People with learning disabilities

People with learning disabilities

Contents

- Glossary

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Local picture

- Health inequalities

- Physical health outcomes

- Respiratory conditions including COVID-19 and vaccination uptake

- Cardiovascular disease

- Hypertension

- Weight management

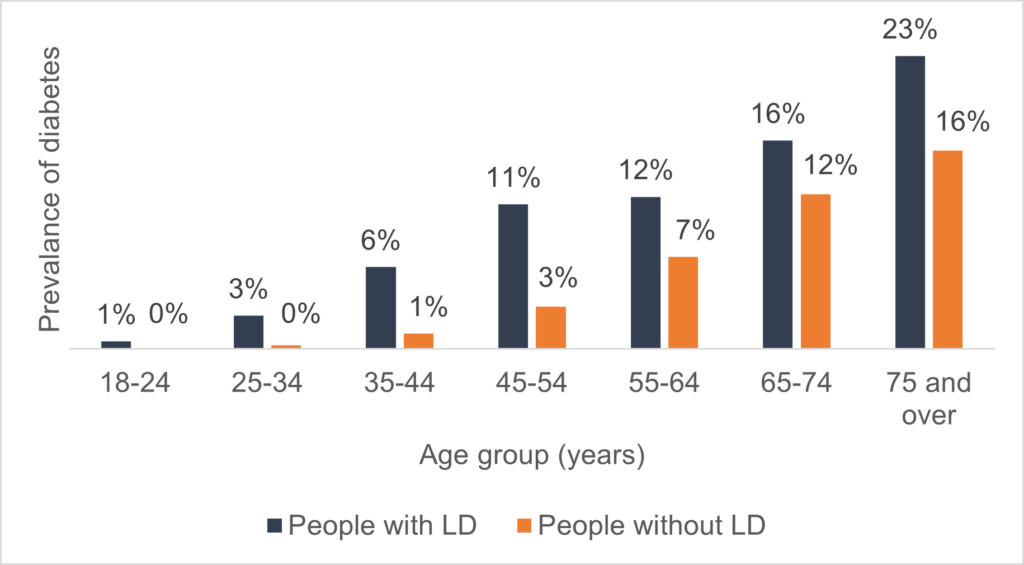

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Cancer and cancer screening

- Physical activity

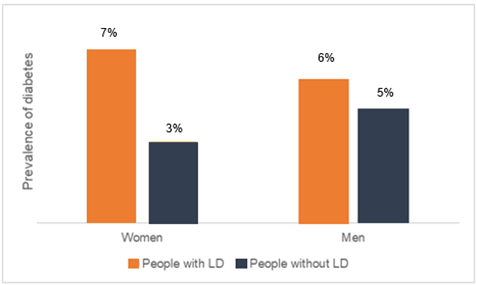

- Gender based inequalities within the learning disabilities population

- Primary Care

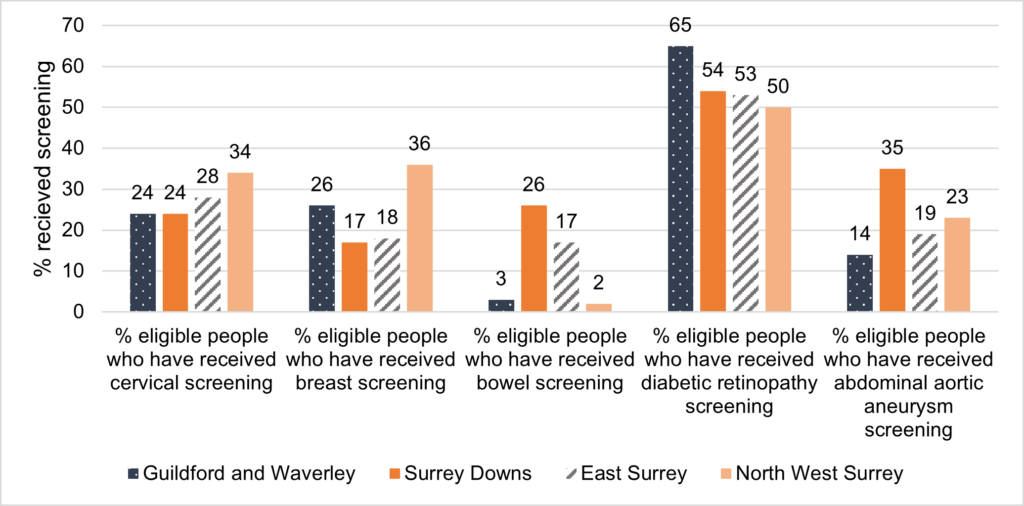

- Variations in physical health between Surrey Heartlands Four ‘Places’

- Dental outcome

- Postural care

- Dementia and learning disabilities

- People with learning disabilities and ageing

- Sensory impairment

- Podiatry

- Sex, sexual health, sexual awareness and sexual expression

- Pregnancy care and outcomes

- Access to health services

- Access to primary care

- Access to acute healthcare

- Hospital learning disability team

- Specialist Health Care support

- Mental health and outcomes, including inpatient admissions

- STOMP and STAMP (STopping Over Medication of People with a learning disability, autism or both with Psychotropic Medicines)

- Inpatient Use

- Wider determinants

- Poverty and Health

- Accommodation

- Employment

- Hate and mate crime

- Domestic Abuse

- Crime, concerning behaviour

- Community voice

- Evidence base, what works

- Summary of Recommendations

- Appendices

- Chapter Contacts

- References

Glossary

ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

AHC Annual Health Check

ASD / ASC Autistic Spectrum Disorder / Autistic Spectrum Condition

BMI Body Mass Index

CASSR Councils with Adult Social Services Responsibilities

CETR Care, Education and Treatment Review

CIPFA Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy

CQC Care Quality Commission

CTR Care and Treatment Review

CTPLD Community Team for People with Learning Disabilities

CVD Cardiovascular Disease

DNACPR Do not Attempt Resuscitation

EHCP Education, Health and Care Plan

GORD Gastric oesophageal reflux disease

ICP Integrated Care Partnership

ICS Integrated Care System

IHD Ischaemic Heart Disease

JSNA Joint Strategic Needs Assessment

LeDeR Learning from Lives and Deaths of People with a Learning Disability

NHS National Health Service

NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

PANSI Projecting Adult Needs and Service Information

PCC Primary Client Category

PLD People with Learning Disabilities

POPPI Projecting Older People Population Information

PSR Primary Support Reason

SCC Surrey County Council

SCIE Social Care Institute for Excellence

STOMP Stopping over medication of people with a learning disability, autism or both

STAMP Supporting Treatment and Appropriate Medication in Paediatrics

TIA Transient Ischaemic Attack

Executive Summary

The national policy direction for people with a learning disability (including those with autism) remains one of a human rights based approach and one where adults, children, and young people with a learning disability, and autistic adults, children and young people should be equal citizens in their communities as referenced in the ‘Building the Right Support Action plan 2022’ (BTRS plan)

This Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) outlines what we know about the lives of people with learning disabilities of all ages in Surrey, their health outcomes and access including the experience of Covid, social care needs and provision, their living circumstances, education and employment and how much of a voice they have in their lives, services they use and their communities.

It also outlines where we need to know more about the impact of the cost of living crisis, access to community health, police services and support in prison for people with learning disabilities. In doing so, it challenges Surrey to ensure that the vision of ‘no one is left behind’ becomes a reality for this highly diverse group within our communities.

The JSNA makes fifty recommendations, testament to the need to better understand the experiences in Surrey of people with learning disabilities. These are threaded throughout the JSNA and are brought together in one section towards the end of the JSNA. They come under the following themes:

- Legislative / Policy Framework

- Primary care, all-age learning disability registers

- Learning disability population projections

- Number of adults with a learning disability open to Social Care

- Safeguarding

- Prevalence of behaviour risk factors

- Physical health outcomes

- Gender based inequalities within the learning disabilities population

- Primary Care

- Variations in physical health between Surrey Heartlands Four ‘Places’

- Dental outcome

- Postural care

- Dementia and learning disabilities

- People with learning disabilities and ageing

- Sensory Impairment

- Podiatry

- Sex, sexual health, sexual awareness and sexual expression

- Pregnancy care and outcomes

- Access to health services

- Mental health and outcomes, including inpatient admissions

- Integrated Intensive Support Service

- LAEP meeting and Care (education) and treatment reviews

- Future considerations for proposed Mental Health Act changes

- Poverty and Health

- Employment

- Domestic Abuse

- Crime, concerning behaviour

- Adult Social Care Survey England – 2020/21

Introduction

This JSNA outlines what we know about the lives of people with learning disabilities of all ages in Surrey, their health outcomes and access including the experience of Covid, social care needs and provision, their living circumstances, education and employment and how much of a voice they have in their lives, services they use and their communities.

It also outlines areas where we need to know more, for example about the impact of the cost of living crisis, access to community health, police services and support in prison for people with learning disabilities. In doing so, it challenges Surrey to ensure that the vision of ‘no one is left behind’ becomes a reality for this highly diverse group within our communities.

The JSNA aims to cover all ages as far as possible, with reference to further detail for children and young people contained within the Children and Young People with Additional Needs and Disabilities Joint Strategic Needs Assessment.

It seeks to look at support in the round and identify how people’s experiences can be better understood, the hard and soft intelligence, quantitative and qualitative data.

The county of Surrey falls into the boundaries of two integrated care systems – Surrey Heartlands (the predominant part) and Frimley. This JSNA attempts to cover both Surrey Heartlands and Frimley and specify where this has not been possible due to a lack of pertinent data.

Surrey Context

The Community Vision for Surrey states that by 2030, Surrey will

‘…be a uniquely special place where everyone has a great start to life, people live healthy and fulfilling lives, are enabled to achieve their full potential and contribute to their community and no one is left behind.’

The ambitions for people that the Strategy set out are as follows:

- Children and young people are safe and feel safe and confident.

- Everyone benefits from education, skills and employment opportunities that help them succeed in life.

- Everyone lives healthy, active and fulfilling lives, and makes good choices about their wellbeing.

- Everyone gets the health and social care support and information they need at the right time and place.

- Communities are welcoming and supportive, especially of those most in need, and people feel able to contribute to community life.

The Strategy also set out ambitions for the place:

‘…our county’s economy to be strong, vibrant and successful and Surrey to be a great place to live, work and learn. A place that capitalises on its location and natural assets, and where communities feel, and people can support each other.’

In 2022 the refreshed Health and Wellbeing Strategy set out Surrey’s priorities and captures the revised outcomes. It identifies specific groups of people who experience health inequalities that have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic and outlines how we need to collaborate so we can better meet their needs.

The Integrated Care System will focus on delivering these outcomes within our priority populations – communities of identity and geography which are often overlooked and currently most at risk of experiencing poor health outcomes, as identified by the COVID Community Impact Assessment and Rapid Needs Assessments.

This includes people who experience the poorest health outcomes:

- Children with additional needs and disabilities

- Adults with learning disabilities and/or autism

Surrey will remain focused on three interconnected priorities – supporting people to lead physically healthy lives / to have good mental health and emotional wellbeing and creating the contexts in which individuals and communities can reach their potential, with a clearer intent on addressing the wider determinants of health. These priorities adopt both primary prevention (stopping ill health in the first instance) and secondary/tertiary prevention (making sure things don’t get any worse) approach, and focus on providing the right physical, psychological, social and economic contexts for communities that experience the poorest health outcomes to begin to thrive.

The Health and Well Being Board strategic focus will continue to evolve, reflecting the latest data, evidence, and insights, including that presented in the different chapters of the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) as they are updated in accordance with the rolling programme.

Scope

What is a learning disability

Learning disability’ is an umbrella term used to describe people who have “a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn new skills (impaired intelligence); a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning) and; a disability that started before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development”.

The term ‘intellectual disability’ is also used both within research and within the International Classification of Disease coding system where the description also includes impairment of cognitive, motor and social abilities. The coding system defines learning disability by severity using IQ as a guide; a person with an IQ less than 70 is considered to have a learning disability. Alongside an IQ of less than 70, the other two core criteria indicating a learning disability are significant impairment of social or adaptive functioning and onset in childhood. These are used as both diagnostic criteria and as a diagnosis code within the NHS.

For the purposes of this JSNA ‘learning disability’ is used as a definition except where children’s Special Educational Needs coded data is referenced as this utilises the terms ‘moderate learning difficulty’, ‘severe learning difficulty’ and ‘profound multiple learning difficulty’, which relate to general impairments in learning of different severity. These can be interchangeable with the term ‘learning disability’ and the groups of mild, moderate, severe and profound learning disabilities.

People with learning disabilities are not one homogenous group. They can have associated conditions, some of the most common of which are Down Syndrome, Autism, Williams Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome and Cerebral Palsy. See Appendix 1 for further detail. [1] [2] [3]

What a learning disability is not

Mencap states that ‘a learning disability is different from a learning difficulty as a learning difficulty does not affect general intellect’. Learning difficulties can include dyslexia, dyspraxia, and dyscalculia. These learning difficulties can co-occur alongside a learning disability. A Learning Difficulty is a type of Special Education Need (SEN) which affects areas of learning, such as reading, writing, spelling and mathematics.

What causes a learning disability [4]

We do not always know why a person has a learning disability [5]. Sometimes it is because a person’s brain development is affected, either before they are born, during their birth or in early childhood. Possible causes include:

- the mother becoming ill in pregnancy

- problems during the birth that stop enough oxygen getting to the brain

- the unborn baby having some genes passed on from its parents that make having a learning disability more likely

- illness, such as meningitis, or injury in early childhood

There are specific health conditions where a learning disability is more likely such as Down’s syndrome, where everyone is likely to have some level of learning disability, many autistic people, and people with cerebral palsy.

Mild Learning Disability is usually caused by a combination of restricted learning and social opportunities plus a high rate of low to average intellectual ability and learning disability in close relatives.

Moderate-to-profound Learning Disability usually has a specific biological cause.

Key policy drivers for changes or improvements relevant to learning disabilities

There are several key policy and guidance drivers for change and improvement relevant to people with learning disabilities.

The ‘Building the Right Support Action plan 2022’ published July 2022, is an action plan to strengthen community support for people with a learning disability and autistic people and to reduce reliance on mental health inpatient care.

The driver for the action plan is ‘adults, children, and young people with a learning disability, and autistic adults, children and young people should be equal citizens in their communities’.

The action plan brings together, in one place, commitments across systems to reduce reliance on inpatient care in mental health hospitals for children, young people and adults with a learning disability and for autistic children, young people and adults by building the right support in the community.

The key areas of focus set out in this action plan are:

- ensuring that people with a learning disability and autistic people of all ages experience high-quality, timely support that respects individual needs and wishes, and upholds human rights

- understanding that every citizen has the right to live an ordinary, self-directed life in their community

- keeping each person at the centre of our ambitions and ensuring that we consider a person’s whole life journey

- collaborating across systems to put in place the support that prevents crisis and avoids admission

- ensuring that, when someone would benefit from admission to a mental health hospital, they receive therapeutic, high-quality care and remain in hospital for the shortest time possible

- making sure that the people with a learning disability and autistic people who are in mental health hospitals right now are safe, and that they are receiving the care and treatment that is right for them

- working together to ensure that any barriers to an individual leaving a mental health hospital, when they are ready to do so, are removed

The action plan is arranged into 6 chapters:

- Keeping people safe and ensuring high-quality health and social care

- Making it easier to leave hospital

- Living an ordinary life in the community

- A good start to life

- Working with changes to the system

- National and local accountability to deliver

The immediate and future impacts of this action plan are included within this chapter.

The Down Syndrome Act 2022 became law in April 2022 with an aim of improving access to services and to improve the quality of life for people with Down’s syndrome. It aims to ensure that health, social care, education and other local authority services such as housing take account of the specific needs of people with Down’s syndrome when commissioning or providing services.

The Act requires the Secretary of State to publish guidance for relevant authorities (for example, NHS hospitals or local councils) on the steps it would be appropriate for those authorities to take to meet the needs of people with Down’s syndrome when carrying out some of their most important functions. Once the guidance is published these authorities are legally required to take the guidance into account when providing certain core services.

A call for evidence is currently underway to inform the guidance.

Recommendation: Following the publication of the evidence we will review whether the detail of Down Syndrome Act is already in place and consider the impact of the Act and subsequent guidance both on this community and the wider community of people with learning disabilities.

The NHS Long Term Plan (2019), Chapter Three, sets the NHS’s priorities for care quality and outcomes improvement for the decade from 2019 which includes people with learning disabilities.

The priorities are:

Action taken to tackle the causes of morbidity and preventable deaths in people with a learning disability and for autistic people by:

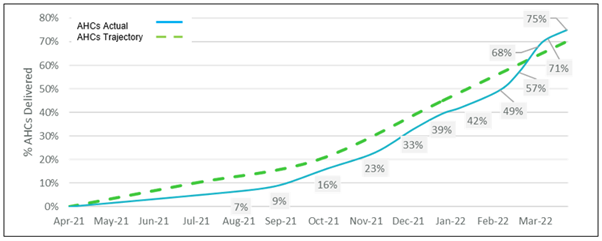

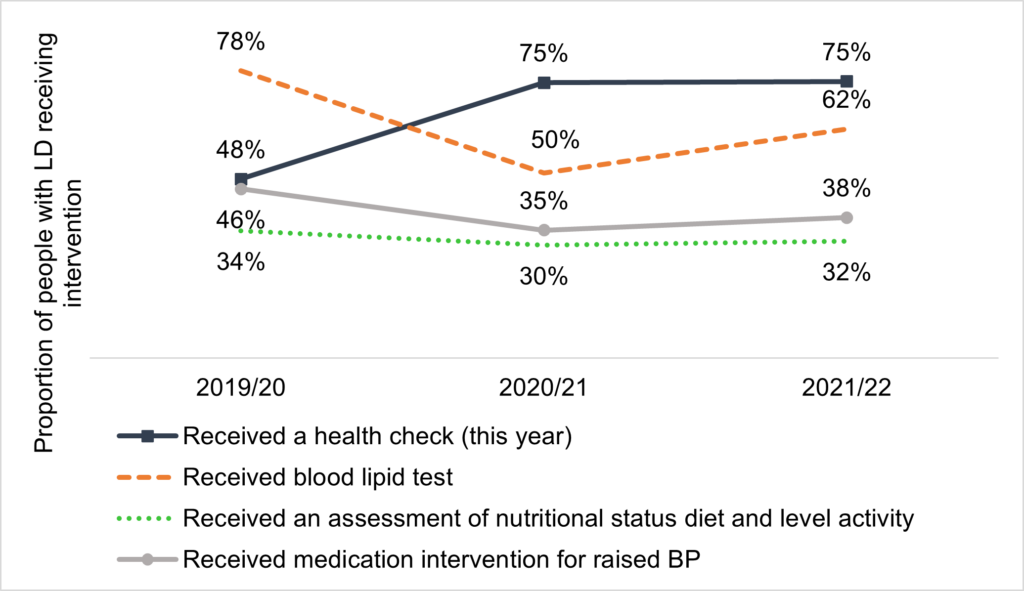

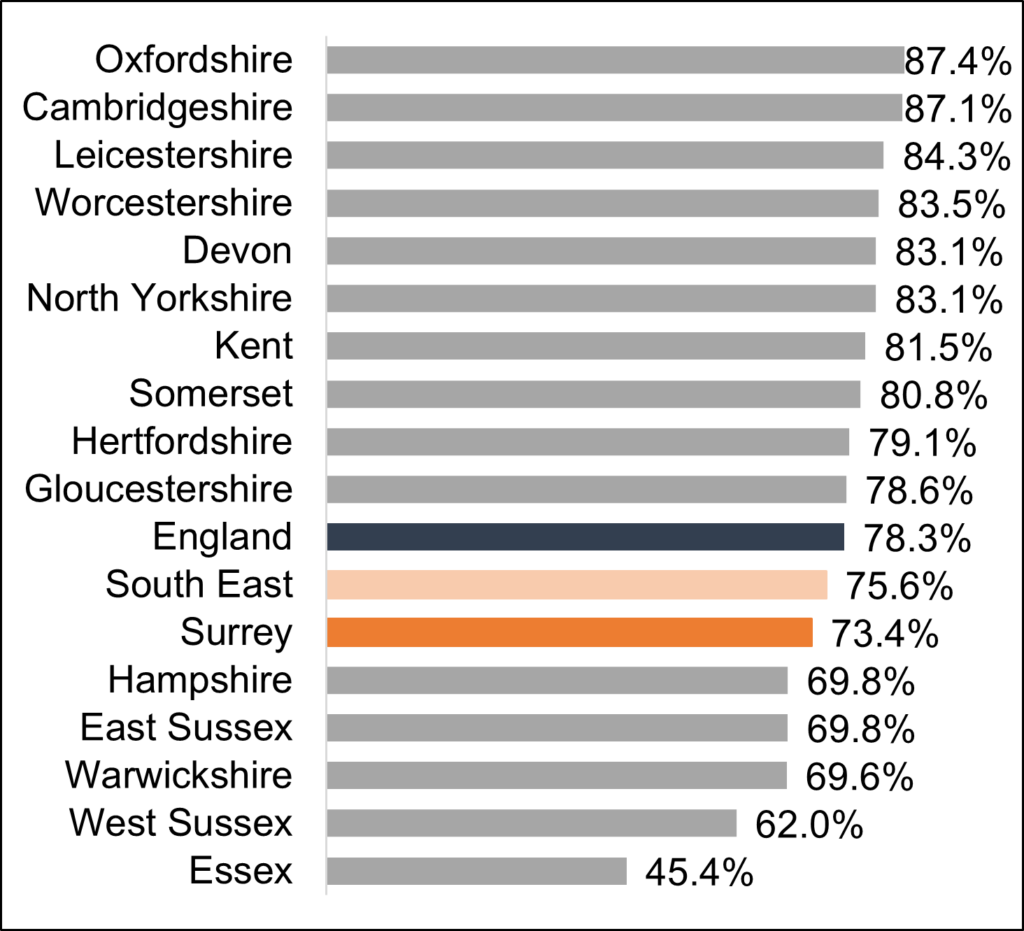

- Increasing uptake of the existing annual health check (‘AHC’) in primary care for people aged over 14 years with a learning disability to at least 75% of those eligible.

- Expand the Stopping over medication of people with a learning disability autism or both and Supporting Treatment and Appropriate Medication in Paediatrics (STOMP-STAMP) programmes to stop the overmedication of people with a learning disability.

- Continue to fund the Learning Disabilities Mortality Review Programme (LeDeR), the first national programme aiming to make improvements to the lives of people with learning disabilities.

The whole NHS will improve its understanding of the needs of people with learning disabilities and autism, and work together to improve their health and wellbeing

- NHS staff will receive information and training on supporting people with a learning disability and/ or autism (this has since developed into the Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training)

- Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) and integrated care systems (ICSs) will be expected to make sure all local healthcare providers are making reasonable adjustments to support people with a learning disability or autism.

- National learning disability improvement standards will be implemented and will apply to all services funded by the NHS.

- By 2023/24, a ‘digital flag’ in the patient record will ensure staff know a patient has a learning disability or autism

- Work with the Department for Education and local authorities to improve their awareness of, and support for, children and young people with learning disabilities, autism or both

- Work with partners to bring hearing, sight and dental checks to children and young people with a learning disability, autism or both in special residential schools

Children and young people with suspected autism wait too long before being provided with a diagnostic assessment

- Autism diagnosis will be included alongside work with children and young people’s mental health services to test and implement the most effective ways to reduce waiting times for specialist services to attempt to achieve timely diagnostic assessments in line with best practice guidelines.

- Together with local authority children’s social care and education services as well as expert charities, we will jointly develop packages to support children with autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and their families, throughout the diagnostic process.

- By 2023/24 children and young people with a learning disability, autism or both with the most complex needs will have a designated keyworker, implementing the recommendation made by Dame Christine Lenehan.

Children, young people and adults with a learning disability, autism or both, with the most complex needs, have the same rights to live fulfilling lives

- By March 2023/24, inpatient provision will have reduced to less than half of 2015 levels (on a like for like basis and taking into account population growth).

- For everyone million adults, there will be no more than 30 people with a learning disability and/or autism cared for in an inpatient unit.

- For children and young people, no more than 12 to 15 children with a learning disability, autism, or both per million, will be cared for in an inpatient facility.

- To move more care to the community, we will support local systems to take greater control over how budgets are managed. Drawing on learning from the New Care Models in tertiary mental health services, local providers will be able to take control of budgets to reduce avoidable admissions, enable shorter lengths of stay and end out of area placements.

- Where possible, people with a learning disability, autism or both will be enabled to have a personal health budget (PHBs).

Increased investment in intensive, crisis and forensic community support will also enable more people to receive personalised care in the community, closer to home, and reduce preventable admissions to inpatient services

Every local health system will be expected to use some of this growing community health services investment to have a seven-day specialist multidisciplinary service and crisis care. We will continue to work with partners to develop specialist community teams for children and young people, such as the Ealing Model, which has evidenced that an intensive support approach prevents children being admitted into institutional care.

Focus on improving the quality of inpatient care across the NHS and independent sector. By 2023/24, all care commissioned by the NHS will need to meet the Learning Disability Improvement Standards

- Work with the CQC to implement recommendations on restricting the use of seclusion, long-term segregation and restraint for all patients in inpatient settings, particularly for children and young people.

- Closely monitor and bring down the length of time people stay in inpatient care settings and support earlier transfers of care from inpatient settings.

- All areas of the country will implement and be monitored against a ‘12-point discharge plan’ to ensure discharges are timely and effective.

- Review and look to strengthen the existing Care, Education and Treatment Review (CETR) and Care and Treatment Review (CTR) policies, in partnership with people with a learning disability, autism or both, families and clinicians to assess their effectiveness in preventing and supporting discharge planning. This update was released in January 2023.

The Surrey Heartlands geography has a three-year delivery plan 2021/22 to2023/24 which describes their commitments against the long-term plan and is aligned with the Frimley plan to ensure Surrey wide coverage. The county of Surrey falls into the boundaries of two systems – Surrey Heartlands (the larger part) and Frimley. The Surrey Heartlands delivery plan includes specific projects and actions that were committed to against the long-term plan including AHC delivery and reducing reliance on inpatient beds. Much of the plan is referenced within this JSNA.

Recommendation: Use the outputs from all of the reports of The learning disability improvement standards for NHS trusts in strategic discussions to share good practice and reduce unwarranted variation across Surrey.

Recommendation: Joint work across health and social care system leaders, including leaders at ‘place’, to ensure that the full benefits of the Fuller Stocktake are fully realised for people with a learning disability.

Local picture

Population distribution

Primary care, all-age learning disability registers

Learning disability registers are lists of children, young people and adults who have a learning disability. The register is used by doctors to ensure that people with a learning disability can get the right help and support. Young people and adults over 14 years can have a free AHC (see the access section for uptake of health checks).

To get on the register the GP must enter an appropriate recognised learning disability code onto the patient’s records (usually simply “Learning Disability” but there are variations that will also get picked up). If the patient has the correct code in their notes they are automatically on the Learning Disability register – the patient record system creates the register directly from the codes.

There is some concern raised between system leaders within children’s services that the use of a diagnostic process does not identify everyone with a learning disability and that there is a resulting impact upon people’s access to services including a lack of clarity about the terminology used in children’s services, specifically ‘global developmental delay’.

Recommendation: Surrey all-age system leaders need to consider what diagnostic processes are in place and, depending upon the findings, consider if access to services in the future will not be diagnostic dependent.

Recommendation: Surrey all-age system leaders need to consider how best to provide clarity regarding terminology and ensure that necessary differences does lead to poor access or the robustness of intelligence.

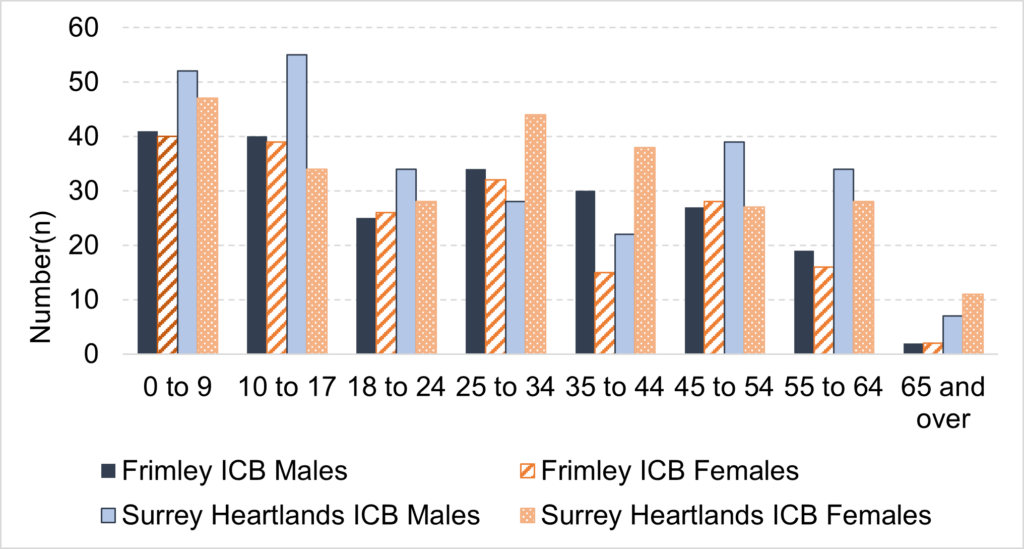

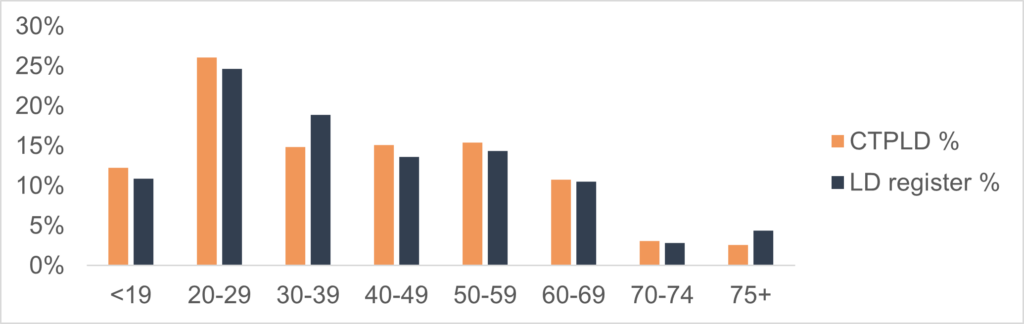

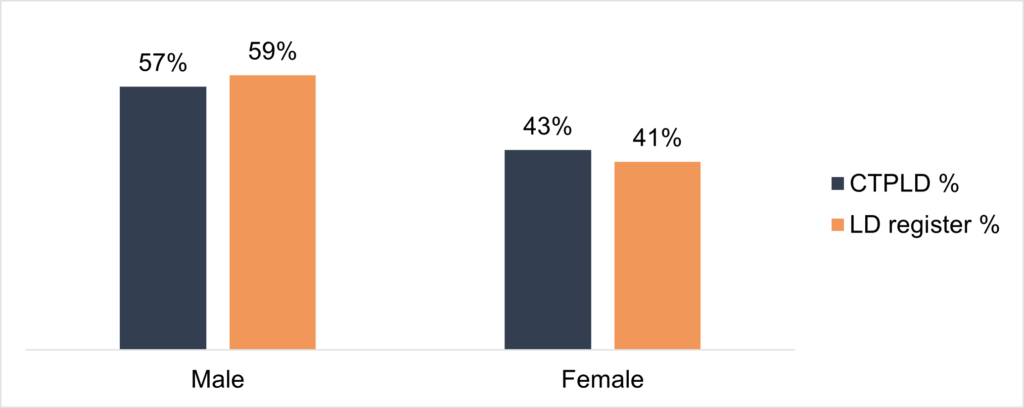

Tables 1 and 2 show the number of children, young people and adults on the learning disability register in Surrey Heartlands and Frimley ICBs respectively. The proportion of males on the disability register is higher than females for both ICBs at 59.7% for Surrey Heartlands and 58.1% for Frimley (higher numbers for males are typical nationally both currently and in recent history).

Table 1: Surrey Heartlands ICB population with a learning disability on the Learning Disability Register, 2020/21

| Surrey Heartlands ICB | Number Aged <18 | Number Aged 18-24 | Number Aged 25-64 | Number Aged 65-74 | Number Aged 75+ | Number All Ages |

% Aged <18 | % Aged 18-24 | % Aged 25-64 | % Aged 65-74 | % Aged 75+ |

| Persons | 772 | 641 | 2,630 | 313 | 140 | 4,496 | 17.2 | 14.3 | 58.5 | 7.0 | 3.1 |

| Male | 491 | 434 | 1,501 | 177 | 81 | 2,684 | 10.9 | 9.7 | 33.4 | 3.9 | 1.8 |

| Female | 281 | 207 | 1,129 | 136 | 59 | 1,812 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 25.1 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

Source: NHS Digital, Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities, 2020/21

Table 2: Frimley ICB population with a learning disability on the Learning Disability Register, 2020/21

| Frimley ICB | Number Aged <18 | Number Aged 18-24 | Number Aged 25-64 | Number Aged 65-74 | Number Aged 75+ | Number All Ages |

% Aged <18 | % Aged 18-24 | % Aged 25-64 | % Aged 65-74 | % Aged 75+ |

| Persons | 525 | 456 | 1,700 | 169 | 62 | 2,912 | 18.0 | 15.7 | 58.4 | 5.8 | 2.1 |

| Male | 315 | 262 | 983 | 101 | 32 | 1,693 | 10.8 | 9.0 | 33.8 | 3.5 | 1.1 |

| Female | 210 | 194 | 717 | 68 | 30 | 1,219 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 24.6 | 2.3 | 1.0 |

Source: NHS Digital, Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities, 2020/21

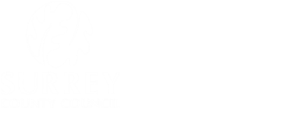

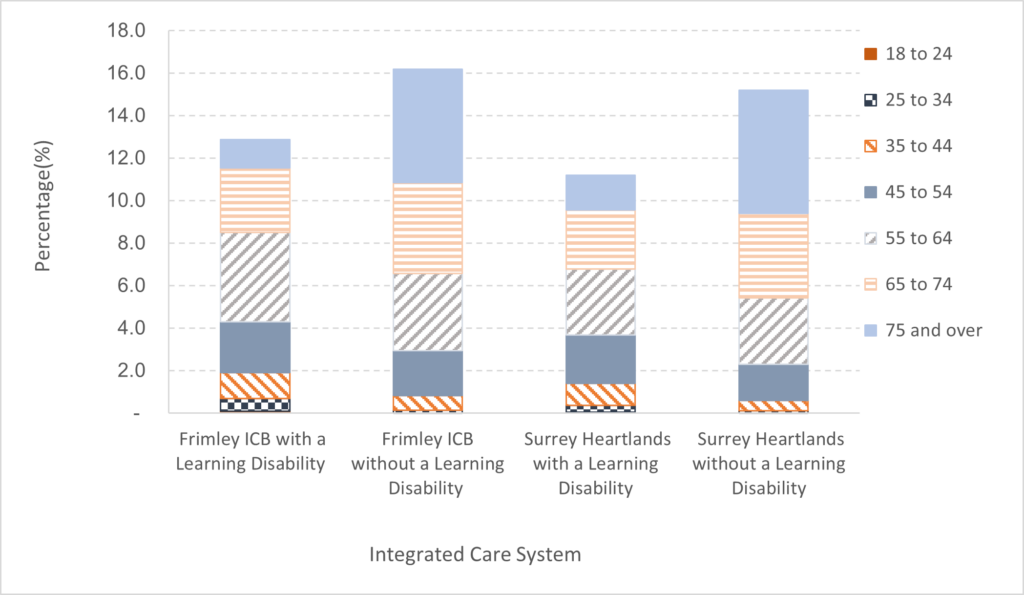

Figure 1: Frimley ICB population pyramid 2020/21

Source: NHS Digital, Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities, 2020/21

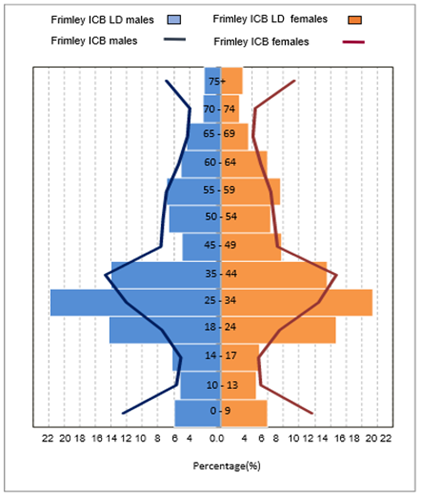

Figure 2: Surrey Heartlands ICB population pyramid 2020/21

Source: NHS Digital, Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities, 2020/21

Public Health England ‘Learning Disabilities Observatory People with learning disabilities in England 2015: Main report’ indicated only 23% of adults with learning disabilities in England are identified as such on GP registers and considered this the most comprehensive identification source within health or social services in England. It is estimated that in 2023 approximately 22,000 adults in Surrey will have a learning disability, with only a proportion of this group known to health and social services. Applying the 23% to the overall prevalence rate, we should have 5060 people on the GP register (which is broadly the case) [6].

However, the remaining 77% are often referred to as the ‘hidden majority’ of adults with learning disabilities who typically remain invisible in data collections and in this case, not on a register which would entitle them to an annual health check [7].

Recommendation: To increase the number of people of all ages with a learning disability on the GP Register, paying particular attention to those from minority groups. There is no available breakdown by ethnic group. This is a symptom of a broader lack of routine ethnic monitoring in General Practice that needs to be addressed.

Learning disability population projections

Predictions are based on national prevalence estimates, using an adjusted model to predict population, which takes into account local ethnicity and mortality rates. They should be viewed in the context of advances in medical science which lead a greater number of people having a longer life expectancy from birth.

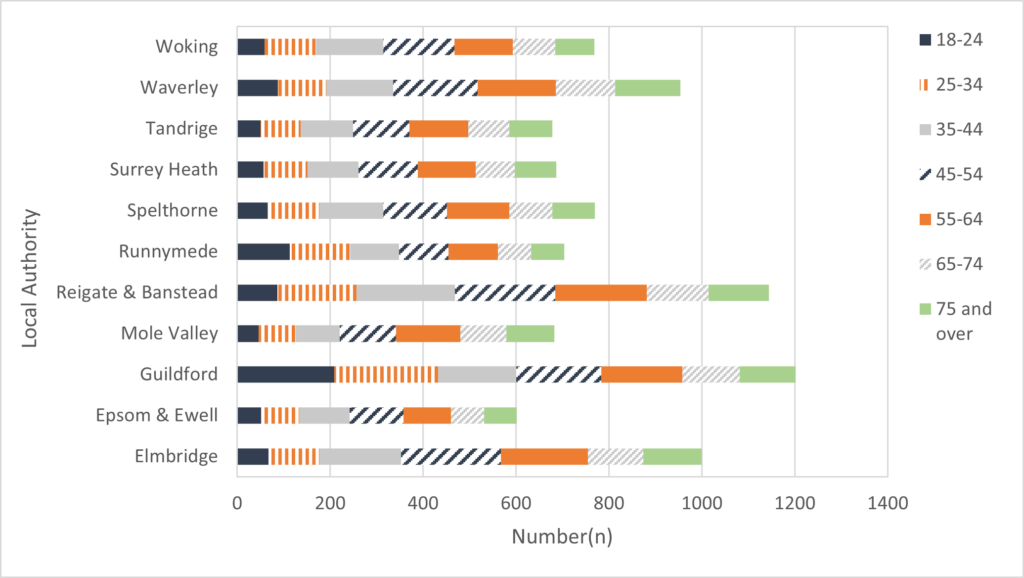

The estimated number of adults in Surrey aged 18+ with a learning disability is expected to increase by around 4.5% over time from 21,980 in 2023 to 22,971 in 2040 (Table 3). This is comparable with the estimated increase in the general population aged 18 years and over of 4.4% over the same time period.

Table 3: People in Surrey aged 18+ predicted to have a learning disability by age group, projected to 2040*

| Age Group | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| 18 to 24 | 2,342 | 2,383 | 2,655 | 2,677 | 2,493 |

| 25 to 34 | 3,200 | 3,142 | 3,010 | 3,125 | 3,374 |

| 35 to 44 | 3,858 | 3,784 | 3,647 | 3,521 | 3,385 |

| 45 to 54 | 3,988 | 4,000 | 3,939 | 3,853 | 3,727 |

| 55 to 64 | 3,616 | 3,665 | 3,629 | 3,567 | 3,534 |

| 65 to 74 | 2,467 | 2,500 | 2,825 | 3,049 | 3,037 |

| 75 to 84 | 1,760 | 1,843 | 1,909 | 1,951 | 2,249 |

| 85 and over | 750 | 778 | 893 | 1,100 | 1,172 |

| Total | 21,980 | 22,096 | 22,507 | 22,843 | 22,969 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI September 2022 (Data uses POPPI and PANSI national prevalence model applied to the ONS population projections)

The projected increase is lower than nationally, which is estimated as around 8.9% and regionally which is around 8.1% over time from 21,980 in 2023 to 22,971 in 2040 (Table 4).

Table 4: People in Surrey aged 18+ predicted to have a learning disability in England, South East region, Surrey, and local authorities, projected to 2040*

| Local Authority | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| England | 1,065,608 | 1,077,318 | 1,110,872 | 1,141,293 | 1,160,822 |

| South East | 172,533 | 174,341 | 179,540 | 183,938 | 186,564 |

| Surrey | 21,980 | 22,096 | 22,507 | 22,843 | 22,969 |

| Elmbridge | 2,415 | 2,425 | 2,468 | 2,497 | 2,514 |

| Epsom & Ewell | 1,457 | 1,462 | 1,497 | 1,524 | 1,535 |

| Guildford | 2,868 | 2,875 | 2,924 | 2,944 | 2,932 |

| Mole Valley | 1,615 | 1,616 | 1,640 | 1,658 | 1,672 |

| Reigate & Banstead | 2,751 | 2,784 | 2,875 | 2,947 | 3,006 |

| Runnymede | 1,714 | 1,729 | 1,771 | 1,795 | 1,798 |

| Spelthorne | 1,828 | 1,835 | 1,865 | 1,893 | 1,906 |

| Surrey Heath | 1,630 | 1,627 | 1,647 | 1,656 | 1,662 |

| Tandridge | 1,625 | 1,637 | 1,678 | 1,712 | 1,740 |

| Waverley | 2,275 | 2,291 | 2,327 | 2,359 | 2,370 |

| Woking | 1,813 | 1,821 | 1,829 | 1,839 | 1,844 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI September 2022

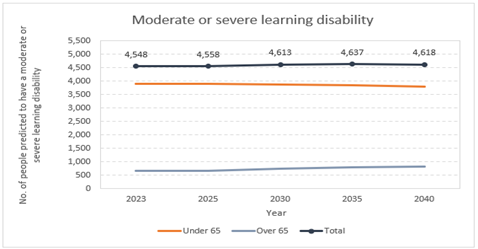

Among the estimated number of adults in Surrey aged 18+ with a learning disability, the number with a moderate or severe learning disability, estimated as 4,546 in 2023, is projected to increase to 4,637 by 2040 (figure 3).

Figure 3: Estimated number of adults to have a moderate to severe learning disability in Surrey, projected to 2040

Source: POPPI and PANSI September 2022

Down’s Syndrome

Down’s syndrome and the learning disability register

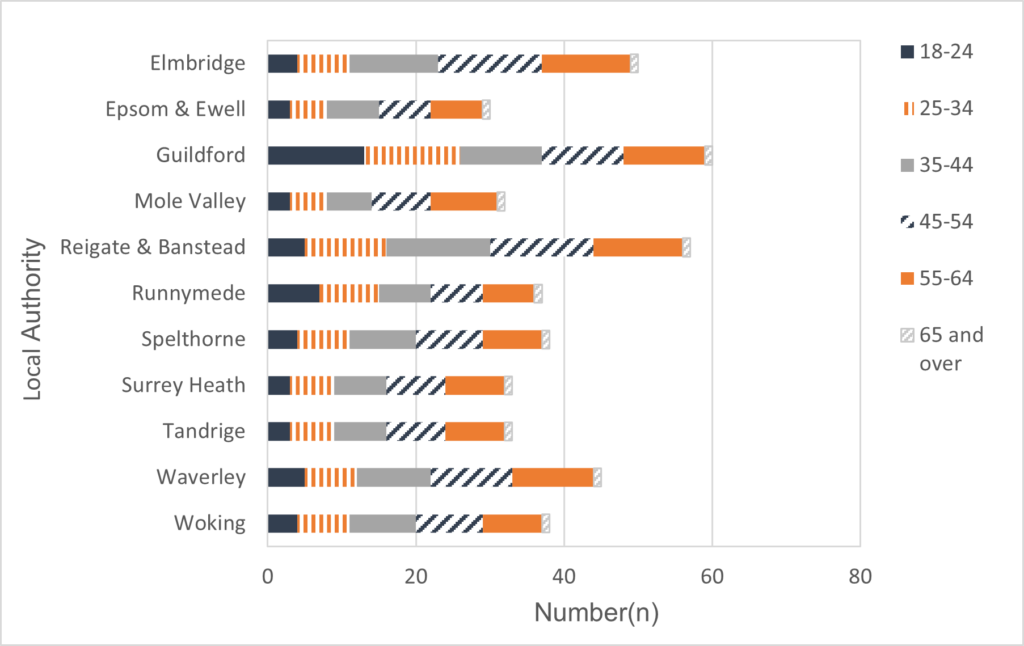

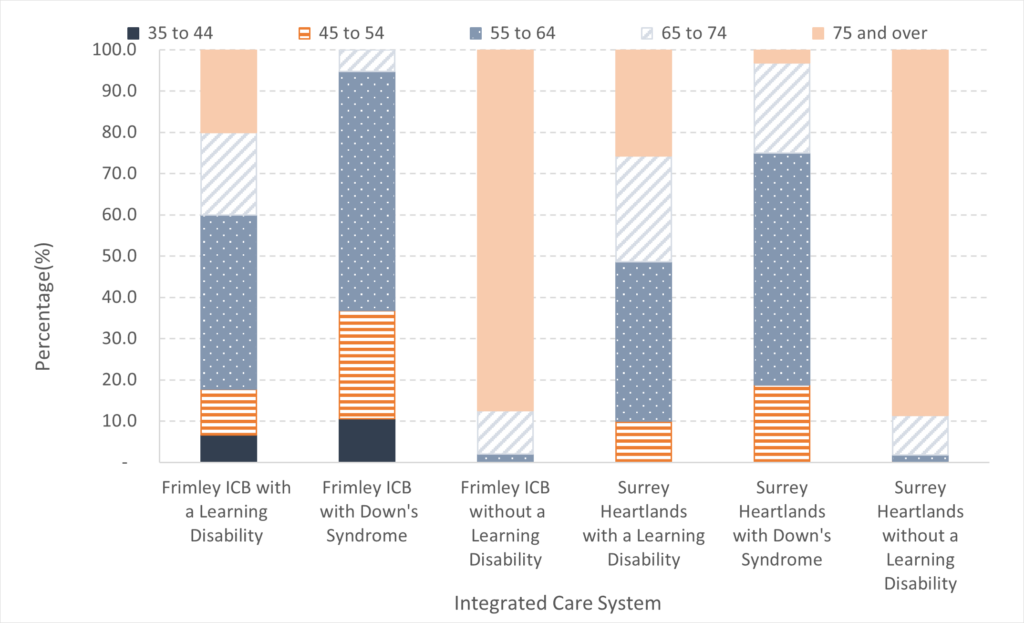

There are 945 children, young people and adults registered on a GP disability register with a diagnosis of Downs syndrome. Approximately 36.8% are children and young people aged under 18 years, 60.7% are adults of working age (18 to 64 years) and 2.3% are 65 years and over. There are slightly more males (51.9%) than females (48.1%). (Figure 4).

(Data regarding the incidence of Downs Syndrome is available through the work done in preparation for the Down’s Syndrome Act. Data regarding other learning disabilities is not available.)

Figure 4: Population breakdown for people with Down’s Syndrome by gender and age groups, by ICB

Source: NHS Digital, Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities, 2020/21

Down’s syndrome projections

Using an adjusted model to predict population which takes into account local ethnicity and mortality rates, it is estimated that in 2023 approximately 446 adults (aged 18+) in Surrey will have Down’s Syndrome.

Table 5: Estimated number of adults with Down’s Syndrome by age group living in Surrey, projected to 2040

| Age Group | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| 18 to 24 | 54 | 55 | 62 | 63 | 58 |

| 25 to 34 | 80 | 79 | 76 | 78 | 85 |

| 35 to 44 | 98 | 96 | 92 | 89 | 85 |

| 45 to 54 | 106 | 106 | 104 | 101 | 97 |

| 55 to 64 | 99 | 101 | 100 | 98 | 97 |

| 65 and over | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 11 |

| Total | 446 | 446 | 444 | 439 | 433 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI, October 2022

This number is expected to decrease by 2.9% to 433 in 2040 (the estimates for the all individual local authorities in Surrey 2023 are predicted to decrease or remain the same by 2040). This decrease is different to what is predicted nationally where a 1.8% increase is estimated.

Table 6: Estimated number of adults with Down’s Syndrome, in England, South East region, Surrey and local authorities, projected to 2040*

| Local Authority | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| England | 21,808 | 21,902 | 22,068 | 22,189 | 22,292 |

| South East | 3,478 | 3,488 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,493 |

| Surrey | 446 | 446 | 443 | 438 | 433 |

| Elmbridge | 49 | 49 | 48 | 47 | 46 |

| Epsom & Ewell | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Guildford | 60 | 60 | 60 | 59 | 58 |

| Mole Valley | 31 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 29 |

| Reigate & Banstead | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 |

| Runnymede | 36 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 36 |

| Spelthorne | 38 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 37 |

| Surrey Heath | 33 | 33 | 32 | 31 | 31 |

| Tandridge | 33 | 33 | 33 | 32 | 32 |

| Waverley | 44 | 44 | 43 | 43 | 42 |

| Woking | 38 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 36 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI, December 2022

Figure 5: Number of people aged 18+ predicted to have Down syndrome by age group, living in Surrey, 2023

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI, December 2022

Autism

The Autistica website suggests that around 40% of autistic people have a learning disability, compared with just 1% of people without autism. Around 1 in 10 people with a learning disability are autistic so the two significantly co-occur [8].

Surrey has an All-Age Autism Strategy. A separate chapter of the overall JSNA looking at neurodivergent people including autistic people is being produced.

The Surrey All Age Autism Strategy indicates that it is common for autistic people to have other neurodevelopmental conditions, including learning disabilities (affecting between 15% and 30% of autistic people). Delays in language development are common in autism, and up to 30% of autistic people are non-speaking (completely, temporarily, or in certain contexts).

Using an adjusted model to predict population which takes into account local ethnicity and mortality rates, it is estimated that in 2023 approximately 9,183 adults (aged 18+) in Surrey are Autistic. The estimated number of Autistic people in Surrey aged 18+ is expected to increase by 5.2% from 2023 to 2040 (9,661).

Table 7: Estimated number of autistic people by age group living in Surrey, projected to 2040

| Age Group | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| 18 to 24 | 889 | 907 | 1014 | 1024 | 958 |

| 25 to 34 | 1,297 | 1281 | 1235 | 1286 | 1389 |

| 35 to 44 | 1,511 | 1482 | 1440 | 1403 | 1353 |

| 45 to 54 | 1,683 | 1678 | 1630 | 1584 | 1541 |

| 55 to 64 | 1,577 | 1602 | 1585 | 1553 | 1528 |

| 65 to 74 | 1,101 | 1121 | 1276 | 1371 | 1363 |

| 75 and over | 1,125 | 1174 | 1255 | 1364 | 1529 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI, December 2022

Table 8: Estimated number of autistic adults in England, South East region, Surrey and local authorities, projected to 2040

| Local Authority | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| England | 396,760 | 399,579 | 409,622 | 416,848 | 417,680 |

| South East | 72,240 | 73,113 | 75,430 | 77,319 | 78,539 |

| Surrey | 9,183 | 9,246 | 9,434 | 9,585 | 9,661 |

| Elmbridge | 1,001 | 1,005 | 1,030 | 1,042 | 1,054 |

| Epsom & Ewell | 601 | 605 | 620 | 636 | 640 |

| Guildford | 1,202 | 1,208 | 1,225 | 1,239 | 1,234 |

| Mole Valley | 681 | 681 | 693 | 704 | 712 |

| Reigate & Banstead | 1,143 | 1,160 | 1,199 | 1,230 | 1,258 |

| Runnymede | 703 | 709 | 725 | 731 | 740 |

| Spelthorne | 772 | 771 | 788 | 796 | 803 |

| Surrey Heath | 689 | 692 | 698 | 703 | 706 |

| Tandridge | 677 | 684 | 701 | 719 | 725 |

| Waverley | 953 | 961 | 976 | 991 | 994 |

| Woking | 769 | 771 | 782 | 788 | 788 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI, December 2022

Table 6: Estimated number of autistic people in Surrey aged 18+ by age group and local authority, 2023

| Local Authority | 18 to 24 | 25 to 34 | 35 to 44 | 45 to 54 | 55 to 64 | 65 to 74 | 75 and over | Total |

| England | 47,206 | 76,791 | 74,764 | 71,308 | 72,586 | 54,106 | 49,371 | 46,132 |

| South East | 7,338 | 11,043 | 11,697 | 12,096 | 12,224 | 9,032 | 8,811 | 72,241 |

| Surrey | 889 | 1,297 | 1,511 | 1,683 | 1,577 | 1,101 | 1,125 | 9,183 |

| Elmbridge | 67 | 110 | 175 | 216 | 187 | 119 | 126 | 1,000 |

| Epsom & Ewell | 51 | 82 | 109 | 116 | 102 | 71 | 70 | 601 |

| Guildford | 209 | 223 | 168 | 184 | 174 | 123 | 121 | 1,202 |

| Mole Valley | 46 | 80 | 95 | 121 | 138 | 99 | 103 | 682 |

| Reigate & Banstead | 86 | 171 | 212 | 216 | 196 | 133 | 130 | 1,144 |

| Runnymede | 113 | 130 | 105 | 107 | 106 | 71 | 72 | 704 |

| Spelthorne | 65 | 112 | 137 | 138 | 134 | 92 | 92 | 770 |

| Surrey Heath | 57 | 94 | 110 | 128 | 124 | 84 | 90 | 687 |

| Tandridge | 50 | 87 | 112 | 122 | 126 | 89 | 92 | 678 |

| Waverley | 88 | 104 | 144 | 181 | 169 | 127 | 141 | 954 |

| Woking | 59 | 110 | 145 | 153 | 126 | 92 | 84 | 769 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: POPPI and PANSI, December 2022

Figure 6: Estimated number of autistic people aged 18+ by age group, living in Surrey, 2023

Source: POPPI and PANSI, December 2022

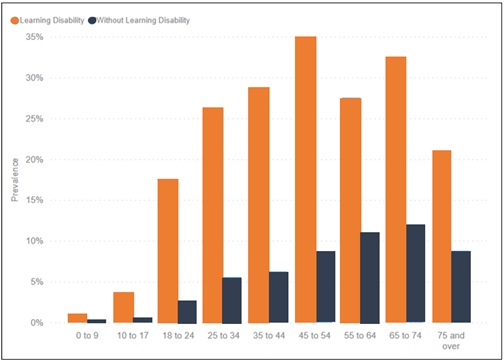

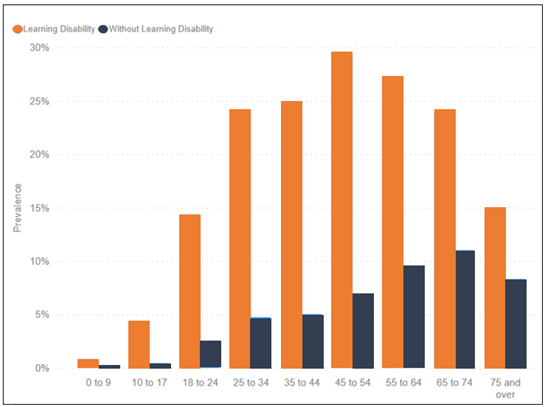

Epilepsy

The prevalence rate of epilepsy amongst people with learning disabilities is estimated to be 22%, compared to prevalence rates for the general population of 0.4% to 1%. There was no available data about the numbers of people with learning disability and those without learning disability across Surrey who have epilepsy.

However, there is data about the numbers of people with and without a learning disability who are currently on drug treatment for their epilepsy. Seizures are commonly multiple and resistant to drug treatment. Uncontrolled epilepsy can have serious negative consequences on both quality of life and the life span, although guidelines on the successful management of epilepsy in people with learning disabilities are available [9].

Table 9: Percentage of patients with an active diagnosis of epilepsy currently on drug treatment for epilepsy, as at 31 March, by year

| Year | Surrey Heartlands ICB with learning disability | Surrey Heartlands ICB without learning disability | Frimley ICB with learning disability | Frimley ICB without learning disability |

| 2016/17 | 18.1% | 0.5% | 16.3% | 0.5% |

| 2017/18 | 18.3% | 0.5% | 16.7% | 0.5% |

| 2018/19 | 18.0% | 0.5% | 16.9% | 0.5% |

| 2019/20 | 17.9% | 0.5% | 16.6% | 0.5% |

| 2020/21 | 18.0% | 0.5% | 17.4% | 0.5% |

* Patient coverage 88.0% for Surrey Heartlands ICB and 94.1% for Frimley ICB

Source: NHS Digital, Health and Care of People with Learning Disabilities, 2020/21

In Surrey Heartlands ICB, there has been little change in the percentage of the general population who have a learning disability and epilepsy and who are on drug treatment for epilepsy between 2016 and 2023. Frimley ICB shows a slight percentage increase from 2016 to 2021 but it at 17.4% remains lower than Surrey Heartlands at 18%. The data shows that a much greater percentage of epileptic people with LD need drugs to control the epilepsy than those without LD.

Learning disability and challenging behaviours

Challenging behaviours can be defined as:

‘Culturally abnormal behaviour(s) of such an intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy, or behaviour which is likely to seriously limit use of, or result in the person being denied access to, ordinary community facilities.’ [10]

‘Behaviour can be described as challenging when it is of such an intensity, frequency, or duration as to threaten the quality of life and/or the physical safety of the individual or others and it is likely to lead to responses that are restrictive, aversive or result in exclusion.’ [11]

They may also be referred to as distressed behaviour or ‘behaviours of concern’.

Using an adjusted model to predict population which considers population projections, local ethnicity and mortality rates, it is estimated that in 2023 approximately 315 adults (18 to 64 years) in Surrey will present challenging behaviour and that this number of is expected to decrease steadily to 2040. The projections from PANSI use a prevalence rate of 0.045% of the population aged 5 and over for people with a learning disability displaying challenging behaviour. (The prevalence rate is based on the study Challenging behaviours: Prevalence and Topographies, by Lowe et al, published in the Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Volume 51, in August 2007.). However, NICE guideline 2015 cite a higher prevalence quoting:

‘It is relatively common for people with a learning disability to develop behaviour that challenges, and more common for people with more severe disability. Prevalence rates are around 5 to 15% in educational, health or social care services for people with a learning disability. Rates are higher in teenagers and people in their early 20s, and in particular settings (for example, 30 to 40% in hospital settings). People with a learning disability who also have communication difficulties, autism, sensory impairments, sensory processing difficulties and physical or mental health problems (including dementia) may be more likely to develop behaviour that challenges.’ [12]

As such the projections in Tables 10 and 11 may be an underestimation and local intelligence indicates a rate more aligned with NICE guidance.

Table 10: Estimated number of people in Surrey aged 18 to 64 with challenging behaviour by age group living, projected to 2040

| Age Group | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| 18 to 24 | 39 | 40 | 45 | 45 | 42 |

| 25 to 34 | 58 | 57 | 54 | 56 | 61 |

| 35 to 44 | 70 | 69 | 66 | 64 | 61 |

| 45 to 54 | 76 | 76 | 75 | 73 | 70 |

| 55 to 64 | 72 | 73 | 72 | 70 | 70 |

| Total | 315 | 314 | 312 | 308 | 304 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: PANSI December 2022

Table 11: Estimated number of people with challenging behaviour in England, South East region, Surrey and local authorities, projected to 2040

| Area | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

| England | 15,416 | 15,473 | 15,560 | 15,618 | 15,674 |

| South East | 2,454 | 2,460 | 2,463 | 2,458 | 2,450 |

| Surrey | 315 | 314 | 312 | 308 | 304 |

| Elmbridge | 35 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 32 |

| Epsom & Ewell | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Guildford | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 41 |

| Mole Valley | 22 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 20 |

| Reigate & Banstead | 40 | 40 | 41 | 41 | 41 |

| Runnymede | 25 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 |

| Spelthorne | 27 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Surrey Heath | 23 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| Tandridge | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 22 |

| Waverley | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 29 |

| Woking | 27 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 25 |

* Figures may not sum due to rounding

Source: PANSI December 2022

Figure 7: Estimated number of people aged 18 to 64 with challenging behaviour by age group, living in Surrey, 2023

Source: PANSI December 2022

Recommendation: Given that the predicted rate is likely to be lower than the actual rate, the numbers of people presenting with challenging / distressed behaviours and behaviours of concern will need to be kept under review including via the dynamic support register.

Those who exhibit challenging behaviour are at risk of inpatient admissions. Please see the section on this later in the chapter.

Underrepresented communities and intersectionality

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) Community

As noted above, the collection of ethnic origin data across the system is poor. The 2021-2024 Surrey Heartlands Strategy includes reference to how Surrey Heartlands will reduce health inequalities faced by people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic backgrounds who have a learning disability, as highlighted in LeDeR reviews.

While the ‘GRT community’ label includes groups from a range of distinct ethnicities, they are often reported together as they believed to face similar challenges. There is data collated against the Autism Strategy which includes ‘White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller’ as a category, however this does not reflect the multiple categories newly referenced in the 2021 England and Wales census, which included more distinct group categories for the first time, including Roma. The collection of data will need to be developed for people with a learning disability and should appropriately reflect the distinctions within the GRT community. Until this time, it is important to note the census caveats of a likely substantial undercount against research statistics (drawn from bi-annual Traveller caravan count and school roll figures) [13] [14].

The Friends, Families and Travellers organisation completed research together with Amaze, an organisation which gives information, advice and support to families with disabled children and young people. Data was collected through a focus group and an online survey to discover more about awareness of learning disabilities in Gypsy and Traveller communities and to find out how community members would like to receive information on learning disabilities. Using focus groups and online surveys they found that face to face support was preferable [15].

Recommendation: Data on all underrepresented groups within Surrey will need to be gathered including the GRT community using the more distinct categories for these communities that are under development. This data can then be used to consider raising awareness and offering support to members of under-represented communities with a learning disability.

Sexual Orientation

The Mencap website states that it is important to recognise that people with a learning disability can be lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender.

People with learning disabilities experience many barriers that prevent them from expressing their sexuality and developing loving and sexual relationships, particularly if they identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) [16] [17].

The 2021 census in England and Wales is the first census that has asked people about their sexual orientation. Around 3.6 million people (7.5%) did not answer the census question. Respondents were able to select from options including heterosexual, gay, lesbian and bisexual. 2.9 million (6.0%) chose not to disclose their gender identity. 1.5% responded that their sexual orientation was gay or lesbian, 1.3% bisexual and 0.3% ‘all other sexual orientations’.

For people with a learning disability, applying the percentages above to the prevalence rate of people with learning disabilities of 21,980 in 2023 this may indicate there are potentially:

- 330 who are gay or lesbian

- 286 who are bisexual

However, given the presence of significant gaps in response (7.5% no answer, 6% not answering), these estimations should be treated with caution and further data sought as per the wider recommendation about underrepresented groups.

For people with a learning disability who are also autistic, it is worth noting that recent studies are finding that autistic individuals are less likely to identify as heterosexual and more likely to identify with a diverse range of sexual orientations than non-autistic individuals [18].

Gender Identity

The 2021 census in England and Wales is the first census that has asked people about their gender identity. Respondents were also asked whether their gender identity matched their sex registered at birth. Those who selected “no” were asked to fill in a text box describing their gender identity.

93.5% of respondents said they identified the same as their sex at birth, 0.5% said they didn’t and 6% didn’t answer.

For people with a learning disability, applying the 0.5% above to the prevalence rate of people with learning disabilities of 21,980 in 2023 this may indicate there are 110 people with a learning disability within Surrey that do not identify with the same sex at birth.

Recent research indicates that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (LGBTQ) and gender diverse adults with intellectual disability experience exclusion within disability services [19].

Recommendation: Data to be gathered within Surrey and consideration given to understanding the numbers and experiences of people with a learning disability identifying as LGBTQ+ in order to ensure barriers to expression are tackled and equity of access to services and support.

Life expectancy

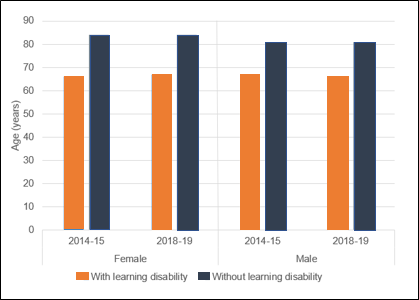

National data for life expectancy shows that in 2018/19, males with a learning disability had a life expectancy at birth of 66 years. This is 14 years lower than for males in the general population. Similarly, females with a learning disability have a life expectancy of 67 years, which is 17 years lower than for females in the general population. There has been no statistically significant change in life expectancy for people with a learning disability between 2014/15 and 2018/19 [20].

Figure 8: Life expectancy for males and females with and without a learning disability, for 2014/15 to 2018/19 – England

Source: Condition Prevalence – NHS Digital

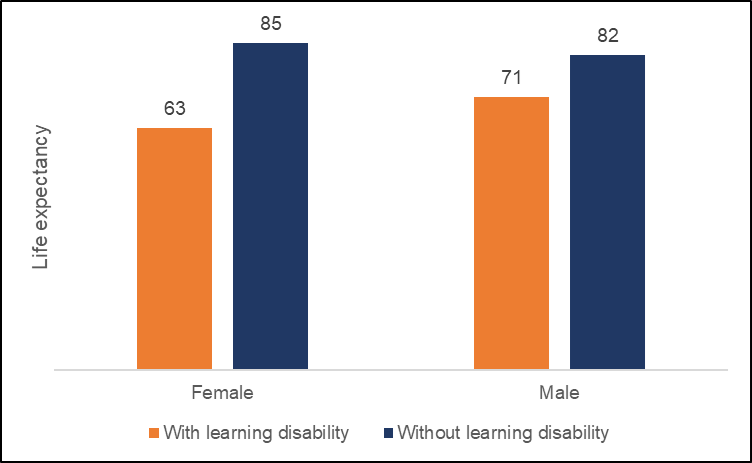

The Surrey Heartlands’ LeDeR Annual Report 2021, showed a greater disparity for females, women with learning disabilities dying 22 years sooner than the general population. For males the disparity is reduced compared with the national picture, men with learning disabilities dying 11 years sooner than the general population (Figure 9).

(The LeDeR programme (Learning from Lives and Deaths) is the national review programme which reviews the deaths of people with learning disabilities and autism across England. It started in 2018 and aims to support local areas to review the deaths of people with learning disabilities (aged four years and above) and autistic people (aged 18 years old and over), identify learning from those deaths, and ensure services are developed in order to address any learning from the review.).

Figure 9: Life expectancy in Surrey, 2020/21

Source: Surrey Heartlands LeDeR Annual Report (2020/21)

The Surrey Heartlands LeDeR Annual Report includes the deaths of children with learning disabilities. In 2020/21:

- There was a total of 2 deaths

- The range of age at death was 9 to 14

- The mean average age of death was 11.5

- The median average age was 11.5

In 2021/22

- There was a total of 3 deaths

- The range of age at death was 12 to 14

- The mean average age of death was 13

- The median average age was 13

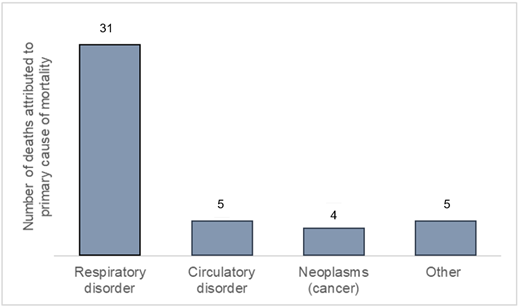

LeDeR has found that as well as dying earlier than people who don’t have learning disabilities, people with learning disabilities are three times more likely to die from an avoidable cause (University of Bristol, 2019) [21]. The 2020 national LeDeR Annual Report identifies that the four most common causes of mortality amongst people with learning disabilities are:

- Respiratory disorders

- Circulatory disorders

- Chromosomal disorders

- Neoplasms

Similarly in Surrey, people with learning disabilities die most commonly from respiratory, circulatory, and cancer-related deaths, in order of magnitude – when grouped according to these categories, the mortality profile in Surrey (Figure 10) broadly corresponds to this national picture.

Figure 10: Causes of mortality amongst people with learning disability in Surrey (2021/22)

Source: LeDeR report

The national LeDeR policy outlined local delivery expectations required from each Integrated Care System (ICS). One of these is to have a three-year LeDeR strategy demonstrating how Surrey Heartlands will act strategically to tackle the areas of health inequality experienced by people with a learning disability and autistic people. The areas of the 2021-2024 Surrey Heartlands Strategy have been identified through the thematic learning from LeDeR reviews and include reference to how Surrey Heartlands will reduce health inequalities faced by people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic backgrounds who have a learning disability. The Frimley LeDeR strategy is in draft and as such is not included.

Social care

Number of children with a learning disability open to social care

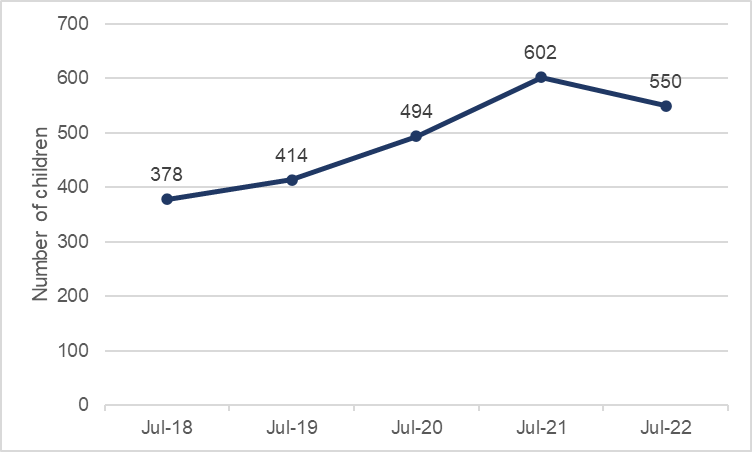

As of 24 October 2022, there were 1,376 children (under 18 years) who have an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) and social care involvement. Of these, 503 (or 36.5%) have a recorded learning disability.

The number of children who are open to social care and have a recorded learning disability as at 30 July each year from 2018 is shown in Figure 11. There has been an overall increase of 45% during this period, although the number in 2022 was a decrease from 2021. Most referrals related to Learning Disability, which covers a wide spectrum of need, are generated by schools based on their assessment of pupil’s emerging needs. There has been a corresponding increase in the number of requests for EHCP’s as a way of addressing this need. The drop in referrals in 2022 may be as a result of the 2021/2022 Academic year being affected by the period of Covid lockdown and a consequent decrease in early identification and referral but further audit activity would be required for conclusive reasons.

It is of note that disability types are rarely recorded on children’s education records, so the data is drawn from the disability type recorded on social care records, though this recording is still variable.

Figure 11: The number of children with a learning disability open to social care 2018 to 2022

Source: Surrey County Council

Surrey’s Children and Young People with Additional Needs and Disabilities Joint Strategic Needs Assessment 2022 contains significant data and insight into transitioning from being a child into an adult including the in detail in the ‘preparing for adulthood’ section (slides 115-120) and also throughout the document (Children and young people with additional needs and disabilities).

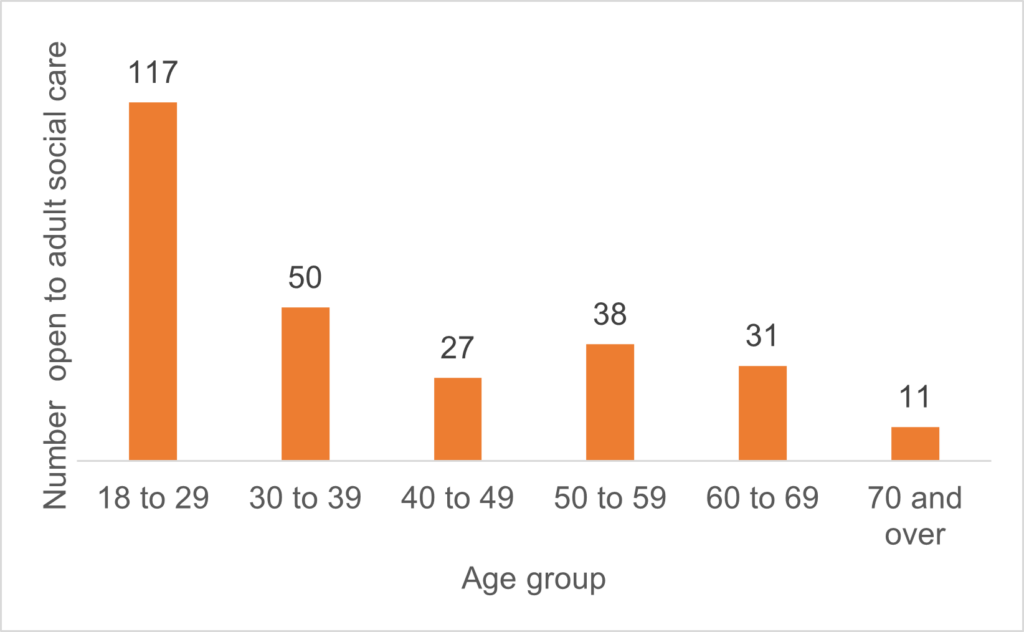

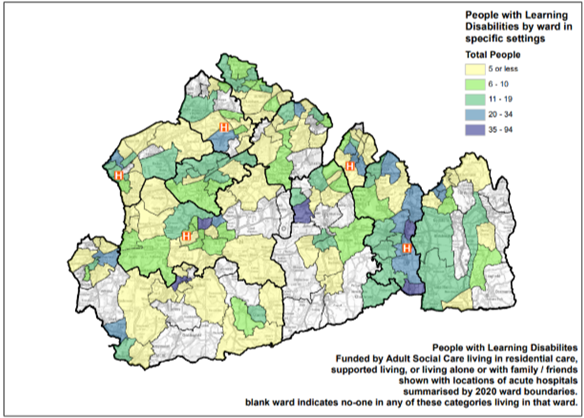

Number of adults with a learning disability open to Social Care

The number of people open to Adult Social Care (ASC) in Surrey with a Primary Support Reason (PSR) or Primary Client Category (PCC) of Learning Disability is 4,245. The Primary Support Reason is a national indicator that shows what social care an individual is provided with, while Primary Client Category is the main reason a person is known to Adult Social Care.

This includes 1,740 people who are open to Adult Social Care in Surrey identified as both having a Learning Disability and being on the Autistic Spectrum. It should be noted that although we are unable, for reporting purposes, to identify people whose primary condition is Autism.

The data is broken down into geography (district and boroughs), those living at home with family carers, age, gender and ethnicity.

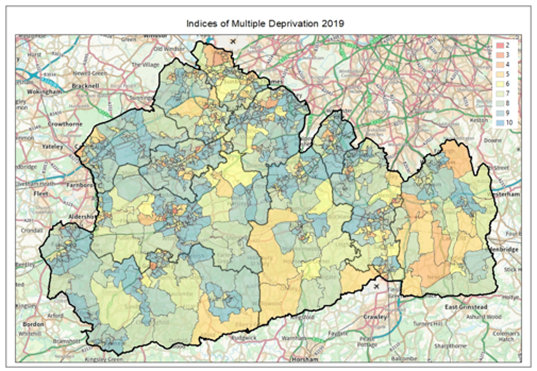

The largest proportion of people who have learning disability and/or autism (LDA) open to ASC live in Reigate and Banstead (14.7%) or are based out of county (OOC) (14.1%), where address is known. The high portion of people with a learning disability in Reigate and Banstead can be attributed to the closure of the long stay hospitals in the 1990s including Manor Park, St Ebbas and Westfield Park which resulted in a number of residential and community homes being established in the area.

Table 12: The number of people open to Adult Social Care in Surrey with a PSR or PCC of Learning Disability by District & Boroughs, excluding unknown addresses

| D&B or OOC | Count | % ASC LDA customers |

| Elmbridge | 268 | 6.4% |

| Epsom and Ewell | 239 | 5.8% |

| Guildford | 386 | 9.3% |

| Mole Valley | 295 | 7.1% |

| Reigate and Banstead | 613 | 14.7% |

| Runnymede | 232 | 5.6% |

| Spelthorne | 270 | 6.5% |

| Surrey Heath | 245 | 5.9% |

| Tandridge | 303 | 7.3% |

| Waverley | 430 | 10.3% |

| Woking | 291 | 7.0% |

| OOC | 584 | 14.1% |

| Total | 4,156 | 100.00% |

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

The number of people living at home with family carers

Adult Social Care are currently refreshing the Short Breaks offer. Data has been selected using the following criteria:

- Individuals open to ASC with a Primary Support Reason or Primary Client Category of LD, which includes people on the Autism Spectrum, regardless of whether they have a learning disability

- Accommodation Status set to ‘Settled mainstream housing with family/friends’ or ‘Living with Parents’ (excludes people with a current costed service of Residential, Nursing or Supported Living)

- Carers identified by those recorded as Main Carer

- Living in Surrey

It shows that there are 1,345 individuals over 18 years who are living at home with family carers. Of these, 268 are in East Surrey, 296 in Mid Surrey, 304 in South West Surrey and 477 in North West (October 2021).

Ethnicity

Table 13: The number of people open to Adult Social Care in Surrey with a PSR or PCC of Learning Disability by District & Boroughs (excluding unknown addresses) and by ethnicity (excluding undeclared or not known)

| D&B or OOC | Asian / Asian British | Black / African / Caribbean / Black British | Mixed / multiple ethnic groups | Other ethnic group | White |

| Elmbridge | 17 | <5 | <5 | 8 | 228 |

| Epsom and Ewell | 10 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 201 |

| Guildford | 14 | <5 | 13 | <5 | 342 |

| Mole Valley | <5 | 5 | 12 | <5 | 268 |

| Reigate and Banstead | 15 | 9 | 16 | 8 | 542 |

| Runnymede | <5 | 0 | 5 | <5 | 216 |

| Spelthorne | 16 | <5 | 6 | 7 | 230 |

| Surrey Heath | 10 | <5 | 6 | <5 | 219 |

| Tandridge | 9 | 9 | 6 | <5 | 265 |

| Waverley | 7 | <5 | 12 | <5 | 392 |

| Woking | 39 | <5 | 10 | <5 | 226 |

| OOC | 8 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 545 |

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

Table 14: The percentage of people open to Adult Social Care (ASC) in Surrey with a PSR or PCC of Learning Disability by District & Boroughs, excluding unknown addresses, by Ethnicity, excluding undeclared or not known compared with the general population (Pop) ethnicity

| D&B or OOC | Asian / Asian British (ASC) | Black / African / Caribbean / Black British (ASC) | Mixed / multiple ethnic groups (ASC) | Other ethnic group (ASC) | White (ASC) | Asian / Asian British (Pop) | Black / African / Caribbean / Black British (Pop) | Mixed / multiple ethnic groups (Pop) | Other ethnic group (Pop) | White (Pop) |

| Elmbridge | 6.7% | <0.1% | <0.1% | 3.2% | 90.1% | 6.5% | 1.2% | 4.1% | 2.0% | 86.1% |

| Epsom and Ewell | 4.3% | 3.4% | 4.3% | 2.1% | 85.9% | 11.4% | 1.9% | 4.4% | 2.8% | 79.5% |

| Guildford | 3.8% | <0.1% | 3.5% | <0.1% | 92.7% | 6.7% | 1.5% | 3.1% | 1.9% | 86.9% |

| Mole Valley | <0.1% | 1.8% | 4.2% | <0.1% | 94.0% | 3.0% | 0.8% | 2.5% | 0.9% | 92.7% |

| Reigate and Banstead | 2.5% | 1.5% | 2.7% | 1.4% | 91.9% | 7.5% | 2.9% | 3.7% | 1.4% | 84.4% |

| Runnymede | <0.1% | 0.0% | 2.3% | <0.1% | 97.7% | 9.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 83.5% |

| Spelthorne | 6.2% | <0.1% | 2.3% | 2.7% | 88.8% | 12.8% | 2.5% | 3.7% | 2.4% | 78.7% |

| Surrey Heath | 4.3% | <0.1% | 2.6% | <0.1% | 93.2% | 8.9% | 1.6% | 2.7% | 1.8% | 85.0% |

| Tandridge | 3.1% | 3.1% | 2.1% | <0.1% | 91.7% | 3.7% | 2.2% | 3.8% | 0.9% | 89.4% |

| Waverley | 1.7% | <0.1% | 2.9% | <0.1% | 95.4% | 2.8% | 0.7% | 2.2% | 0.6% | 93.7% |

| Woking | 14.2% | <0.1% | 3.6% | <0.1% | 82.2% | 14.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% | 2.1% | 78.4% |

| OOC | 1.4% | 1.9% | 2.2% | 0.9% | 93.6% | – | – | – | – | – |

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022 and Census 2021 data

The Race Equality Foundation indicated that available data does not give a definitive answer as to how many people with learning disabilities are from BAME communities which may cause difficulty in ascertaining the exact numbers of People of Colour who are reported in the statistics. [22]

According to Lancaster University’s Centre for Disability Research, between 2011 and 2020, 25% of new entrants to adult social care with learning disabilities were from minority ethnic communities. Higher rates of identification of more severe forms of intellectual disability are recorded among children of Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage. [23] [24] Below shows the percentages of individuals with an ethnicity of Asian/Asian British Pakistani or Asian/Asian British Bangladeshi open to Adult Social Care and shows percentage increases except for 2021.

Table 15: Individuals with an ethnicity of Asian/Asian British Pakistani or Asian/Asian British Bangladeshi open to ASC as a % of all individuals open to ASC with an Ethnicity of Arab, Asian/Asian British, Black/Black British and Chinese (PSR or PCC of Learning Disability and excluding unknown addresses)

| Year | % |

| 2018 | 13.3% |

| 2019 | 33.3% |

| 2020 | 52.4% |

| 2021 | 25.8% |

| 2022 | 52.4% |

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022

In Surrey between 2018 and 2022 the number of entrants of those with an ethnicity of Asian/Asian British Pakistani or Asian/Asian British Bangladeshi increased by 39.1%, with the predominant increase occurring between 2019 and 2020.

Recommendation: Seek to understand this increase, including if the higher rates of identification of more severe forms of intellectual disability are recorded among children of Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage.

Recommendation: Ensure commissioning strategies and services are able to meet cultural needs, working with the VCSE (including Surrey Minority Ethic Forum).

Age

Table 16: The number of people open to Adult Social Care in Surrey with a PSR PCC of learning disability by district and boroughs, excluding unknown addresses, by age group

| D&B or OOC | 18 to 29 | 30 to 39 | 40 to 49 | 50 to 59 | 60 to 69 | 70 and over |

| Elmbridge | 116 | 40 | 32 | 30 | 27 | 23 |

| Epsom and Ewell | 78 | 42 | 22 | 34 | 27 | 36 |

| Guildford | 167 | 78 | 43 | 53 | 29 | 16 |

| Mole Valley | 103 | 64 | 36 | 36 | 33 | 23 |

| Reigate and Banstead | 205 | 126 | 81 | 80 | 67 | 54 |

| Runnymede | 77 | 28 | 28 | 39 | 27 | 33 |

| Spelthorne | 109 | 45 | 47 | 35 | 29 | 5 |

| Surrey Heath | 85 | 67 | 21 | 31 | 25 | 16 |

| Tandridge | 105 | 57 | 31 | 57 | 34 | 19 |

| Waverley | 156 | 71 | 50 | 68 | 52 | 33 |

| Woking | 118 | 70 | 37 | 27 | 20 | 19 |

| OOC | 133 | 100 | 98 | 104 | 98 | 51 |

| Total | 1,452 | 788 | 526 | 594 | 468 | 328 |

| % | 34.94% | 18.96% | 12.66% | 14.29% | 11.26% | 7.89% |

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

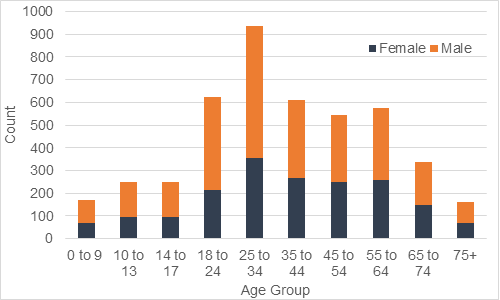

Gender

(The issues discussed in the section on ‘Gender identity’ relate.)

Consistent with the disability registers discussed above, social care data shows that there are more males than females with a learning disability. This is true in each of eleven district and borough Local Authority areas.

Table 17: The number of people open to Adult Social Care in Surrey with a PSR or PCC of Learning Disability by District & Boroughs, excluding unknown addresses, by gender

| D&B or OOC | Female | Male |

| Elmbridge | 97 | 171 |

| Epsom and Ewell | 91 | 148 |

| Guildford | 176 | 210 |

| Mole Valley | 128 | 167 |

| Reigate and Banstead | 240 | 373 |

| Runnymede | 96 | 136 |

| Spelthorne | 106 | 164 |

| Surrey Heath | 100 | 145 |

| Tandridge | 129 | 174 |

| Waverley | 184 | 246 |

| Woking | 107 | 184 |

| OOC | 226 | 358 |

| Grand Total | 1,680 | 2,476 |

| Total % | 40.42% | 59.58% |

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

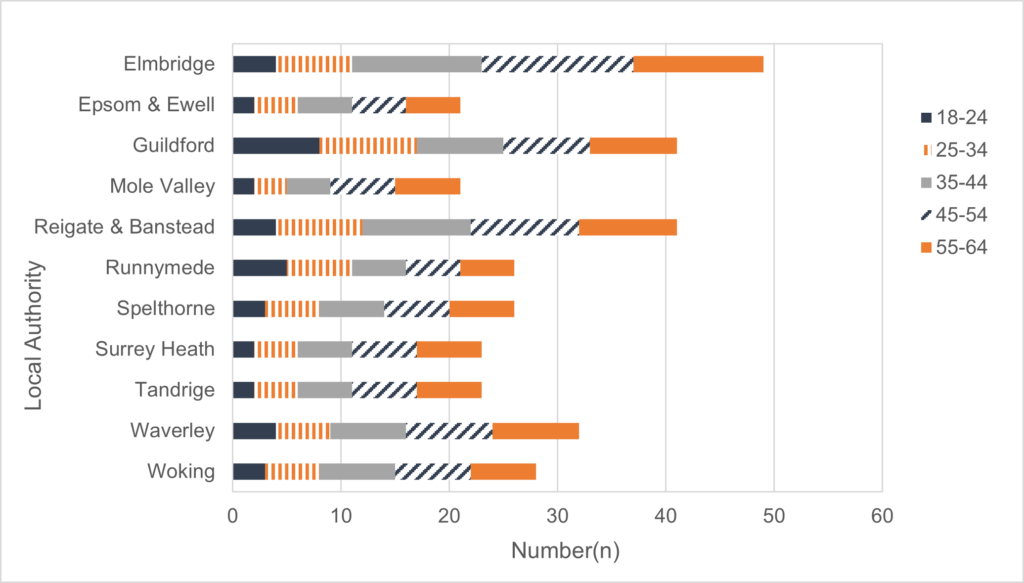

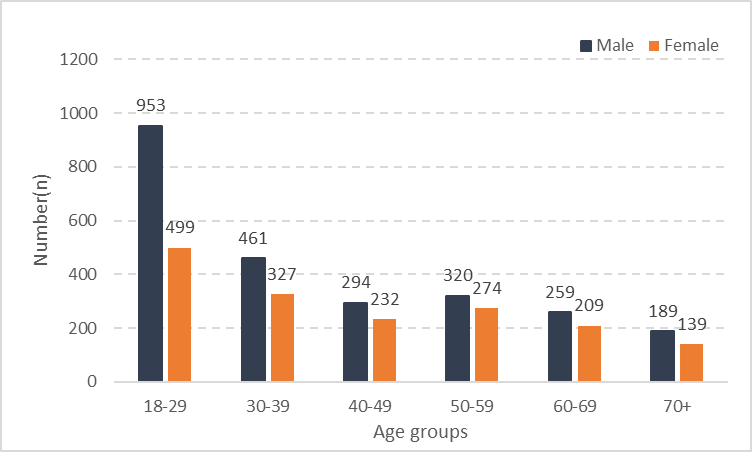

Figure 12: The number of people open to Adult Social Care in Surrey with a PSR or PCC of Learning Disability by age group and gender, excluding unknown addresses

PSR = primary care support, PCC = primary care category

Source: SCC Adult Social Care, August 2022

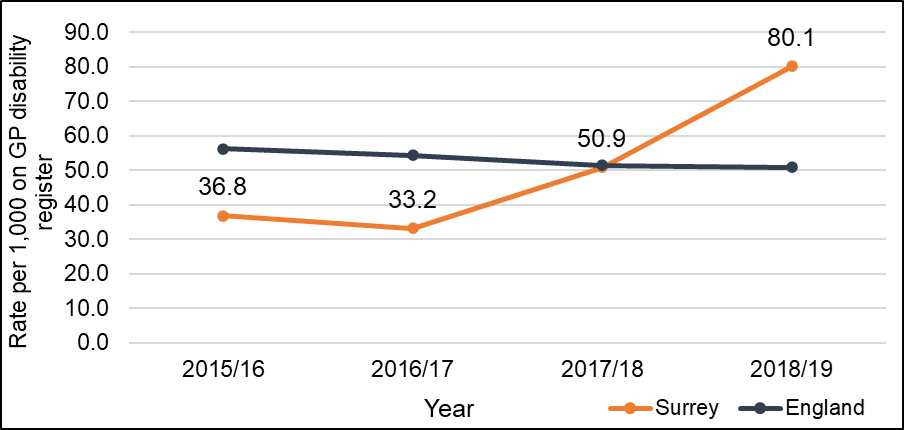

Safeguarding

Referrals to adult safeguarding have increased over time for people aged 18 and over with learning disabilities. The rate of individuals referred has gone from 36.8 per 1,000 people on the GP learning disability register in 2015/16 to 80.1 per 1,000 in 2018/19.

Figure 13: Individuals with learning disabilities involved in Section 42 safeguarding enquiries, trends over time 2015/16 to 2018/19

Source: OHID public health profiles

This increase reflects a change in policy regarding safeguarding reporting. All parties are now encouraged to report all concerns in order that they can be properly assessed, and no issue missed. Further analysis is underway to understand how the safeguarding data is used, including benchmarking and how the learning informs preventative initiatives.

Recommendation: Safeguarding data needs routinely to be benchmarked, themes from enquiries highlighted and preventative action undertaken.

Education

The number of those receiving special educational needs (SEN) support in state-funded nursery, primary, secondary and specialist schools, non- maintained specialist schools, pupil referral unit and independent schools in Surrey was 26,259 (13.0%) in 2021/22 [25]. In January 2022 there were 11,747 had an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP). [26]

Primary need

The prevalence of learning difficulties in schools will give an insight into the prevalence and the future need in the population.

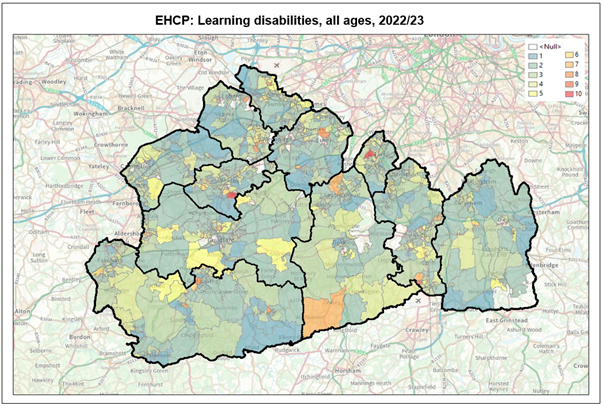

Map 1: The primary need for all pupils, all ages with a learning difficulty*, 2022/23

Source: School Census, 2022/23

Table 12 shows the primary need for SEN support is specific learning difficulty (16.8%), followed by moderate learning difficulty (14.9%).

Table 18: Primary need of pupils identified with special educational need in Surrey maintained and academies schools, learning difficulty specific, 2021

| Primary Care Need | Total Early Years (Nursery School) |

Total Primary School |

Total Secondary School |

Total Sixth Form/ College |

Total % of all needs |

| Moderate Learning Difficulty | 0 | 2,194 | 1,425 | 38 | 14.9% |

| Profound & Multiple Learning Difficulty | 0 | 17 | 214 | <5 | 1.0% |

| Severe Learning Difficulty | <5 | 38 | 287 | 89 | 1.7% |

| Specific Learning Difficulty | <5 | 1,664 | 2,413 | 37 | 16.8% |

Source: School census, 2022/2023

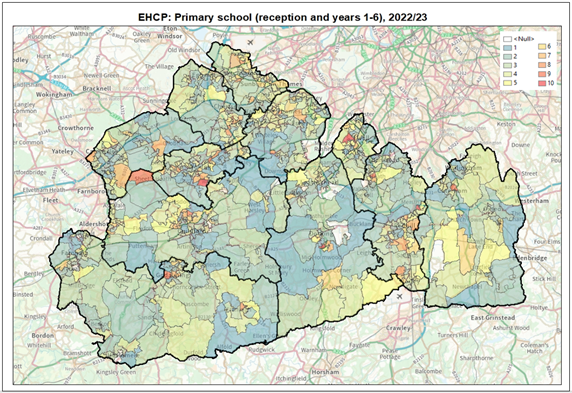

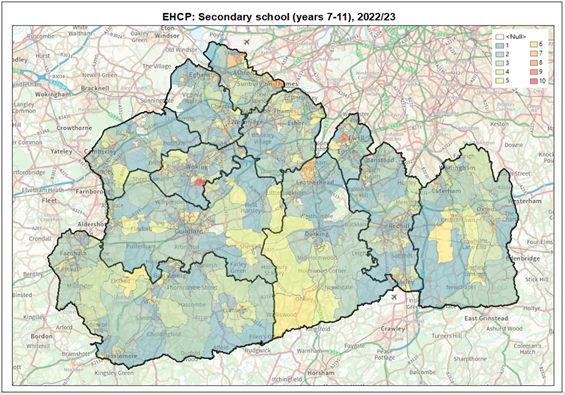

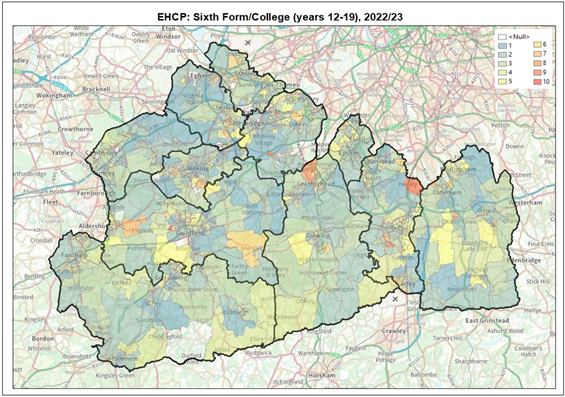

Maps 2 to 4 shows the pupil data grouped into deciles (1-10) to identify the largest population counts of primary, secondary and college/sixth form school pupils with an EHCP.

Map 2: The number of primary school children with a primary need of learning difficulty by LSOA, 2022

Source: School census, 2022/2023

Map 3: The number of secondary school children with a primary need of learning difficulty by LSOA, 2022

Source: School census, 2022/2023

Map 4: The number of sixth form or college school children with a primary need of learning difficulty by LSOA, 2022

Source: School census, 2022/2023

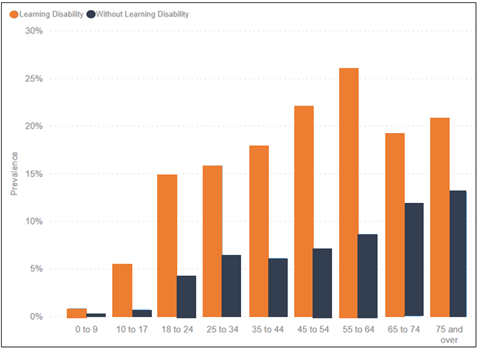

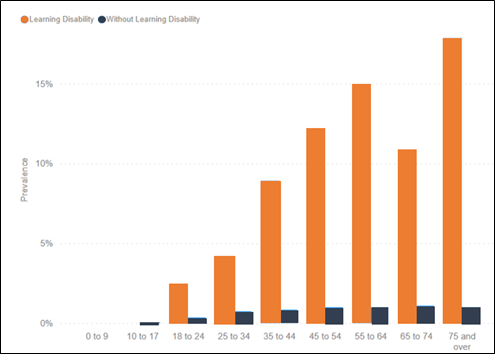

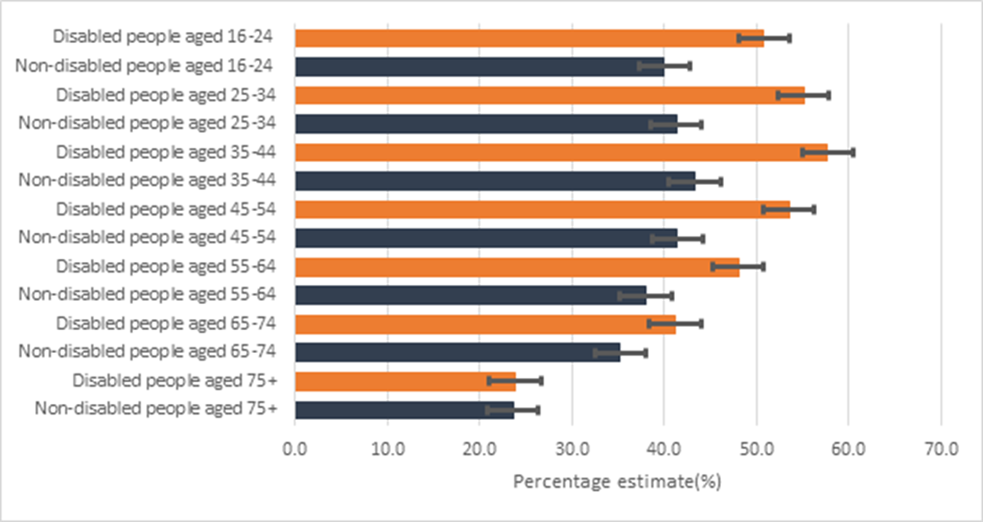

Prevalence of behaviour risk factors

The Health and well Being Strategy for Surrey includes in Priority 1 the following ambition:

‘Supporting people to lead healthy lives by preventing physical ill health and promoting physical wellbeing’

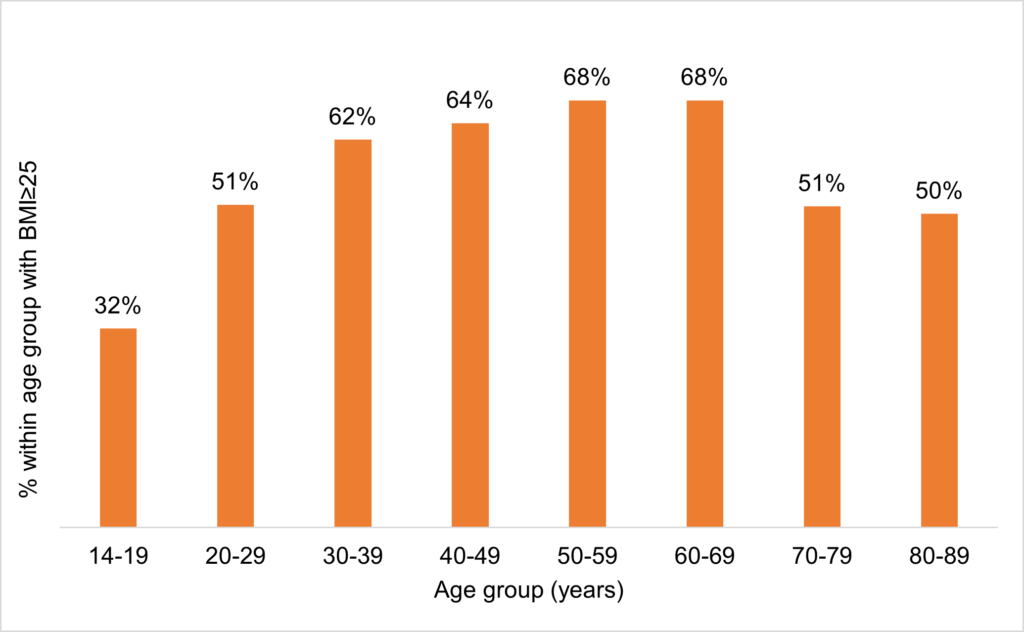

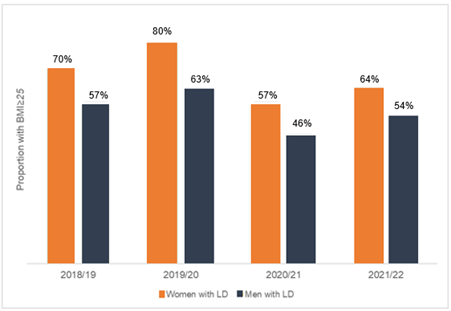

The outcomes include ‘supporting prevention and reduce substance misuse, including alcohol misuse, alcohol related harm and smoking’. Out of three behavioural markers (drug use, heavy drinking and smoking), only smoking produced significant data. (Other markers such as BMI ≥ 25, hypertension and prediabetic/diabetic blood glucose were also analysed.)

Smoking rate

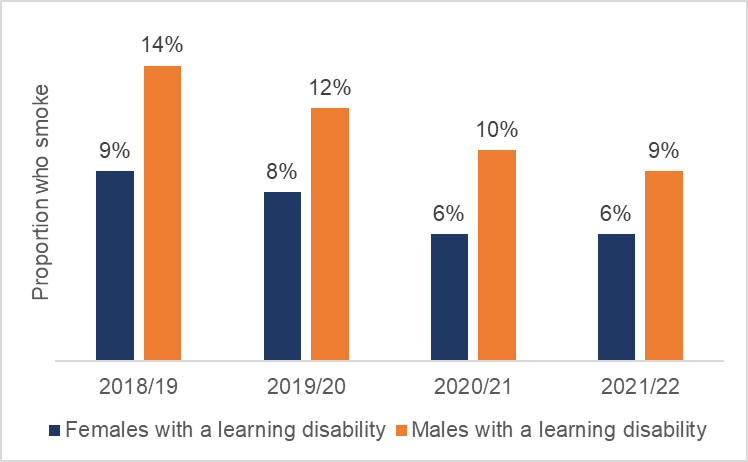

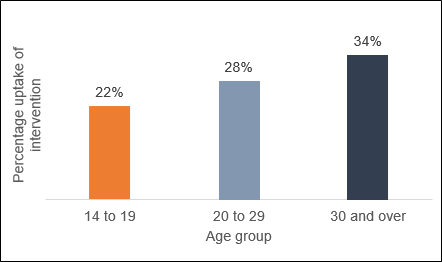

Surrey Heartlands commissioned an analysis and report (from the PSC) during 2022 to understand the health inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities (funded by Public Health in Surrey County Council). The report offered insight into the smoking behaviour of people with a learning disability on the GP register and the primary care offer in terms of lifestyle interventions using data extracted by EMIS from primary care settings across Surrey. (EMIS is the electronic patient record system used predominantly in Surrey by primary care)

Data from 2021/22 showed that men with a learning disability were 48% more likely than women with a learning disability to be smokers, and this increased likelihood is observed at a similar level in each of the three previous years also. The overall proportion of people with a learning disability on the GP register who smoked was 8% in 2021/22 the same as the previous year [27].

Figure 14: Proportion of males and females with a learning disability who smoke in Surrey, 2018/19 to 2021/22

Source: EMIS Search from Surrey GP Practice data, 2018/19 to 2021/22

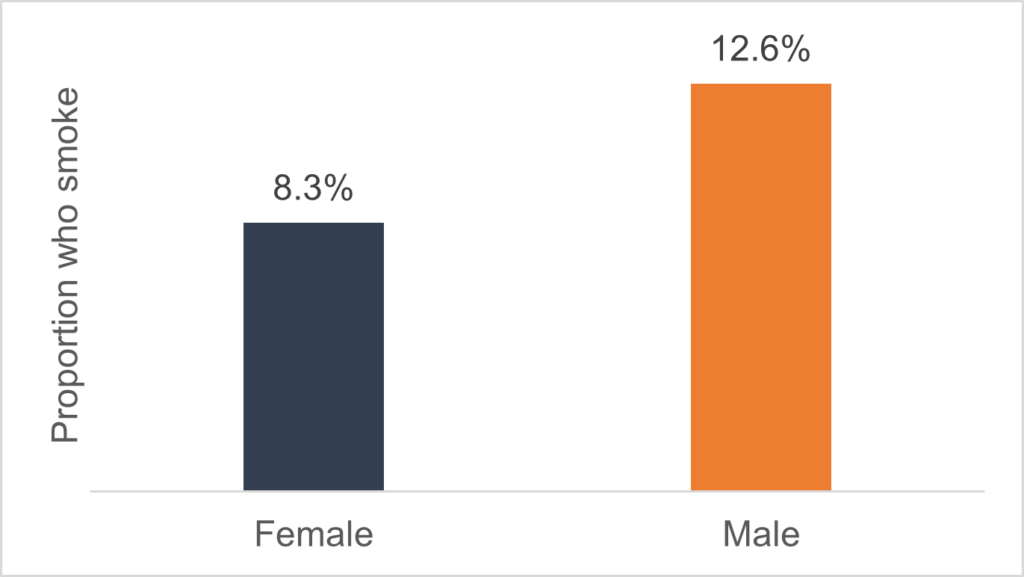

In Surrey, the prevalence of smoking in all adults aged 18 and over was 10.3% in 2020 [28], this is higher than the 8% for those with a learning disability for a similar time period (2020/21). When split by gender, the trend seen in those with learning disabilities is also seen in all adults, with males more likely to be smokers than females.

Figure 15: Prevalence of adults aged 18 and over who smoke in Surrey by gender, 2020

Source: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Tobacco Control Dashboard, 25 November 2022

Recommendation: Ensure smoking cessation support is reasonably adjusted to meet the needs of people with a learning disability and that targeted support is offered in North West place.

Advocacy support

Under the Care Act 2014, local authorities must involve people in decisions made about them and their care and support. No matter how complex a person’s needs, local authorities are required to help people express their wishes and feelings, support them in assessing their options, and assist them in making their own decisions. The advocacy duty applies from the point of first contact with the local authority and at any subsequent stage of the assessment, planning, care review, safeguarding enquiry or safeguarding adult review. Advocacy is a statutory service, that supports vulnerable people to:

- access information and services

- be involved in decisions about their lives

- explore choices and options

- defend and promote their rights and responsibilities

- speak out about issues that matter to them

Surrey County Council deliver advocacy services via two separate contracts to meet a variety of statutory legislative requirements.

- Adult Non-Instructed Advocacy

This is advocacy for adults unable to instruct an advocate as they (temporarily or permanently) lack mental capacity, subject to the Mental Capacity Act, and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS). This also applies to subjects of the Care Act 2014 who lack capacity to instruct an advocate but might not meet MCA/DoLS criteria.

This contract is a cost and volume contract spot commissioned and funded directly by the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) team on a spot commissioned case by case basis rather than block commissioned as the Adults instructed advocacy contract

This contract was newly awarded to Matrix Ltd for commencing 1st July 2022- the end of June 2025 with an option to extend by a further 24 months.

2. Instructed Advocacy

This relates to statutory advocacy for people able to instruct an advocate. The people concerned might be:

- Detained under the Mental Health in line with statutory legislation and will include those detained under Part 2 of the Mental Health Act such as those under section, guardianship, community treatment order (CTO) or Part 3 of the Mental Health Act such as those under section 37/41, 47 and 48.

- Residents of other boroughs detained in Surrey facilities under the mental health acts

- People in Prison or approved premises (in line with statutory legislation and best practice guidance and includes Care Act advocacy)

- Be entitled to advocacy under the Advocacy Care Act 2014 – for example people who have substantial difficulty understanding: (in line with statutory legislation and best practice guidance regarding Care Act advocacy, safeguarding support and young carer’s assessment and applies equally to carers in accordance with the parity they are given in the Care Act).

Care Act advocacy for young people (in line with statutory legislation and best practice) moving from Children’s to adult’s services.

Non-Statutory “Discretionary” Advocacy

The instructed advocacy contract also encompasses non-statutory/discretionary advocacy to people at risk and who require preventative support around a range of preventative issues in line with best practice such as people:

- accessing mental health/health services

- receiving substance misuse support

- living with a long-term condition or diagnosis, such as HIV

- with care and support needs who have difficulty understanding or retaining information and are at high risk of an escalation in care needs if preventative measures are not taken

This contract was newly awarded to POhWER Ltd, commencing July 2022 – June 2025 with an option to extend by a further 24 months. It is a block commissioned contract funded in partnership between:

- Surrey County Council, to meet statutory duties under the Care Act for clients with capacity to instruct an advocate

- Public Health Surrey, to provide support to people with substance misuse needs

- NWS CCG representing all CCGs in Surrey, to support engagement of people needing advocacy in health and public health settings

Out of Scope

Specifications do not encapsulate:

- Independent Health Complaints Advocacy: this is commissioned by Healthwatch Surrey and delivered by Surrey independent Living council (SILC). The contract expires in 2025/27.

- “Appropriate adults” as defined by Police and Criminal Evidence Act, 1984

- Advice and information is out of scope unless it falls within the General Care Act Duty.

- Self-Advocacy

Children’s Advocacy

The Children’s Advocacy service supports SCC to fulfil certain statutory duties detailed within the following legislation:

- Children Act 1989

- Children Leaving Care Act 2000

- Adoption and Children Act 2002

- Children and Families Act 2014

- Care Planning, Placement and Review Regulations 2010

The service follows and adheres to the broad legal frameworks of the United Nations Convention on the rights of the child and the European Court of Human Rights which promotes the rights of children and young people. The child’s right to be in heard in matters affecting them is enshrined in Article 12 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child, which also stipulates that the child shall be provided with opportunities to be heard in any judicial and administrative proceedings affecting the child, either directly, or through a representative or appropriate body. The Service Provider, in partnership with SCC, is responsible for raising awareness regarding the promotion of children’s rights.

SCC commissioned Antser Holdings Ltd to deliver Advocacy Services for up to 340 Children and Young People (see below), July 2022 – July 2025, with the option to extend for a further 12 months.

The service is monitored to ensure the delivery of high-quality, independent advocacy that enables improved outcomes for:

- Looked after children

- Children subject to child protection planning

- Care leavers up to the age of 25

- Children and young people with special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND), who have an Education Health and Care Plan (EHCP) and do not have appropriate representation

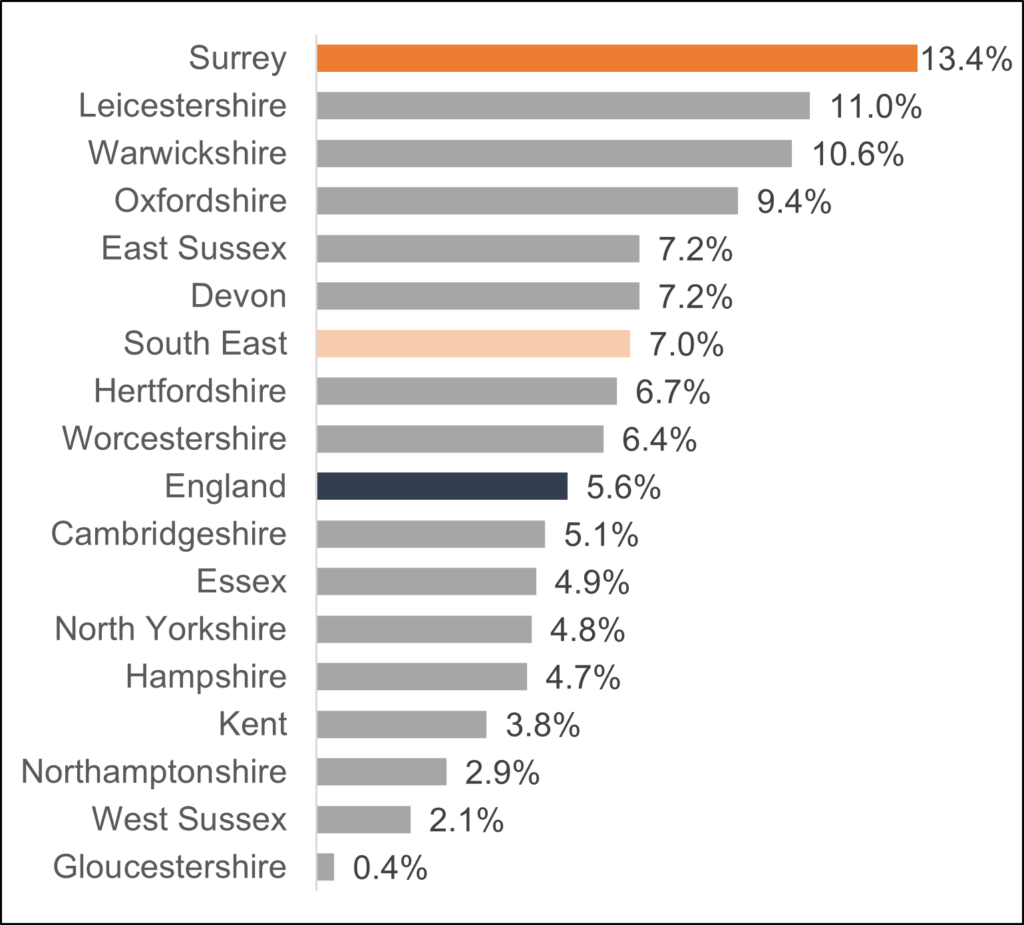

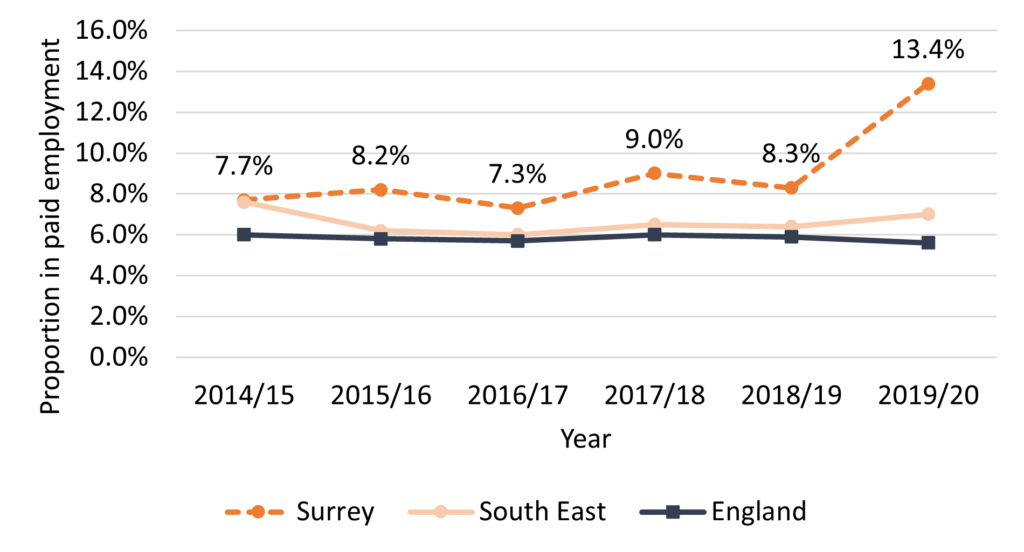

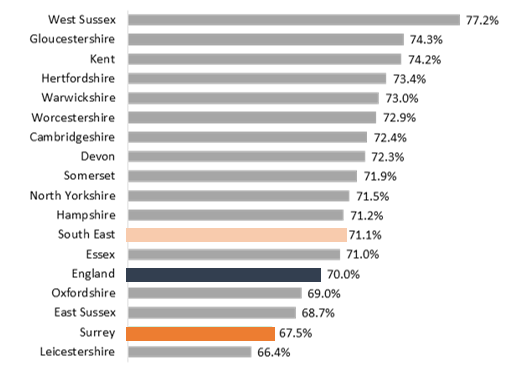

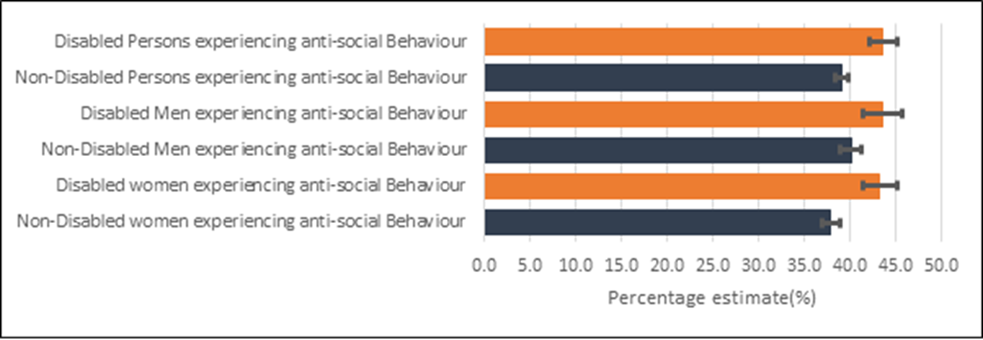

The purpose of the service is to ensure that eligible children and young people: