16% vs 8%), hospital/A&E (11% vs 7%), and social services (4% vs 3%). This could indicate that Surrey services are more effective at reaching clients than services in England, such that health and social care services detect and refer patients on appropriately, meaning the need for self-referral or criminal justice referral is lower. Health-service referrals are encouraged as formal referrals are trackable, whereas if a person is signposted to self-refer the original referrer will never know if the service ever saw the patient. Or the lower rate of self-referrals in Surrey than England could indicate that patients in Surrey do not self-refer at any early enough time and are therefore only referred in for treatment once they have reached a worse condition that required them to seek medical help.

Routes into young people’s drug and alcohol treatment

In 2021/22, a lower proportion of Surrey under 18s were referred into treatment via education (15%) compared with England (31%) and youth criminal justice system (3% in Surrey and 18% in England). A greater proportion of Surrey than England’s under 18s were referred in by social care (32% vs 25%), self, family and friends (19% vs 11%), and health services (28% vs 14%).

Waiting times for treatment

Waiting times for drug treatment for adults

In 2021/22, 99% of adults waited < 3 weeks for treatment, 1% waited 3-6 weeks, and 0% waited >6 weeks. This is slightly better than England where 98% of adults waited < 3 weeks, 1% waited 3-6 weeks, and 1% waited >6 weeks.

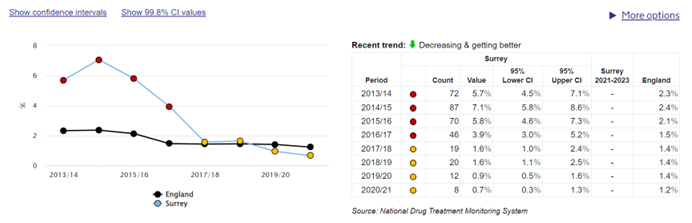

The trend for Surrey has improved over the past decade and continues to improve as per figure 6 below.

Figure 6: proportion waiting more than three weeks for drug treatment [62]

Waiting times for alcohol treatment for adults

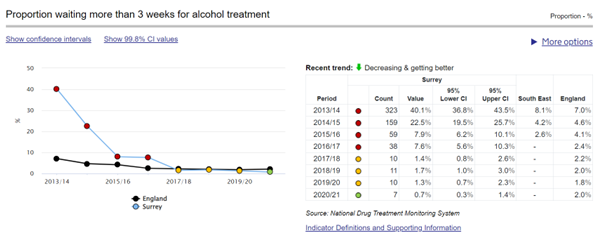

Waiting times for first interventions for Surrey has significantly improved since 2014/15. In 2014/2015, 22.5% of clients waited longer than three weeks to receive treatment. In 2021/22, 99% of all interventions started withing 3 weeks which is similar to England (98%).

Figure 7: Proportion waiting more than 3 weeks for alcohol treatment [62]

Waiting times for drugs and alcohol treatment for children and young adults